NOTE: Cine-File contributors and associate editors Kathleen Sachs and Ben Sachs are hosts for Movie Trivia at the Gene Siskel Film Center tonight (Friday) from 6:30-8pm. Open to ticket holders for any Friday night screening at the Siskel.

CRUCIAL VIEWING

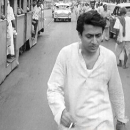

Mrinal Sen’s INTERVIEW (Indian Revival)

Block Cinema (Northwestern University) — Thursday, 7pm (Free Admission)

With INTERVIEW, the first feature in his celebrated Calcutta trilogy, Marxist filmmaker Mrinal Sen delivers a political movie that’s never stodgy nor overwhelmed by rhetoric. In fact, the movie is vibrant and formally inventive, recalling Jean-Luc Godard not in his own political period (when he made some of his worst films) but at his 1966-67 peak. INTERVIEW contains an extraordinary sequence in which the star, Ranjit Mallick (who’s also playing a character named Ranjit Mallick), breaks the fourth wall to discuss his background, how he came to be in a film, and some insights into the Bengali economic system. During the sequence, Sen briefly turns the camera on his own crew, alerting viewers to the fact that this documentary-like passage is also a cinematic construct. The act of baring the device is a familiar trope of modernist fiction and drama, but Sen gives it a political edge by suggesting he and his crew belong to the same economic system as the one his star rails against. No matter what, Sen implies, we’re always working under capitalism. The film’s story is like a fable; Mallick is so single-minded in his quest to climb the social ladder that he comes to seem like a timeless folk character. At the same time, Sen renders INTERVIEW immediate through his use of eclectic cinematic devices: in addition to breaking the fourth wall, Sen employs expressionistic sequences and scenes of neorealist-style drama. The movie is exciting and unpredictable—it allows itself to change, somewhat ironically given that its subject is the lack of political consciousness among the Bengali middle-class. Mallick’s character is obsessed with a potential new job that pays more than twice as much as his current one and which would allow him to advance in society. The job is pretty much guaranteed (he has an in with the hiring manager), so long as he shows up to an obligatory interview wearing a Western-style suit. Yet Mallick doesn’t procure the right clothing on time—in his blinkered vision, he fails to notice that the laundry workers he trusted with his only Western-style suit would go on strike before they could clean it. A righteous but never self-righteous film, INTERVIEW modulates its anger with wry wit and playful style. (1971, 80 min, DCP Digital) BS

---

Kunal Sen, son of the late director, will introduce the film and take part in a discussion afterward.

Bertrand Bonello’s ZOMBI CHILD (New French)

Gene Siskel Film Center — Check Venue website for showtimes

The most recent addition to Bertrand Bonello’s roster of dark, spellbinding films expertly shifts focus away from haute couture (SAINT LAURENT, 2014) and political terrorism (NOCTURAMA, 2016) to Voodoo, colonialism, and the magical ties that bind. Inspired by the legend of Clairvius Narcisse, ZOMBI CHILD takes place across two timelines. In 1960s Haiti: Clairvius gets struck by illness, zombified, and is forced to live the rest of his undead days as a sugarcane farmer. In modern day France: Mélissa is the fictional descendant of Clairvius and the only Black girl at her all-girls boarding school. She gets adopted into a popular friend group when she reveals her aunt is a Voodoo mambo. What follows is the unraveling of a mystical family history, and an apt commentary on the appropriation of Voodoo magic in a colonialist society. Mélissa quickly realizes her newfound friendships are more transactional than she’d like when her best friend Fanny becomes obsessed with the idea of using magic to win a boy’s heart. And as the two timelines converge in unlikely ways, strange, unexplainable things start to happen to Mélissa. ZOMBI CHILD’s politics are refreshing—both in its treatment of a spirituality that’s often depicted in media without cultural context, and its criticisms of French academic institutions that reek of impenetrable wealth and privilege—while its style is charmingly peculiar. It takes its time to get where it’s going, but the second it gets there, ZOMBI CHILD is a remarkable musing on the intrinsic power of legends. It’s a different kind of zombie film that horror fans will surely keep coming back to. (2019, 103 min, DCP Digital) CC

Fridrikh Ermler’s FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE (Silent Soviet Revival)

Film Studies Center (at the Logan Center for the Arts, 915 E. 60th St., University of Chicago) – Friday, 7pm (Free Admission)

