Cine-File continues to cover streaming and other online offerings during this time of covidity.

ONION CITY EXPERIMENTAL FILM + VIDEO FESTIVAL

The Onion City Experimental Film + Video Festival, originally scheduled to take place in March, continues in an online version through June 28. Programs will be rolled out over two long weekends, June 18-21 and June 25-28, and each will be available for viewing for several days. Visit the Onion City website for the full schedule and for information about online Q&A sessions. Check back here next week for additional reviews of select programs.

Are We There Yet?

Available for free viewing from 6/19 at 5pm to 6/24 at midnight here

Are We There Yet?, the title of the knockout first shorts program in this year’s Onion City Film Festival, suggests distances and deferrals, but the thread that emerges between these eight short films has more to do with the domestic, the local, and the immediate. The first work on the program, Lilli Carré’s PRIVATE PROPERTY, is downright claustrophobic, crafting a bedroom topography through series of elegant spatial mutations. Billed as a “forensic study,” the piece shuffles through sketches of deceptively anodyne interiors, but close attention reveals unmistakable signs of domestic distress—a door chain lock suddenly tautening, a mouse hole growing unsettlingly large. Carré proposes a parallel between the animator’s ability to distort space and the way that the contours of our dwellings become externalizations of emotional states. In several of the films to follow, cinema appears as a tool for folding space, and for apprehending the forces, both visible and invisible, that shape these environments. Molly Pattison and Andrew Wood’s SHOOT-THE-CHUTES is an amusement park tour that intriguingly combines candy-hued 16mm aesthetics with analytical overtures, suggesting a situationist essay film derailed by a sugar high; Caitlin Ryan’s S P A C E L A N D similarly juggles modes, its sober film footage of storage spaces sandwiched puckishly between digital effects, George Carlin quotes, magic tricks, and scripted sequences. Both render space as a function of the tension between impulsivity and control. Another fascinating (and painfully timely) dialectic emerges between Ben Balcom’s GARDEN CITY BEAUTIFUL and Zach Epcar’s BILLY, both exceptional. The former, an extension of the Milwaukee psychogeography Balcom ventured in SPECULATIONS (2016), betrays the assurance of a filmmaker whose technical grasp is matched by his deep investment in the community he inhabits. Balcom’s camera limns the contours of freeway interchanges, encountering odd outcroppings of concrete in the negative spaces between residential sidewalks; an inspired series of zoom-outs transform dull striations of asphalt into yawning vortices. Two onscreen surrogates (Rudy Medina and Alyx Christensen) narrate dreams of the city as a shaky utopia, drawn from the conjectures of turn-of-the-20th-century Milwaukee socialist Victor Berger. Between these lines, an emancipatory yearning surfaces, one whose roots lie in the material history of the city’s infrastructure, the elastic reality of its public space, and the enduring aspiration towards mutual prosperity enacted in friendship and collaboration. Epcar’s BILLY, conversely, conjures a cataclysm of isolation. After a sleeper awakens from a vivid nightmare, the chirp of a barcode scanner announces an Amazon delivery, and the possibility of a rupture in the rigidly-enforced boundaries of the suburban home. Epcar shares Carré’s gifts for cultivating transient atmospheres of dread from domesticity, forging subliminal linkages through deft, faintly Bressonian pleats of self-shot and appropriated material. An emphatic and increasingly impressive stylist, Epcar’s images exude artifice: like Todd Haynes’s SAFE, deliberate framing, uncanny lighting, and stilted performances here cultivate an atmosphere of repression permeated by doubt. If Balcom’s film gestures towards the vanishing socialist dream of interdependence, BILLY augurs an era of social distancing, defined by the menace of the unseen intruder and its convenient doppelganger, the delivery guy: a world under self-quarantine. Are we there yet? Also on the program: Michael Wawzenek's STRESS BALL, Kenny Reed and Ben Popp's GOD DOG, and Alee Peoples’ STANDING FORWARD FULL. (approx 60 min total) MM

