THANK YOU

Thank you to everyone who was able to attend our Cine-File party last Friday. We had a wonderful turnout, and it was great for all of us to meet so many of you! Thanks also to those of you who made donations online.

We’d especially like to thank Scrappers Film Group and Pentimenti Productions for hosting, and the various organizations and individuals who donated raffle items.

CRUCIAL VIEWING

Joel Potrykus’ RELAXER (New American)

Facets Cinémathèque — Check Venue website for showtimes

Reminiscent of the proto-punk plays of Alfred Jarry, Joel Potrykus’ RELAXER is a work of exhilarating contempt—the film’s assault on good taste is merely one aspect of its concentrated attack on the American success ethic. The bare-bones story, set in a single location, mocks the very concept of narrative progression, while the dialogue, which consists mainly of insults and non-sequiturs, is defiantly juvenile. (Some of the more memorable lines: “If you played tic-tac toe against yourself, do you think you’d win?” “Do you know if Chuck E. Cheese delivers?” “It smells like mouth-farts in here!”) Potrykus’ righteous anger can be felt even in his grungy mise-en-scene: RELAXER takes place in one of the dirtiest apartments you’ll ever see in a movie, and it only gets dirtier as the film begrudgingly moves forward in time, with bodily fluids, cockroaches, and a roasted bird carcass proudly staining the frames. More remarkable than the inspired gross-out humor is the writer-director’s steely formal control, as Potrykus demonstrates a meticulous sense of framing, camera movement, and pacing. (How surprising that a movie obsessed with wasting time doesn’t waste a minute itself.) He’s aided greatly by the deadpan lead performance of Joshua Burge (who previously starred in Potrykus’ APE and BUZZARD), a feat of genuine naiveté that matches the sincerity of the script and direction. Burge plays Abbie, an unemployed man who spends his days sitting around his older brother’s apartment and subjecting himself to his sibling’s abuse. The brother, Cam (David Dastmalchian), enjoys challenging Abbie to absurd dares; when the movie opens, he’s forcing Abbie to stay put on the couch until he finishes a gallon of milk in record time. Abbie fails this challenge, and so Cam browbeats him into accepting another: not leaving the couch until he reaches the fabled 257th level of Pac-Man. The game goes on and on, and the childlike hero (who refuses to accept, decades after the man’s arrest, that his estranged father is likely a pedophile) keeps his word and stays glued to couch. Nothing can get him to rise—not hunger, the presence of fumigators, or even a spectacular event that I won’t spoil here. As RELAXER evolves into a parody of survival stories, it comes to evoke another proto-punk classic, Luis Buñuel’s final Mexican masterpiece THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL. (2018, 91 min, Video Projection) BS

Shirley Clarke's ORNETTE: MADE IN AMERICA (Documentary/Music Revival)

Chicago Film Society (at the Logan Center for the Arts, 915 E. 60th St., University of Chicago) - Sunday, Noon (Free Admission)

Twenty years in the making, Shirley Clarke's final feature, ORNETTE: MADE IN AMERICA, is a riotous and impish attempt to stake out a cinematic correlative to Ornette Coleman's free jazz. ORNETTE departs from the concentrated patterns and deliberate frustrations of Clarke's THE CONNECTION and PORTRAIT OF JASON to fashion something with a thousand autonomous, moving, flashing, and flaring parts. It's analogous to the improvisatory safe havens that Coleman embedded in his Symphony No. 1, Skies of America, which forms the editorial and rhythmic backbone of the film. A proudly promiscuous film, ORNETTE explodes the documentary form by paying lip service to its conventions before scrambling them into something new. Talking head interviews are self-consciously inscribed within cartoony cathode-ray tubes and near wordless re-enactments of formative moments in Coleman's life butt up against reaction shots from latter-day on-lookers. Fragmentary film and tape footage is transformed and distorted by aggressive video effects. Fiction co-mingles with documentary, or, more precisely, biography merges with public life. There's dichotomy, but no tension, no line of demarcation. The electronic ticker outside the concert hall advertises Coleman's appearance and then slips seamlessly into presenting the film's opening credits. ORNETTE: MADE IN AMERICA is a documentary film, I guess, that also announces itself as a thing in the world. Preceded by Clarke's 1958 experimental short BRIDGES GO ROUND (two versions, 4 min each, 16mm). (1985, 85 min, 35mm) KAW

Spike Lee's DO THE RIGHT THING (American Revival)