Fridrikh Ermler’s 1929 Soviet film FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE is a curious hybrid of styles and tones. It was made at the tail end of the silent era in the Soviet Union, after several years of modernist editing on display in films by Ermler's contemporaries (Kuleshov, Eisenstein, and Vertov most prominently), but begins almost like something made a decade before. It’s the story of Filimonov, a soldier who has lost his memory and any sense of his identity. He’s working in a rural town near the train station, and one wonders whether the film might be derived from Gogol or another pre-Soviet realist author, given the starkness of the setting and the earthiness of some of the action. But after Filimonov happens to see his wife in a train window, he suddenly recalls everything and the conventional film style up to that point turns 180 degrees with a fantastically percussive montage sequence, reflecting the shock of his returned memory. Filimonov decides to travel to his hometown, St. Petersburg, but is dismayed and confused by its transformation into Leningrad, the modern urbanity and new socialist reality both providing shocks to his system. Here, the film plays in a more parodic fashion, resembling films by Kuleshov or Medvedkin, as Filimonov becomes acclimated, then fully embraces the radical egalitarianism of the new system (again, his flash of realization is presented via a stunning montage sequence). Ermler was noted for his later films’ by-the-book propaganda, and the last third of FRAGMENT is certainly not subtle in its messaging. The excessiveness of it, though, almost plays like comedy, but the film retains an empathy towards Filimonov and never becomes satirical in tone. Throughout, Ermler displays great control over the filmmaking, navigating the sometimes swift changes in style and tone effortlessly and incorporating some mesmerizing imagery (some of which is quite surreal—including a gas-masked Jesus hanging on a cross, one of several moments returned to the film in this restored version). Ermler may not be one of the most noted filmmakers of 1920s and 30s Soviet filmmaking, and I can’t speak to the rest of his work; but this, while not comparable to the best of Pudovkin, Eisenstein, or Dovzhenko, and a bit drawn-out and slow going at times, is still an amazing achievement. (1929, 109 min, 35mm restored print) PF

---

With Peter Bagrov (George Eastman Museum) and Robert Bird (Univ. of Chicago) in conversation. Live accompaniment by Donald Sosin.

ALSO RECOMMENDED

William Dieterle’s (and David O. Selznick’s) PORTRAIT OF JENNIE (American Revival)

Chicago Film Society (at Music Box Theatre) — Monday, 7pm

Also known as the film that brought down David O. Selznick, PORTRAIT OF JENNIE was plagued by innumerable re-writes and re-shoots, the latter being quite costly as the producer insisted on filming on location whenever possible. JENNIE ended up costing more than Selznick’s GONE WITH THE WIND, despite running less than half as long; the movie failed to recoup its large budget on first release, effectively signaling its auteur’s demise. None of this is to say that JENNIE is a bad film—it’s certainly not uninteresting, as it exudes a strangeness comparable to that of PETER IBBETSON, another supernatural romance that showcases Hollywood filmmaking at its most madly perverse. Joseph Cotten stars as a struggling painter in Depression-era Manhattan. Searching for inspiration, he finds his muse in the form of a 12-year-old girl played by the clearly grown-up Jennifer Jones. The painter bumps into the girl several more times, and their cheerful banter becomes increasingly (and creepily) flirtatious. There are some odd things about Jennie: she claims her parents perform in a trapeze act at a local circus, though the theater where she says they perform shuttered decades ago; much of the culture she references is a generation off; and each time Cotten sees her (which is about every few weeks), she seems to have aged a few years. If you guessed that Jennie is a ghost, you’re not only correct, but several steps ahead of the narrative, which holds off its big reveal for far longer than it should. But the film has more going on than plot twists; it’s a sincere meditation on the creative process, the role of fate in romance, and the seductive charms of New York City. The cinematography, by Joseph August (who died during the lengthy production), goes a long way in elucidating the first and third of these themes. Sometimes shooting with a canvas over the lens, August makes the film seem like a painting come to life—or is it life as seen through the filter of fine art? JENNIE may not be the timeless masterpiece Selznick envisioned, but it still contains plenty to swoon over. (1948, 86 min, 35mm) BS

---

Preceded by Will Vinton and Bob Gardiner’s 1974 animated short CLOSED MONDAYS (8 min, 35mm).