Immaterial Girls

Available for free viewing from 6/20 at 5pm to 6/24 at midnight here

I’m struck by the continuities to be found among the videos in Immaterial Girls, the second program in this year’s Onion City Experimental Film + Video Film Festival. Some should be immediately obvious: all seven works are by women, femmes, and non-binary makers, and all engage aesthetics of glitch and image manipulation to different ends. Formal resonances abound, and the recurrence of images of sexual violence serves as an unmistakable reminder of the dismal continuity of abuse under patriarchy. Ariel Kate Teal’s ROMANTIC GETAWAY and Jessica Bardsley’s GOODBYE, THELMA offer the most striking matched pair: both push borrowed pop-culture material to the brink of visual abstraction as they narrate traumatic memories and fears. ROMANTICde GETAWAY couches Teal’s personal recollections within TV tropes, through invocations of “earlier seasons” and “special episodes” and heavily cropped and zoomed imagery from 90s shows. These allusions promise a merciful distance, but their palpable incongruity only heightens the painful impact of the narrative, told entirely through on-screen text. Teal’s voice is uncompromisingly personal and their use of language extremely precise, particularly in their modulation of first- and second-person address, which often elides the distinction between the viewer and the abuser through the single pronoun you. In its direct implication of the viewer, ROMANTIC GETAWAY forecloses on the possibility of a neutral position in the face of sexual violence, frustrating any temptation towards either exculpation or catharsis. Yet its images, which gradually fade into pure color, also confound our demand for legibility; ultimately, Teal powerfully claims their right to speak directly and obliquely at the same time. Bardsley’s GOODBYE, THELMA also exploits the ambiguity of onscreen text to great effect. Shown in a white, inverted monochrome, scenes from THELMA & LOUISE appear between text cards that recount the filmmaker’s sometimes fearful encounters while traveling alone in spaces of nature. Like Teal, Bardsley transforms her source material into a blank canvas, imposing gaps and silences that can swell with dread, but which nonetheless promise potential transcendence. “Sometimes I think fear is a fantasy, a mirror, a horror film of my own creation,” the piece proposes, “and other times I think it’s a form of intelligence.” Another pair of works in the program explicitly invoke horror films as cloudy, glitch-smeared mirrors of female victimhood and empowerment. The first, Victoria Vanderpool’s SHE CAN RUN, SHE CAN HIDE, contorts the iconography of the Final Girl through blurry analog video and image synthesizers. As the image degrades, so too does the psyche of the onscreen text’s “narrator,” whose exposure to the Madonna remake of SWEPT AWAY triggers increasingly alarming thoughts and fantasies. “Real life, the worst movie I have ever seen. Would I die in the movie?” The question verbalizes one of the program’s most important continuities, that between pop-cultural images of female victimhood and real-world violence; by that same token, Ariella Tai’s CAVITY summons textual icons of Black female monstrosity (ALIEN, QUEEN OF THE DAMNED, a sword-wielding Whitney Houston in THE BODYGUARD) as figures of agency in a new, alternate reality. Imbued with their power, Tai scrambles and circuit-bends the image track, manifesting abjection as a force of creative malevolence in the ageless tradition of witchcraft. Appropriation, manipulation, verbalization, incantation: these works demonstrate the undiminished vitality of feminist strategies pioneered decades, if not centuries, in the past. Jesse McLean’s CURIOUS FANTASIES, for instance, colorfully muses on the visual and verbal construction of consumer femininity through perfume advertising, echoing 1970s semiotic media critiques like KILLING US SOFTLY through post-internet practices of digital détournage. In terms of form, it’s the kind of endurance I’m heartened to encounter, especially in an experimental film festival with over thirty years of history. But as long as gender remains a tool of oppression in a society bent on reproducing inequality, I suppose continuity isn’t necessarily a cause for celebration. Also on the program: Rebba Amaris’s IR(REGULAR) MEMORY and Lydia Moyer’s THE FORCING (EPILOGUE). (approx 53 min total) MM

Re: Re: Re: Remembering

Available for free viewing from 6/21 at noon to 6/24 at midnight here

This eclectic screening rotates around memory and hauntings. Cinematic hauntings from Shelly Silver's TURN (2018) which reimagines the final frames of Godard's "Breathless" with the filmmakers' friends and acquaintances reversing the gaze and action in a clever and jaunty bit of reclamation. Aaron Zeghers's MEMOIRS (2019) is hand-sewn domestic document with familial voices telling tales over alternating images of

comforting domesticity and quaking and chemically altered portraiture. Adrian Garcia Gomez's ASCENSOR (2019) combines stark, stuttering religious and natural iconography in "an exploration of grief, longing, and mysticism through a queer lens." Andrés Solis Barrios' LA AGUJA Y EL TAMBOR (2020) heightens the grainy depths of home movies and fabrics and flowers in a lovely elegy. Pegah Pasalar's LOST IN HER HAIR (MONDAY) (2019) is a sharp and angular time-jumping self-portraiture considering the cracks that show over space and time. Lynne Sachs's A MONTH IN SINGLE FRAMES (2019) is one of a trio of films created with images created by the late and great Barbara Hammer that she handed off to trusted friends to finish after she knew her time was drawing near. The images are from a seaside residency, and Sachs has done a beautiful job of imparting a graceful and light touch, playing harmoniously with the characteristic force of Hammer's voice. (approx 58 min total) JBM