Music Box Theatre — Check Venue website for showtimes

Spike Lee's long and prolific career has been maddeningly uneven but he is also, in the words of his idol Billy Wilder, a "good, lively filmmaker." Lee's best and liveliest film is probably his third feature, 1989's DO THE RIGHT THING, which shows racial tensions coming to a boil on the hottest day of the year in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn. Lee himself stars as Mookie, a black deliveryman working for a white-owned pizzeria in a predominantly black community. A series of minor conflicts between members of the large ensemble cast (including Danny Aiello, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Giancarlo Esposito, and John Turturro) escalates into a full-blown race riot in the film's incendiary and unforgettable climax. While the movie is extremely political, it is also, fortunately, no didactic civics lesson: Lee is able to inspire debate about hot-button issues without pushing an agenda or providing any easy answers. This admirable complexity is perhaps best exemplified by two seemingly incompatible closing-credits quotes--by Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X—about the ineffectiveness and occasional necessity of violence, respectively. It is also much to Lee's credit that, as provocative and disturbing as the film at times may be, it is also full of great humor and warmth, qualities perfectly brought out by the ebullient cast and the exuberant color cinematography of Ernest Dickerson. (1989, 111 min, 35mm) MGS

King Hu’s THE FATE OF LEE KHAN (Taiwanese/Hong Kong Revival)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Friday, 8pm, Saturday, 3pm, and Wednesday, 6pm

The third entry in King Hu’s wuxia “Inn” trilogy, THE FATE OF LEE KHAN is an assuredly feminist take on martial arts films. Set in the mid-1300s, Lee Khan (Feng Tien) and his band of Mongol warriors are traveling to receive a map of Chinese rebel forces to aide them in their goal of conquering the country. When word comes down from within their ranks that they’ll be traveling to the newly opened Spring Inn, its proprietor, Miss Wan (Li Li-hua), and her band of female resistance fighters seek to stop their Mongol foes. This narrative outline only covers one side of the film’s coin, though. There is much humor and action to be found in Miss Wan and compatriots’ (including the legendary Angela Mao) handling of unruly imbeciles that frequent the Spring Inn, assuming it to be a brothel. There is a litany of gorgeous choreography to contemplate in this nearly one-set film, and Hu builds considerable excitement in his ping-pong like editing which bounces from character to character into a cacophony of martial arts combat. The film also, at times, eschews the typical movie trope of good always triumphing over evil to strike a realistic balance when it comes to casualties. Brimming with brightness and virility, THE FATE OF LEE KHAN, at its core, relies on its terrific female leads and further cemented Hu’s status as a martial arts auteur. (1973, 105 min, DCP Digital) KC

ALSO RECOMMENDED

Giovanni Pastrone’s CABIRIA (Silent Italian Revival)

Doc Films (University of Chicago) – Friday, 7pm

What I find so exhilarating about films from cinema’s earliest days is that I can actually watch the art form being invented, now-familiar tropes appearing on screen for the first time, imaginations running wild because there were no rules. An avowed fan of sword-and-sandal epics, I was thrilled to watch CABIRIA, the progenitor of the form and of other types of film epics. Loosely based on histories written by Titus Livius in the first century BC and possibly on Emilio Salgari’s 1908 adventure novel Cartagine in Fiamme (Carthage Is Burning), Giovanni Pastrone crafted a sprawling tale of dizzying complexity. Although the film is named for a girl, Cabiria (Carolina Catena), who is separated from her family in Sicily when Mt. Etna erupts and ends up as the favorite slave of a Carthaginian noblewoman named Sophonisba (Italia Almirante-Manzini), the film mainly centers on the enmity between Carthage and Rome that ended when Rome defeated the city in the third Punic War in 146 BC. Long title cards that are more confusing than helpful try to keep the plot in line, but the reason to see this film is to gawk at the amazing set-pieces and action sequences Pastrone put on screen. He seemed very fond of fire, from the volcanic eruptions that burn Cabiria’s town and destroy her palatial home, to the grisly sacrifice of 100 children who are placed in the flaming maw of the god Moloch and the destruction of a fighting fleet that is set ablaze by a solar-heated invention of Archimede (Enrico Gemelli), who rates the only close-ups of the film. Equally impressive is a scene where Fulvius Axilla (Umberto Mozzato), the Roman hero of the story, climbs a human pyramid made up of men and shields to breach the wall of Carthage and rescue his faithful slave Maciste (Bartolomeo Pagano), who has been chained to a grindstone for 10 years following his capture; I was reminded of the scenes in another rousing epic, WONDER WOMAN (2017), in which Diana bounds into the air after boosting off from a shield. CABIRIA is noted for introducing dolly shots and for creating the character Maciste, the strongman Pagano rode to fame and fortune over the following 14 years in such films as MARVELOUS MACISTE (1915), MACISTE RESCUED FROM THE WATERS (1921), and MACISTE IN HELL (1925). Fellini was a fan of Salgari’s many adventure novels, and his admiration for CABIRIA is obvious, as he namechecks the epic with his THE NIGHTS OF CABIRIA (1957) and likely created the character of Zampanò in LA STRADA (1954) as homage to Maciste. (1914, 148 min, 16mm) MF