Juraj Herz's BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (Czech Revival)

Gene Siskel Film Center — Saturday, 3pm and Monday, 8:15pm

Czech/Slovak director Juraj Herz’s adaptation of this well-known story is decidedly darker (visually and thematically) than Jean Cocteau’s classical, mythic vision (1946) and Disney’s pop romanticism (1991). It hints more strongly at the Beast’s psychological and existential torment. A pervasive sense of dread overhangs the film. It moves toward horror, then pulls back. It subtly threatens the possibility of sexual violence, then doesn’t go there. Its palette is dominated by muddy browns, but with occasional bursts of color. Its use of lighting conceals more than it reveals. The camera work is voyeuristic, almost stalking at times, yet still graceful. The Beast is a harrowing bird-man (inspired perhaps by Max Ernst’s photocollages), with menacing claws, feathers that are scale-like, and a beak ready to rend flesh at a moment’s notice, but with soulful, human eyes. Throughout, Herz maintains a tension between unease and euphoria, one that invests the film with a sense of precariousness and danger. Fate here is more capricious; one senses that the story’s anticipated happy ending just might not happen. Or, if it does, one wonders whether it really is one. (1978, 84 min, DCP Digital) PF

We Tell: Environments of Race and Place (Documentary Revival)

Film Studies Center (at the Logan Center for the Arts, 915 E. 60th St., University of Chicago) — Thursday, 7pm (Free Admission)

The second program in the ongoing “We Tell: Fifty Years of Participatory Community Media" series, “Environments of Race and Place,” focuses on such hot-button issues as displacement, immigration, and racial discord. BLACK PANTHER [aka OFF THE PIG] (1967, 15 min) was produced by Third World Newsreel, an alternative media arts organization; it was urgent then and still feels so now. Reportedly found in FBI files by the National Archives and Records Administration, the newsreel features Black Panther party leadership (including interviews with Minister of Defense Huey P. Newton and Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver), footage of various demonstrations, and a recitation of the party’s Ten-Point platform by its co-founder Bobby Seale. The camera movements and editing are dizzying, mimicking the effect of what it feels like to have one’s world shaken to its core. Less urgent but still insightful is BLACK WOMEN, SEXUAL POLITICS, AND THE REVOLUTION (1992, 26 min) from Not Channel Zero, a video collective comprised of African American video artists based in New York City that produced programming for Manhattan Cable Access. The program features mostly Black women—some of whom hold important positions in non-profits and academia, others whom the producers seem to have found on the street—discussing topics in the realm of sexual politics and race-related activism. Their honesty is often dauntless and always awe-inspiring as they speak brazenly about topics that much of contemporary society still tiptoes around. The other works in this illuminating program include WHO I BECAME (Vietnamese Youth Development Center, 2003, 20 min), LEGEND OF THE WERESHEEP (Outta Your Backpack Media, 2007, 3 min), and AERIAL FOOTAGE FROM THE NIGHT OF NOVEMBER 20, 2016 AT STANDING ROCK (Digital Smoke Signals, 2016, 7 min). All Digital Projection. KS

---

Susan Gzesh (Executive Director, Pozen Family Center for Human Rights) and Alaka Wali (Curator of North American Anthropology at the Field Museum) will participate in a discussion after the screening.

Wim Wenders’ PARIS, TEXAS (German/French/American Revival)