Photographs of the Future

Available for free viewing from 6/25 at 5pm to 7/1 at midnight here

The four shorts in this topical program explore issues of race, poverty, and political action. The first two works are by American filmmakers and the second two are by British filmmakers, but their concerns overlap. Mitch McCabe’s CIVIL WAR SURVEILLANCE POEMS (PART 1) delivers sharp insights into what it means to be poor in the United States today. In the most affecting passages, McCabe cuts from one shot of American interstate to another (all taken from moving cars) while playing audio of people calling into talk radio shows to discuss their financial problems. The road, like the cycle of poverty, seems endless. McCabe also incorporates interviews with strippers, deglamorizing their work by focusing solely on the economics of what they do; this furthers McCabe’s theme of poverty being all-consuming. The filmmaker describes CIVIL WAR SURVEILLANCE POEMS as speculative fiction made 16 years in the future, after “a protracted [American] civil war: “The project is partly nostalgic political travelogue, partly a quest to mine the archive for what went wrong, and part prewar surveillance records,” McCabe writes. That’s a fascinating conceit, though the movie works perfectly well as a present-tense consideration of what’s going wrong in America now. In contrast, Ashley Teamer’s 3 PART HORROR-MON-EE is concerned with the legacy of past events. Teamer structures this montage-based work around audio of police scanners and ominous weather forecasts, creating the sense that New Orleans is bracing for perpetual calamity. She also crafts some wonderful, poetic passages, such as superimpositions of basketball players over views of a cityscape from an airplane window. The mélange of sounds and images speak to the conflicting feelings of wonder and terror with which Teamer characterizes her upbringing in post-Katrina New Orleans. Images of clouds return in British filmmaker Ufuoma Essi’s ALL THAT YOU CAN’T LEAVE BEHIND, but this time in concert with shots of people dancing. The combination is fitting, as the work is lively and lyrical on the whole. Comprised mainly of pre-existing footage, BEHIND is bookended with interviews with Nina Simone about freedom and her sense of social responsibility as a Black artist. In between, Essi combines scenes of a jazz performance (which includes a rousing drum solo), a parade, a basketball game, and a successful performance by a rodeo cowboy. Everyone onscreen is Black, which speaks to the range of contributions that Black people have made to Anglo-American society. SOUTH, by British writer and artist Morgan Quaintance, continues this theme, considering similarities between civil rights demonstrations in Chicago in 1968 and anti-apartheid demonstrations in London in 1986. Quaintance situates both cities historically and geographically, bringing in personal narratives as well; one personal digression (which I won’t spoil here) closes the film, and the content is so unlike what’s come before that its inclusion seems like an enigma. The montage is sweeping, bringing together a trove of detail about personal lives and public movements. How appropriate that a movie about making history should feel like a history in miniature. (approx 67 min total) BS

LOCAL ONLINE SCREENINGS – New Reviews

Peter Sellers’ MR. TOPAZE (UK)

Available to rent through the Music Box Theatre here and Gene Siskel Film Center here

Albert Topaze (Peter Sellers) is a humble, scrupulously honest teacher in a second-rate private school for boys in provincial France. He is a patsy for the attractive daughter (Billy Whitelaw) of the school’s owner (Leo McKern) who cajoles him into correcting homework for her as he implores his fellow teacher and friend (Michael Gough) to help him win her hand in marriage. Unfortunately, Topaze sticks to his principles when a baroness (Martita Hunt) wants him to change her grandson’s report card and ends up unemployed. It is then that he is recruited into running a shell company for the corrupt lover (Herbert Lom) of a stage performer (Nadia Gray). What will become of Topaze and his high moral principles? Based on a play by Marcel Pagnol, the first filmmaker elected to the Académie française, MR. TOPAZE borrows from Pagnol’s own experiences as a student in a provincial town, a schoolteacher, and the husband of an actress. Pierre Rouve’s adapted screenplay is beautifully literate, giving Sellers the opportunity to imbue his high-minded character with the intelligence that will serve him well in the latter stages of the film. In his only outing as a director, Sellers employs an exaggerated mise-en-scène to reveal character that is sheer eye candy, but largely directs his cast—including himself—to underplay their roles. Only McKern is flat-out hilarious, but Sellers indulges briefly in some of the bumbling pratfalls that will reach their height in the Pink Panther movies and Hunt’s performance of the song “I Like Money” is a sparkling highlight. This comic gem digitally restored from the only surviving 35mm print is, in its way, a coming-of-age story that has a tinge of sadness about it. Highly recommended. (1961, 97 min) MF

Hong Sang-soo’s WOMAN ON THE BEACH (South Korea)

Available to rent through Facets Cinémathèque here

Just as Jean-Luc Godard described SAUVE QUI PEUT (LA VIE) as his “second first film,” so does WOMAN ON THE BEACH feel like a declaration of purpose for the second phase of Hong Sang-soo’s career. The film is markedly gentler than any of the South Korean writer-director’s previous six features, notably lacking in discomforting, graphic sex scenes or depictions of emotional abuse. That’s not to say that Hong abandoned his ongoing critique of toxic masculinity or that his characters became nicer; rather, he just started communicating his skeptical worldview under deceptive rays of sunshine. Indeed, WOMAN ON THE BEACH plays like a just-slightly acidic variation on one of Eric Rohmer’s vacation-set comedies, with lovely passages of flirtation and relaxed time-killing that reflect how people behave differently when they depart from their normal routines. The film, like many of Hong’s, is divided into two halves. In the first, a filmmaker named Kim Joong-rae takes a trip to a resort town on South Korea’s west coast with Chang-wook, his former production designer, and Moon-sook, a young female composer that the production designer has started seeing. Chang-wook thinks he’s having an extramarital affair with Moon-sook, but she’s quick to point out (in a great moment of Hongian micro-aggression) that there’s no chemistry between them; this inspires Joong-rae to make his move on the unattached woman. The director succeeds in seducing the composer but keeps his conquest secret so as not to anger the jealous Chang-wook. In the second half of the film, the three characters return to Seoul, then Joong-rae goes back to the resort town a couple days later to continue procrastinating on his latest script. He invites Moon-sook to join him, but when she doesn’t respond to his voicemail, he goes about seducing another female tourist instead. As in all his bifurcated narratives, Hong develops fascinating rhymes between the two parts of the film, showing how people without self-awareness fall into cycles of bad behavior. But for perhaps the first time in his work, the director seems to regard his antihero as a laughable fool as opposed to a malign soul. Joong-rae’s blinkered vision yields some of the funniest scenes Hong had created up till this point—the character’s poorly drawn diagram of his feelings for Moon-sook is particularly riotous. (2006, 129 min) BS