Steven Spielberg's JAWS (American Revival)

Music Box Theatre – Wednesday, 7pm (“drink-a-long”) and Thursday, 4:30pm*

If PSYCHO forever changed bathroom behavior, then JAWS no doubt gave us pause before diving head first into the ocean; but like the best horror movies, the film's staying power comes not from it's superficial subject matter, in this case a mammoth, man-eating shark and the ominous abyss of the deep blue sea, but from the polysemic potential and wealth of latent meanings that these enduring symbols possess. JAWS marks a watershed moment in cinema culture for a variety of reasons, not excluding the way it singlehandedly altered the Hollywood business model by becoming the then highest grossing film of all time. A byproduct of such attention has been the sustained output of scholarly criticism over the years. At the time of its release, JAWS was interpreted as a thinly veiled metaphor for the Watergate scandal (an event that was slightly more conspicuous in the book), but since then a variety of readings have emerged, including socioeconomic and feminist analyses; however, Marxist theorist Fredric Jameson may provide the most intriguing interpretation by connecting the shark to the tradition of scapegoating. Like Moby Dick or Hitchcock's titular birds, the shark functions a sacrificial animal onto which we project our own social or historical anxieties (e.g., bioterrorism, AIDS, Mitt Romney). It allows us to rationalize evil and then fool ourselves into thinking we've vanquished it. But by turning man-made problems into natural ones we forget that human nature itself is corrupt, exemplified here by Mayor Vaughn who places the entire population of Amity Island in peril by denying the existence of the shark. Jameson's reading is in keeping with the way in which Spielberg rarely displays the shark itself (the result of constant mechanical malfunctions); as opposed to terrifying close-ups, we get point of view shots that create an abstract feeling of fear, thus evoking an applicable horror film trope: the idea is much more frightening than the image. JAWS is a timeless cautionary tale because it appeals to the deep-rooted fears of any generation. (1975, 124 min, 35mm) HS

---

The Wednesday screening is an interactive “drink-a-long” show and the Thursday screening is a proper showing of the film.

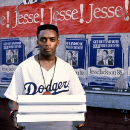

John Singleton’s BOYZ N THE HOOD (American Revival)

Music Box Theatre — Friday and Saturday, Midnight

Orson Welles was just 25 years old when he made CITIZEN KANE, but John Singleton has him beat by two years, having been only 23 when he wrote and directed BOYZ N THE HOOD, a staggering feat that’s intensely personal and distinctly relatable—personal not just for him but also many of his viewers, who very rarely, if at all, saw their truth projected 24 times a second on the big screen. Set largely in South Central Los Angeles, the film has two parts: the first , in 1984 (the first iteration of the script was titled “Summer of 84”), depicts the protagonists as young boys, and the second, in 1991, with said boys all grown up and on their respective paths. Cuba Gooding, Jr. stars as the adult Tre Styles, who was sent by his mother (Reva, played by the one-and-only Angela Bassett) to live in South Central with his father, Furious (Laurence Fishburne, dispensing wisdom like Morpheus but ever so sensitively), where he falls in with a group of local pre-teens, among them “good kid” Ricky (played as an adult by Morris Chestnut) and his brother Doughboy (played as an adult by Ice Cube, in a remarkably devastating performance). The film switches to 1991 after a series of scenes in which Tre spends time with his father and Doughboy is arrested for stealing, a dichotomy that permeates the rest of the film, as is evidenced by the 1991 portion opening with Doughboy’s return home from jail for yet another offense. The rest of the film follows the boys—now young men—over an ambiguous period of time leading up to their college acceptance, with Tre and Ricky headed for university (the latter due to his capabilities on the football field) and Doughboy not. As in real life, the events leading up to the tragic ending don’t seem especially significant: Tre hounds his girlfriend, Brandi (Nia Long) for sex, and Ricky, already with a kid of his own and having been scouted by the University of Southern California, attempts to get higher than a 700 on the SAT so that he can play college ball. Things come to a head when Ricky gets into a skirmish with some local gang members, who later seek revenge. Unlike CITIZEN KANE, it’s not a whole lifetime that Singleton depicts, but rather the events that define a lifetime, a phenomenon of perspective that seems to affect people like those in BOYZ N THE HOOD more than it does rich, white men like Charles Foster Kane. Singleton began working on the film while at USC; it's based on his life and those of people he knew. It was also inspired by François Truffaut's THE 400 BLOWS—Singleton and Truffaut share surprising similarities in their handling of troubled youth. For his extraordinary effort, Singleton was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Director, becoming not only the youngest person ever nominated, but also the first African American, almost twenty years before Lee Daniels for PRECIOUS. Singleton passed away in April at the age of 51—gone before his time, but having left a body of work that will persist even after his death. (1991, 112 min, DCP Digital) KS