Music Box Theatre – Tuesday, 7pm

One of the most revealing pieces of dialogue in PARIS, TEXAS occurs when, following a screening of an old family movie, the eight-year-old Hunter is getting ready for bed. Hunter had noticed the way his father Travis (Harry Dean Stanton), who’s just returned from an unexplained four-year estrangement, watched the footage of his wife Jane (Nastassja Kinski), who’s been absent for the same length of time. The boy explains to his adopted mother that he believes Travis still loves Jane. “But that’s not her,” he pointedly adds. “That’s only her in a movie.” A beat, as a cheeky smile forms across his face. “A long time ago. In a galaxy far, far away.” What begins as a remarkably lucid insight about the illusion of the cinematic image, and about the fantasies on which it hinges, can’t help but be capped off by a quote that then reinforces those very illusions. This is PARIS, TEXAS in a nutshell: a world of willful, even blithe mirages and imagos, in which all understanding of other people is mediated by the idealized myths of mass culture. Wenders is not above speaking the language of these myths, even as he meticulously dismantles them. Written by the all-American Sam Shepard and L. M. Kit Carson, the film radiates a love for the aesthetic and narrative iconography of the American West, from the wide-open tableaux of towering mesas and endless road to Travis’ rugged, archetypal masculine loner, whose quest to rescue a woman and tenuous attempts to reintegrate into society remix that of Ethan Edwards in THE SEARCHERS. Like so many other émigré artists ensorcelled and perturbed by the U.S., including compatriots like Douglas Sirk, Wenders doesn’t merely indulge in the grammar of Americana but defamiliarizes it to reveal, from an outsider’s critical distance, how truly melancholy, strange, and even menacing it can be. From Wenders’ vantage (and from the extraordinary camera of Robby Müller, who really hits the patriotic reds and blues copiously supplied by art director Kate Altman and costume designer Birgitta Bjerke), the West is no longer a grand frontier of imperialist expansion but a desiccated strip of roadside advertisements, diners, and motels. Not only is our would-be hero Travis a Man With No Name, he’s practically a Man With No Self, an icon emptied of past and presence and purpose, set to roam perpetually in the desert to which he’s withdrawn himself. He clings desperately to the idée-fixe of a measly plot of land he’s bought in Paris, which he and his parents wished was in France. Unfortunately, it’s really just in this godforsaken Southwestern dust bowl, and like Jane in that family movie, it’s nothing but an image. Travis’ illusions, and his dawning understanding of his need to atone for all the damage they’ve caused, finally lead to PARIS, TEXAS’ famous peep-show scenes, where mirrors and screens—those quintessential analogs of the cinema apparatus—give way, ironically, to piercing disillusions. In Wenders’ ambivalent but heartfelt ode to Americas dreamed and (uncertainly) lived, such revelations are a bittersweet matter of course. It’s what you do with them that counts. (1984, 145 min, DCP Digital) JL

Ida Lupino’s NOT WANTED (American Revival)

Doc Films (University of Chicago) — Wednesday, 7 and 9pm

Actress-director Ida Lupino was a great admirer of Roberto Rossellini, whose chosen mode, neo-realism, she counted as an influence. Before she produced, co-wrote, and directed NOT WANTED, she met Rossellini at a party, where he reportedly told her, “In Hollywood movies, the star is going crazy, or drinks too much, or he wants to kill his wife. When are you going to make pictures about ordinary people, in ordinary situations?” It would seem Lupino took this to heart, as is evidenced by many of her films, starting with NOT WANTED. She’d been seeking out a project to direct when she came across the film’s script, oversaw its development, then tweaked it herself. Her husband, Collier Young, presented it to Columbia Pictures head Harry Cohn, who refused to support or finance it. Lupino and Young soon joined forces with Anson Bond to form Emerald Productions (named after Lupino’s mother), and Lupino started on the project as a co-producer with Bond. After the hired director, Elmer Clifton, had a heart attack just days before shooting, Lupino took over—a change that resulted in the cast credits being prefaced with “Ida Lupino introduces”; she’s also credited as co-writer and co-producer, though she receives no credit for direction—and the result is a decidedly auspicious debut. Sally Forrest, whom Lupino more or less discovered and later cast in NEVER FEAR (1949) and HARD, FAST AND BEAUTIFUL (1951), stars as Sally Kelton, a young woman who falls in love with a fly-by-night pianist, Steve Ryan (played by Leo Penn, Sean Penn’s father), who impregnates her before he pulls up stakes, as he’d say. Sally follows him, only to meet Drew Baxter (Keefe Brasselle), a veteran with a leg injury and a big heart, on the bus. Having been brushed off by Steve, she goes to where Drew works and gets a job at his gas station. After Steve breaks up with her for good, she learns she’s pregnant. Sally goes to live at a home for unwed mothers where she gives birth to a son, then gives him up for adoption; the decision causes her to suffer a breakdown, and she tries to kidnap a baby on the street. The attempted kidnapping, resulting arrest, and the police’s decision to let her off due to her emotional struggles are the events that frame the film, Sally looking back on how she got to that point from the jail cell. After Sally leaves jail, she runs into Drew and then away from him, culminating in the film’s devastating final moments as the two, both broken but deserving of happiness, come together in an ambiguous embrace. The film’s subject matter was shockingly taboo at the time (Lupino worked with the Breen Office to make it more acceptable; ironically, she had nothing but nice things to say about the experience), but now, it’s the assured storytelling and astounding display of empathy that surprises. In fitting with Lupino’s neorealist aims, no character is completely good or bad—rather, every character is human. At first, Sally’s mother seems like a coldhearted shrew, the kind of mother that would drive even the most angelic of daughters to sin. Several scenes later, we see her interacting amiably with Sally, showing concern about her daughter tiring herself out. Even Steve is shown to be a tortured creative who aptly points out that he made no promises, that it’s his art, not a desire for domesticity, that motivates him. This may be a small film, but its characters are largely realized; even the nondescript settings (which were still shot on location, again like a neorealist film) are in service to its broader message. Henry Freulich’s cinematography enforces this, and William H. Ziegler’s smooth editing keeps it from feeling heavy-handed. As a result, the low-budget independent film was a success, earning Lupino respect among her peers for her filmmaking prowess. It’s fortuitous that a major woman director’s first film was about a prevalent women’s issue, but it’s undoubtedly Lupino’s handling of it that makes this a groundbreaking work. (1949, 91 min, DCP Digital) KS