LOCAL ONLINE SCREENINGS – Held Over/Still Screening/Return Engagements (Selected)

Claude Sautet's CLASSE TOUS RISQUES (France)

Available to rent through Facets Cinémathèque here

[Note: Spoilers!] Although Claude Sautet directed his first feature film BONJOUR SOURIRE! in 1956, he aptly chose CLASSE TOUS RISQUES to mark the beginning of his career. Adapted by Sautet, Jose Giovanni, and Pascal Jardin from Giovanni's novel, CLASSE TOUS RISQUES stars Lino Ventura as Abel Davos, a wanted criminal who hopes to return to Paris in order to escape the Italian police closing in on him. Travelling with his wife Therese (Simone France), two young children, and friend Raymond Naldi (Stan Krol), Davos first reaches the small city of Menton on a gloomy French Riviera. Ambushed by border patrol, Davos and Naldi engage in a gunfight that ends with the death of Naldi as well as Therese. Eventually, a kind stranger, Eric Stark (Jean-Paul Belmondo), drives Davos and his children to Paris, but once there, Davos must contend with his former partners who turn on him in addition to the police. According to Giovanni's close friend and collaborator Bertrand Tavernier, all of his novels and screenplays center on the connected themes of survival and the dread of compromise or betrayal. In CLASSE TOUS RISQUES, the existential protagonist only lives while on the run through cities beautifully realized through Sautet's preferred Italian Neorealist lens. Davos can no longer face the victims of his crimes; he does not want to remain a criminal, but he is unsure of where to go and what to do. So, he stays on the run to nowhere until he realizes his own literal nothingness. In a recent essay on CLASSE TOUS RISQUES, Tavernier praised Sautet's new crime film, "Like Jacques Tourneur, Sautet renew[ed] the genre, profoundly, from the inside, instantly turning dozens of contemporary films into dusty relics... [He] succeeded in infusing his action scenes with absolute authenticity, breathing such an incredible sense of real life into them that it is said they won him the admiration of Robert Bresson." (1960, 110 min) CW

Hong Sang-soo’s HILL OF FREEDOM (South Korea)

Available to rent through Facets Cinémathèque here

Hong Sang-soo has loved playing with narrative structure since the beginning of his career. He’s organized many of his films around formal conceits, such as splitting the story in two and focusing on different characters in each part (as in THE POWER OF KANGWON PROVINCE or A TALE OF CINEMA), presenting variations on the same sets of scenes (as in THE DAY HE ARRIVES or RIGHT NOW, WRONG THEN), or shifting unexpectedly between reality and the characters’ dreams (as in NIGHT AND DAY, IN ANOTHER COUNTRY, or NOBODY’S DAUGHTER HAEWON). Then there are Hong’s puzzle films, in which the writer-director deliberately withholds crucial information from the viewers or else centers the film on some unresolved mystery. The short but dense feature HILL OF FREEDOM belongs to this latter category. At the start of the film, a Korean woman returns to Seoul after an extended stay at a sanatorium in the mountains; she finds waiting for her at home a stack of letters written to her by the Japanese man with whom she once taught at a language institute. Before she can read the letters, though, the woman drops them and, since the letters aren’t numbered or dated, she’s unable to put them back in the correct order. HILL OF FREEDOM proceeds to realize the contents of the letters in the sequence the woman reads them, which is to say that the chronology of events remains enigmatic till the end. Certain incontrovertible facts emerge from the flashbacks: Mori, the Japanese visitor, is an unemployed man who longs to reconnect with the woman he’s writing to, having identified her as his feminine ideal; he’s awkward when it comes to communicating with the older Korean woman who runs the inn where he stays in Seoul (their interactions giving way to some classic moments Hongian social awkwardness); the innkeeper’s nephew, whom Mori befriends, is saddled with many debts; and the woman who runs a coffee shop near the inn takes a shine to Mori. The gifted actress Moon So-ri (OASIS, THE HANDMAIDEN) plays the coffee shop owner, in her third collaboration with Hong; her winning yet vulnerable characterization is reason alone to watch the film, yet all of the characters generate fascination. HILL OF FREEDOM is one of the few Hong films of the 2010s that doesn’t focus on film professionals or other creative types, and one of the film’s pleasures lies in seeing Hong explore new patterns of behavior. Some of the more commanding insights concern the interactions between Japanese and Korean individuals and the romantic encounters between people who know their time together is fleeting. These insights take a few viewings to take root in one’s thoughts, since the formal invention is so attention-grabbing the first time around. Given how short the film is, though, you can easily find time to watch it twice in a day. (2014, 67 min) BS