Marcus Lindeen’s THE RAFT (New Documentary)

Gene Siskel Film Center — Check Venue website for showtimes

I’ll confess to being skeptical about THE RAFT, which, much like the cuckoo 1973 social experiment it details, at first seems like something centered on sex and violence. Marcus Lindeen’s documentary, however, reveals itself to be a more nuanced expedition—pun intended—into the mystifying terrain that is human nature. The experiment in question was devised by Mexican anthropologist Santiago Genoves, who was inspired after having been a passenger on a hijacked plane. With that in mind, he designed an experiment where 11 people from different backgrounds would sail across the Atlantic on a relatively primitive raft, called the Acali but sometimes referred to as the "sex raft," with the intention of fostering an intimate—and dangerous—environment in which violence and sexual tension would thrive. The film is an interesting mix of archival footage from the voyage, with Genoves’ observations read in voiceover, and stylized interviews with those of the group who are still alive (seven remain—six women and one man) on a replica of the raft. Perhaps most revelatory about the Acali Experiment are the women, who continue to prove themselves as the true leaders of the expedition. (In all fairness to Genoves, he intentionally put women in positions of power but betrayed his own aims by later undermining them.) The film's pacing lends itself to this more subtextual reading but also betrays its entertainment value at times—to be frank, a subject this expansive, one rife with both high drama and meaningful insight, may have worked better as a television series. (2018, 97 min, DCP Digital) KS

Fritz Lang's METROPOLIS (Restored Version)

Music Box Theatre - Sunday, 7pm

The now-famous story of METROPOLIS' new restoration—nearly half an hour of footage recovered from a newly-discovered 16mm print that had been sitting in Argentina since 1928, comprising a more or less definitive version only a few minutes shorter than the premiere print—has eclipsed just exactly what those restored 25 minutes do to this Introduction to Film History juggernaut/music video reference-point, a delirious fantasy that's had the unfortunate fate of being boiled down to its "iconic moments," muddled politics (courtesy of an ostensibly "socialist" script by future Nazi Thea von Harbou) and its status as the only Fritz Lang movie to not have any real people in it (besides, of course, villain Rotwang). If previous versions (most notably the enthrallingly ridiculous one produced by Giorgio Moroder, which runs half the length of this one) made METROPOLIS seem more like a von Harbou film than a Lang one, the now "complete" version of this sprawling future fever-dream actually resembles a movie someone as smart as dear old Fritz would make. More nuanced because it is more excessive, the restored METROPOLIS is a film that understands (and feels through) its artificiality—as well as the fixations with death and female sexuality inherent in its material—instead of presenting it as straight allegory; it's fitting that the first piece of restored footage, arriving about seven minutes in, is a brief sequence of a man applying make-up to a woman. Since METROPOLIS tells its story (about a 21st century city made possible by a caste of underground-dwelling workers) through two substitutions—the son of the city's ruler taking the place of a worker; a vicious cyborg taking the place of a saintly young woman—previous versions have inevitably picked the son (Gustav Fröhlich) over the worker (Erwin Biswanger), and the cyborg over the girl (both played by Brigitte Helm; in this case it's understandable, because she is more interesting playing a villain). This version restores the ample screen time devoted to 11811, the prole who trades places with heir apparent/smirking naïf Freder, and to 11811's adventures in upper-class decadence (especially in a scene that now seems essential—a car filling up with flyers for a local night club, dissolving into a montage of excesses), as well as many apocalyptic hallucinations and black-gloved intrigues (especially so in the case of striking Lang regular Fritz Rasp; essentially an extra in previous versions, this cut presents him as a major character in both the realities of the plot and in Freder's nightmares). With an original live score performed by David DiDonato. (1926, 148 min, DCP Digital) IV