Tsai Ming-liang’s THE RIVER (Taiwanese Revival)

Doc Films (University of Chicago) - Friday, 7pm and Sunday, 1pm

Splitting the difference between Buster Keaton and Michelangelo Antonioni, Tsai Ming-liang developed a new—and profoundly affecting—approach to both cinematic minimalism and urban alienation with his masterful third feature. The influence of Keaton can be felt in the film’s understated humor and in Lee Kang-sheng’s deadpan lead performance. His character expresses little outward emotion as the world caves in around him; his recalcitrance can be funny, poignant, or downright sad depending on the context of the scene. The influence of Antonioni can be felt in Tsai’s brilliant compositions (which render the landscapes of Taipei commanding and mysterious—the film, like all of Tsai’s work, looks awesome on a big screen) and in the purposeful ellipses of his screenplay. It isn’t clear for almost an hour of THE RIVER that the primary characters are husband, wife, and son, but it becomes clear as soon as all three appear together why the writer-director withheld their relationship for so long: these characters are thoroughly disconnected from each other and barely in touch with themselves. As is often the case in Tsai’s work, the protagonists long for love but find only empty sex. The father (played by Tien Miao, a wuxia film veteran whom Tsai cast against type) is a closeted homosexual who goes cruising in malls, while the mother is carrying on an affair with a man who sells bootleg porno videos. Lee’s character, Xiao-Kang, has a fling with an old friend near the start of the film, yet she mysteriously disappears soon after the two have sex. Before she vanishes, though, she lands Xiao-Kang a role in a movie she’s working on; he plays a corpse, and he’s required to float in a dirty river for an extended period of time. Somehow his neck becomes paralyzed as a result of doing this, and much of the rest of the film concerns his parents’ failed attempts to find a cure for his condition, which represents a manifestation of all three protagonists’ psychic discomfort. These failures are by turns funny and tragic, though you never know which direction the tone will take. Consistent, however, are Tsai’s awesome mise-en-scene and his deep understanding of what it’s like to be lonely in a modern city. (1997, 115 min, DCP Digital) BS

---

Showing with Tsai Ming-liang's 1996 documentary MY NEW FRIENDS (56 min, DCP Digital).

John Carpenter's THEY LIVE (American Revival)

Doc Films (University of Chicago) - Thursday, 7pm

A defiant take on Reagan's proto-fascism, THEY LIVE is an affectionate view of working-class Los Angeles that mirrors a sincere appreciation of disreputable pop culture. Casting pro wrestler "Rowdy" Roddy Piper as the leader of a working-class insurgency is one of the most audacious choices of John Carpenter's long career, and it may be the most crystallized expression of the director's politics. Carpenter's skepticism towards contemporary life is rooted less in ideology than in a loyalty to old-fashioned genre storytelling, whose handmade qualities have been endangered by the automated culture of the corporate age. THEY LIVE famously depicts the corporate network of banks, TV stations, and multinational businesses as a secret alien plot; and while this makes for an effective sci-fi premise, it's executed too often as camp to make for effective political filmmaking. (Far more resonant are Carpenter's images of shantytowns comprised of former factory workers—a subtle reference to the collective miseries of Depression-era cinema in an era obsessed with individual success.) But, of course, Carpenter never aspired to be George Romero: His virtues lie elsewhere, in eccentric character touches, dynamic action sequences, and a consistently inventive use of the 'Scope frame. It should be noted that Carpenter was one of the few Hollywood filmmakers who insisted on shooting in widescreen throughout the VHS era, when most mainstream movies were shot in narrower ratios to be ready, like lambs to the slaughter, for panning and scanning. (1988, 93 min, 35mm) BS