Bill Duke’s THE KILLING FLOOR (American Revival)

Available for rent through the Gene Siskel Film Center here

A rare American labor union drama centered on Black experience, THE KILLING FLOOR is a minor miracle of narrative history, succeeding as drama, as pedagogy, and as a model of independent, inclusive, collaborative, local, unionized filmmaking. Shot in Chicago in 1983 for PBS’s American Playhouse series—an indispensable platform for some of the best independent filmmaking of the era, and a haven for voices and stories far outside the Reagan-era mainstream—THE KILLING FLOOR tells the story of Frank Custer (Damien Leake), a Black sharecropper who travels north to work in a stockyard during World War I. Eager to improve his wages and to reunite his family in the “Promised Land” of Chicago’s flourishing south side, Custer defies the ridicule of fellow Black workers to join a scrappy, mostly-white labor union. When the war ends and white veterans begin returning to the workforce (and to zealously segregated neighborhoods), racial tensions inside the union and out boil over, resulting in the violent 1919 riot that left dozens dead and displaced thousands of mostly Black residents. Producer and co-writer Elsa Rassbach, with a perspicacity uncommon today (let alone in the 1980s), found her way into this frayed historical knot through a footnote in William Tuttle’s book on the riot—a reference to a court record of a labor dispute between Custer and “Heavy” Williams (portrayed in the film by Moses Gunn), a Black stockyard worker whose vocal distrust of white unionists helped the packing company disrupt union organizing across racial lines. Thanks largely to director Bill Duke’s handling, what could have been a binary conflict between Williams’ pessimism and Custer’s idealism becomes remarkably nuanced—after all, Custer has justifiable misgivings of his own, and the film’s central dramatic question is whether his belief in the union can withstand the corrosive racism of its membership. Duke weighs Custer’s ambivalence through performance and point of view, as demonstrated in Frank’s first visit to the Union hall. Taking in the hectic air of jubilation and multilingual speechifying, Leake’s darting eyes register the white faces and powderkeg atmosphere with both wariness and enticement, his voiceover comparing the gathering to a Southern prayer meeting. In this sequence and throughout, THE KILLING FLOOR draws on familiar tropes and narrative conventions, but lends them a charge by introducing an alienated Black gaze to typically white spaces, pointedly validating the cultural knowledge that Black southerners bring as spectators to both the union hall and the historical drama. Celebrated dramatist Leslie Lee’s screenplay further makes virtues of archetypes and blunt expository dialogue; such immediacy is critical to the film’s educational economy, which captures the riot’s myriad underlying causes—the Great Migration, the First World War, the growth of organized labor, the European diasporas, and the centuries of exploitation and disenfranchisement of African Americans—in broad yet affecting strokes. But the film is also rich in detail and atmosphere, a quality starkly revealed in this new digital restoration by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, making its international debut just in time for the 100th anniversary of the 1919 Chicago riots. The renewed digital clarity also exposes some rough edges, of course—that’s to be expected from an ambitious historical drama funded largely by labor unions and populated with volunteer extras (including many from the Harold Washington mayoral campaign). Seen today, that roughness reminds us that THE KILLING FLOOR wasn’t so much a product of its time as a renegade in it—and a treasure in ours. (1985, 118 min) MM

LOCAL ONLINE SCREENINGS – Also Screening/Streaming

Full Spectrum Features

FSF presents Chicago Cinema Exchange: Mexico City, a series of three free programs of contemporary Mexican films and accompanying Q&A sessions. The series begins on Tuesday and continues through July 12. Schedule and more information here.

Gallery 400 (UIC)

Zakkiyyah Najeebah's 2017 video short DE(LIBERATE) (11 min) is on view through June 28 here.

Asian Pop-Up Cinema

Toru Hosokawa’s 2019 Japanese film THE HIKITA’S ARE EXPECTING! (102 min) is available for streaming on Friday; Yuki Tanada’s 2016 Japanese film MY DAD AND MR. ITO (119 min) is available for streaming on Saturday; and Shinobu Yaguchi’s 2017 Japanese film SURVIVAL FAMILY (117 min) is available for streaming on Sunday. All are free, but have a limited number of slots. More info here.

Chicago Filmmakers

Visit here to find out about virtual screenings offered through Chicago Filmmakers.

Facets Cinémathèque

Jeremy Hersh’s 2020 film THE SURROGATE (93 min), Peter Medak’s 2018 Cyprian documentary THE GHOST OF PETER SELLERS (93 min), Channing Godfrey Peoples’ 2020 film MISS JUNETEENTH (103 min), and Mounia Meddour’s 2019 Algerian/French film PAPICHA (108 min) also stream this week.

Gene Siskel Film Center

Jeffrey McHale’s 2019 documentary YOU DON'T NOMI (92 min), Stephane Démoustier’s 2019 French/Belgian film THE GIRL WITH A BRACELET (95 min), and Jeremy Hersh’s 2020 film THE SURROGATE (93 min) are all available for streaming beginning this week. Check here for hold-over titles.