MORE SCREENINGS AND EVENTS

The Chicago Film Society (at Northeastern Illinois University, The Auditorium, Building E, 3701 W. Bryn Mawr Ave.) screens Doris Wishman's 1961 nudist film NUDE ON THE MOON (83 min, 35mm) on Wednesday at 7:30pm. Preceded by George Kuchar's 1966 experimental short HOLD ME WHILE I'M NAKED (17 min, 16mm).

Comfort Film at Comfort Station Logan Square (2579 N. Milwaukee Ave.) presents Church Basement Cinema Presents: Quadrus Films on Tuesday at 8pm. This program of a short and a featurette produced for the church/religious market includes: Bruce Lood's THE GREAT BANANA PIE CAPER (1978, 28 min, 16mm) and John L. Pudaite's CHOICES (1988, 55 min, 16mm). Free admission.

Chicago Filmmakers (5720 N. Ridge Ave.) screens Michael Stock's 1993 German film PRINCE IN HELL (89 min, Digital Projection) on Friday at 7pm; and Vlada Knowlton's 2018 documentary THE MOST DANGEROUS YEAR (90 min, Digital Projection) on Saturday at 7pm.

Also at the Gene Siskel Film Center this week: Denis Do’s 2018 French/Luxembourgian/Belgian animated film FUNAN (84 min, DCP Digital) plays for a week; Francesco Rosi’s 1979 Italian film CHRIST STOPPED AT EBOLI (223 min uncut version, DCP Digital) is on Friday at 2pm, Saturday at 7pm, Sunday at 2pm, and Thursday at 2pm; Jiri Vejdelek’s 2018 Czech Republic film PATRIMONY (90 min, DCP Digital) is on Friday at 6pm and Monday at 8pm; David Ondricek’s 2018 Czech Republic film DUKLA 61 (150 min, DCP Digital) is on Saturday at 5pm and Tuesday at 6pm, with actress Antonie Formanová in persona at the Tuesday show; and Jack Hazan’s 1973 UK documentary A BIGGER SPLASH (105 min, DCP Digital) is on Saturday at 8pm, Monday at 6pm, and Wednesday at 8pm.

Also at Doc Films (University of Chicago) this week: David Lynch's 1990 film WILD AT HEART (125 min, 35mm) is on Saturday at 7 and 9:30pm.

Also at the Music Box Theatre this week: Sheena M. Joyce and Don Argott's 2019 documentary FRAMING JOHN DELOREAN (109 min, DCP Digital) opens, with producer Tamir Ardo in person at the Saturday show; Thomas Stuber's 2018 German film IN THE AISLES (125 min, DCP Digital) and Andrew Slater's 2018 documentary ECHO IN THE CANYON (90 min, DCP Digital) both continue; and Carolina Hellsgård's 2018 German film EVER AFTER (90 min, DCP Digital) is on Friday and Saturday at Midnight.

The Cultural Service at the Consulate General of France in Chicago hosts an outdoor screening of Jean-Luc Godard's 1960 French film BREATHLESS (90 min, Video Projection) on Saturday at 8:30pm at Belmont Harbor Park (3600 N. Recreation Dr.). Free admission.

The Millennium Park Summer Film Series (at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion) presents an outdoor screening of Sidney Lumet's 1978 film THE WIZ (136 min) on Tuesday at 6:30pm. Free admission.

ONGOING FILM/VIDEO INSTALLATIONS

Local videomaker, artist, writer, activist, and educator Gregg Bordowitz is featured in a career retrospective exhibition, I Wanna Be Well, at the Art Institute of Chicago through July 14.

Also on view at the Art Institute of Chicago: Martine Syms' SHE MAD: LAUGHING GAS (2018, 7 min, four-channel digital video installation with sound, wall painting, laser-cut acrylic, artist’s clothes).

CINE-LIST: June 28 - July 4, 2019

MANAGING EDITOR // Patrick Friel

ASSOCIATE EDITORS // Ben Sachs, Kathleen Sachs, Kyle A. Westphal

CONTRIBUTORS // Kyle Cubr, Marilyn Ferdinand, Harrison Sherrod, Michael G. Smith, Ignatiy Vishnevetsky