Music Box Theatre

Rauzar Alexander’s 2018 documentary CREATING A CHARACTER: THE MONI YAKIM LEGACY (118 min), Dani Menkin and Yonatan Nir’s 2019 documentary PICTURE OF HIS LIFE (82 min), and Philippe Faucon’s 2019 French three-part episodic film PROUD (156 min) are all available for streaming beginning this week. Check here for hold-over titles.

Chicago International Film Festival

Check here for titles currently available for rental from CIFF’s Virtual Cinema.

Chicago Latino Film Festival

CLFF is offering a selection of features and shorts for rental. Information here.

Chicago Film Archives

Mike Gray and Howard Alk's 1969 documentary AMERICAN REVOLUTION 2 (77 min) is available on the CFA’s Vimeo page here.

The Film Group’s 1966 short documentary CICERO MARCH (8 min) is available for free at the CFA’s YouTube page here.

The Nightingale

The Videofreex’s 1969 video interview FRED HAMPTON: BLACK PANTHERS IN CHICAGO (23 min) is streaming for free here. Additionally, the Nightingale has a lengthy list of places that you can make donations to and they are offering passes to the Nightingale for individuals who make donations to ten of the organizations (any amount).

ADDITIONAL ONLINE RECOMMENDATIONS

Masaki Kobayashi’s KWAIDAN (Japan)

Available to stream on the Criterion Channel (subscription required)

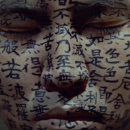

KWAIDAN is a beautiful three-hour anthology of ghostly folk-tales in which Masaki Kobayashi patiently deploys all the bells and whistles of film style to cast his spell. Though Kobayashi defers to no one at evoking a sense of dread, one watches the film today primarily to savor its cinematic mastery and unexpected emotional resonance. It adapts four tales from a 1904 Lafcadio Hearn collection of supernatural legends well-known to Japanese audiences. The first fable, “The Black Hair,” made me think of Mizoguchi’s UGETSU (1953); it tells of a peasant swordsman (Rentarô Mikuni) who abandons his loving wife (Michiyo Aratama) for what he imagines to be greener pastures, only to return after many years to find her as seemingly doting as ever. The denouement here is rather more unforgiving than in the Mizoguchi. “The Woman of the Snow” is gorgeous and unexpectedly romantic. It features Kurosawa regular Tatsuya Nakadai as a lumberjack whose life is spared by a killer Yuki-onna, or “snow woman” (Keiko Kishi)—on the condition that he never speak of the incident. This segment evokes a wintry world of frosty white and blazing painted skies full of giant eyes. What’s more, as critic Mike D’Angelo has pointed out, “if you’re curious about the origins of the J-horror creepy woman (as seen in The Ring, The Grudge, etc.), this is one place to look.” It also contains an erotic shot you sure wouldn’t see in a Hollywood film of the era (the segment was cut for American audiences, putatively for reasons of length). By far the longest tale is the third, “Hoichi The Earless.” The slow build is the source of KWAIDAN’s overall power, but this is the one sequence where the narrative can be felt to slacken a bit. It follows a blind monk who is an expert at singing the epic poem of the Battle of Dan-no-ura (1185). One night, he is summoned to a temple of dead souls, presided over by the ghosts of the defeated samurai clan of whom he sings. It seems they enjoy hearing the song of themselves. Trouble is, once you obey a spirit, you’re possessed—so the monk, to save himself, must be painted from head to toe in the characters of the Heart Sutra, rendering him invisible. Here is the most famous image from KWAIDAN—a body covered in script. The sequence reaches its climax as the monk’s singing gains in intensity—it can be enjoyed for its buzzing biwa playing and sutra singing alone (and Toru Takemitsu’s soundscape is innovative throughout). The unfinished “In a Cup of Tea” brings the idea of “the anxiety of influence” to life, with the tale of a writer who is haunted by the reflection of someone else’s face staring back at him from the titular cup. Shot in glorious “TohoScope” by Yoshio Miyajima, KWAIDAN utilizes the occasional striking location, but is primarily remembered for its massive sets—marvels of detailed, handmade art direction (by Shigemasa Toda) and set design (by Dai Arakawa) that brilliantly borrow techniques from theater and Expressionist painting. It’s a veritable film school course in terms of its orchestration of lighting, costume, color, space and time, mobile framing, and cutting. This film thrilled me—one of the things I ask of a movie is that it usher me into a dream-world via a storehouse of powerful imagery. KWAIDAN is the kind of immersive formal and sensory experience I have in mind when I think of the term “cinema.” (1964, 180 min) SP

Cheryl Dunye’s THE OWLS (US)

Available to stream on the Criterion Channel (subscription required)

In her seminal entry into New Queer Cinema, THE WATERMELON WOMAN (1996), Cheryl Dunye imagined a Black queer woman—like herself—as an old Hollywood star, the search for whose identity comprises the plot of the film. Fourteen years and three features later, another sort of imagined history, again bleeding into the present (this time literally), is at the heart of THE OWLS, made by Dunye as part of the Parliament Film Collective, a group of queer artists who communally developed the film from a script by Sarah Schulman based on a story idea by Dunye. Similar to the bygone Watermelon Woman, the Screech is put forth as a band that was relevant sometime prior; its frontwoman Iris (Guinevere Turner, from GO FISH and THE WATERMELON WOMAN, as well as co-writer with Mary Harron on several of her films) is a narcissistic alcoholic who’s still in a relationship with the band’s producer, MJ (V.S. Brodie, also from GO FISH), while supercilious Lily (Lisa Gornick) has overcome her own addictions and settled down with Carol (Dunye), the two debating whether to have a child. The film opens with a party at which all these women are present; intercut admist it are talking-head-style interviews with the characters, implying but not fully elucidating that something has happened to a young woman named Cricket (Deak Ergenikos), who also appears despite, as we later discover, having been killed at the party and her body disposed of by the older women. What follows is the relative deterioration of these couples and their collective falsehood, which is compromised by Skye (Skyler Cooper), an enigmatic interloper who shows up on Lily and Carol’s doorstep and insinuates themselves into the group’s already fucked-up dynamic. As fits her signature style—the Dunyementary, a label that embodies the self-reflexiveness that distinguishes much of her work—Dunye weaves interviews with the film’s cast and crew into the narrative, which are presented in the same documentary-like mode, the two sometimes difficult to distinguish. The underlying theme of the film is the protagonists’ experiences of being older, and thus supposedly wiser, lesbians, hence the connection to owls. Something of an autoethnography, as Dunye and the rest of the cast—which, along with the crew, comprises a who’s who of lesbian cinema—are in their 40s, the film considers what it means to have been at the forefront of a movement and then later forsaken by those for whom you’ve helped pave the way (though the Collective’s mission and the inclusion of their testimony at the end is altogether more hopeful than the narrative suggests). Where THE WATERMELON WOMAN explored a history removed from its protagonist, this considers a more personal history, one that exists in the present and is crystallized through aging. And as with all of Dunye’s films, the engaging ambience and the complexity of its construction account for the visceral pleasure of watching it. (2010, 66 min) KS

Theodore Collatos and Carolina Monnerat’s QUEEN OF LAPA (Brazil/Documentary)

Available for rent from various “virtual cinemas” via Factory 25 here

Brooklyn-based filmmaker Theodore Collatos is best known for directing the impressive micro-budget narrative features DIPSO (2012) and TORMENTING THE HEN (2017), the latter of which stars his wife, the gifted Brazilian actress Carolina Monnerat. QUEEN OF LAPA is a cinema verité documentary in which Monnerat teams up with Collatos behind the camera to ostensibly chronicle the legendary Brazilian transgender prostitute-turned-activist Luana Muniz. The film’s title is somewhat misleading, however, as this doc is as much about the group of younger trans sex workers that Muniz has taken under her wing, and who reside in a hostel she runs in Rio de Janeiro’s Lapa neighborhood, as it is about the colorful matriarch Muniz herself. Unlike most movies (fiction and non-fiction alike) that take prostitution as their subject, QUEEN OF LAPA seems to studiously avoid depicting interactions between sex workers and johns, the latter of whom are virtually nowhere to be seen, and focuses instead almost exclusively on the sisterhood of these vibrant young women who live and work together under the same roof. One memorable scene shows a conversation between two friendly rivals about whether or not it’s ethical to enjoy sex when one is being paid for it. Another features a prostitute, standing alone by a window, taking a flat iron to her wig while simultaneously recalling stories about the earliest clients she had when she was still a child. What these remarkable scenes, and others like them, have in common is a tone of quiet authenticity that can only be achieved when an unusually high degree of mutual trust is established between filmmaker and subject. It’s a compassionate and non-sensationalistic look at the inside of a subculture that most viewers will be unfamiliar with. So much of QUEEN OF LAPA takes place inside the House of Muniz, in fact, that it ends up becoming a fascinating portrait of an interior world whose denizens have established their own rules; or as Muniz herself poetically puts it, it's “one of the last communities where humans can dream.” This self-enclosed, self-created world is thrown into stark relief whenever Collatos and Monnerat’s camera does venture out into the streets or into a nearby cabaret nightclub where the larger-than-life Muniz performs an awesome slow-motion dance number to a karaoke version of an Elton John song. All of which is to say, this is perfect Pride-month viewing. (2019, 83 min) MGS

Matt Wolf’s RECORDER: THE MARION STOKES PROJECT (Documentary)

Currently available for free through PBS here

In 1975, Marion Stokes started recording and never stopped. From then until her death in 2012, Stokes had as many as eight separate Betamax and VCR machines recording network and local news around the clock, ultimately amassing over 70,000 tapes and an invaluable archive of that most American of concepts: the 24-hour news cycle. After viewing Matt Wolf’s RECORDER: THE MARION STOKES PROJECT, Stokes might well be described as a visionary; the film, a straightforward but compelling account, details not just Stokes’ project, which serves as the film's through line, but also her life overall. I was previously unfamiliar with Stokes, so I’m grateful to the film for elucidating the biographical details surrounding the project: a Black woman born into less-than-ideal circumstances, Stokes was empowered to pursue her unconventional interests after marrying John Stokes, Jr., a kindred spirit with whom she co-hosted a Sunday morning TV talk show in Philadelphia that was centered around current affairs. The film explores her relationships with the people in her life, ranging from her son from a previous marriage to Stokes and his children to her household staff, which included a secretary, a driver, and a nurse. These people not only explain Stokes’ preoccupation with taping things—detailing her commitment to recording the news at all hours of the day, even rushing home to change out the tapes—but the impetus behind her decision to do so. Stokes was eccentric, sure, but also intelligent and decidedly ahead of her time, specifically with regards to how she recognized the 24-hour news cycle as a driving force behind the fast-changing socio-political landscape. Naturally, Wolf uses footage from Stokes’ collection, now in the possession of the Internet Archive, to punctuate the narrative of her life story. The footage ranges from ironically humorous to unironically disconcerting to genuinely terrifying, the latter evidenced in the expanded footage from 9/11 and various incidents of widespread racial violence. It’s clear from these sections how the broadcasts influenced our understanding of the events in question, lending weight to Stokes’ goal in creating her archive: news broadcasts can show us what memory has either transformed or altogether erased, as these things were unfolding in the moment, an embalmed sense of urgency made palpable all these years later. Whether that’s good or bad is up to the viewer. At one point in the film, someone remarks that we’d taken for granted that news stations would keep recordings of all their broadcasts. As it turns out, that’s not the case, and collections like Stokes’ are often all that remains, imparting to us the importance of physical media as well as its content. Like Stokes herself, there’s more to the film than meets the eye—one will come away not only having learned more about this extraordinary, if sometimes neurotic, woman, but also about our society’s relationship to that which she was trying to preserve. (2019, 87 min) KS

SUPPORT LOCAL THEATERS AND SERIES

As we wait for conditions to improve to allow theaters to reopen, consider various ways that you can help support independent film exhibitors in Chicago weather this difficult time. Memberships, gift cards, and/or merchandise are available from the Gene Siskel Film Center, the Music Box Theatre, and Facets. Donations can be made to non-profit venues and organizations like Chicago Filmmakers, the Chicago Film Society, South Side Projections, and many of the film festivals. Online streaming partnerships with distributors are making films available through the Gene Siskel Film Center, the Music Box Theatre, and Facets; and Facets also has a subscription-based streaming service, FacetsEdge, that includes many exclusive titles.

COVID-19 UPDATES

All independent, alternative, arthouse, grassroots, DIY, and university-based venues and several festivals have suspended operations, closed, or cancelled/postponed events until further notice. Below is the most recent information we have, which we will update as new information becomes available.

Note that venues/series marked with an asterisk (*) are currently presenting or plan to do regular or occasional “virtual” online screenings.

Asian Pop-Up Cinema – See above for online offering; otherwise, spring series postponed till the fall*

Beverly Arts Center – Events cancelled/postponed until further notice

Block Cinema (Northwestern University) – Events cancelled/postponed until furtuer notice*

Chicago Film Archives – The CFA’s annual “Media Mixer” event, previously scheduled for May, has been rescheduled for September 16

Chicago Film Society – Events cancelled/postponed until further notice

Chicago Filmmakers – Events cancelled/postponed until further notice*

Comfort Film (at Comfort Station) – Programming cancelled with no set start date

Conversations at the Edge (at the Gene Siskel Film Center) – Events cancelled/postponed until further notice

Doc Films (University of Chicago) – Screenings cancelled until further notice

Facets Cinémathèque – Closed until further notice (see above for “virtual” online screenings)

Film Studies Center (University of Chicago) – Events cancelled/postponed until further notice

filmfront – Events cancelled/postponed until further notice

Gallery 400 *

Gene Siskel Film Center – Closed until further notice (see above for “virtual” online screenings)

Music Box Theatre – Closed until further notice (see above for “virtual” online screenings)

The Nightingale – Events cancelled/postponed until further notice

The Park Ridge Classic Film Series (at the Park Ridge Public Library) – Events cancelled/postponed until further notice

Festivals:

The Cinepocalypse film festival (June) – Postponed with plans to reschedule at a future time

The Chicago Latino Film Festival (April 16-30) – Postponed with plans to reschedule at a future time

The Windy City Horrorama festival (April 24-26) – Cancelled; will possibly be rescheduled or reconfigured at a future date

The Chicago Critics Film Festival (May 1-7) – Postponed until further notice

The Chicago Underground Film Festival (June 10-14) – Postponed (tentatively in September)

CINE-LIST: June 19 - June 25, 2020

MANAGING EDITOR // Patrick Friel

ASSOCIATE EDITORS // Ben Sachs, Kathleen Sachs, Kyle A. Westphal

CONTRIBUTORS // Marilyn Ferdinand, JB Mabe, Michael Metzger, Scott Pfeiffer, Michael Glover Smith, Candace Wirt