Brett Story’s THE HOTTEST AUGUST (New Documentary)

Facets Cinémathèque - Check Venue website for showtimes

Exactly how calm is the so-called "calm before the storm"? The definition of the phrase causes one to wonder: “A period of unusual tranquility or stability that seems likely to presage difficult times." If it’s unusual and likely to presage difficult times, just how calm can it be? In her new documentary THE HOTTEST AUGUST, director Brett Story (THE PRISON IN TWELVE LANDSCAPES) seems to be asking these questions about the apparent calm that's presaging the likely devastating effects that climate change will exact upon us, but rather than address the subject straightforwardly, something that’s been done before and will be done again (but always to little avail), Story instead takes a random month—August 2017—and uses various happenings within it, in New York City, to present a microcosm of a contemporary society plagued by anxiety over the future. Inspired by Chris Marker’s 1962 film LE JOLI MAI, which Marker filmed over one month in Paris, Story, like Marker, wields the footage literally and figuratively in equal turn. In some scenes, it’s either explicitly audible or otherwise implied that she’s addressing her subjects (of whom there is a diverse mix, from a charming working-class couple in the Bronx to an African-American man who often dons a homemade space suit around the city), asking them particular questions about their lives, their hopes, their dreams, their finances, their aspirations, their desires for the future, whether or not they think there will be a future at all. Other scenes are more observational and thus more ambiguous and open to interpretation. Among the most elliptical sequences are ones that take place at a sandcastle-building contest and a 1920s-themed party; Story admits to welcoming the randomness, though in the sense that such haphazard vignettes speak to both the deliberateness and chaos of daily life. As evinced by this and THE PRISON IN TWELVE LANDSCAPES, Story has a knack for making connections between seemingly benign scenarios and the larger point she’s trying to make, which, in this case, is that climate change is likewise a cause and an effect of contemporary society. Accompanying all this is voiceover narration of passages from Zadie Smith’s Elegy for a Country’s Seasons, Karl Marx’s foundational text Capital (naturally, capitalism is a factor in the film, even when it’s not), and Annie Dillard’s essay “Total Eclipse” (August 2017 was the year of the solar eclipse, as well as the Charlottesville incident in which activist Heather Heyer was killed by a white supremacist, incidents that serve to contextualize the randomness). These imbue the documentary with a gravitas that mirrors the significance Story imports upon her subjects, some more adventitious than others, but all crucial to it. The ataractic voiceover, gorgeous shots of day-to-day life in one of the most vibrant cities in the world, the subjects’ lack of a conspicuous emotional response to the mercilessness of the challenges they face—unusual tranquility, indeed, and certainly presaging the most difficult of storms. (2019, 95 min, DCP Digital) KS

Ladj Ly’s LES MISÉRABLES (New French)

Music Box Theatre – Check Venue website for showtimes

Testifying to the nearly unmatched power of sporting events to unite people across ethnic and class boundaries, Ladj Ly’s LES MISÉRABLES opens with rousing footage of French citizens flooding into the streets to celebrate their country’s 2018 World Cup victory. Ly focuses especially on exultant black faces, including those of characters officially introduced later, as he films this very real national eruption of joy. Accentuated by the Eiffel Tower and Arc de Triomphe looming on the horizon, the sequence encapsulates the foundational French tenet of fraternity, realized in one outsized moment of esprit de corps that Ly will soon show as utterly fleeting. There will be plenty more images of bustling congregations to come, but their animating communal pleasure will be replaced by melees of inequity-fueled desperation. Taking its inspiration from the 2005 suburban Paris riots, LES MISÉRABLES chronicles a 48-hour period of pullulating racial tensions in Clichy Montfermeil, where housing projects provide residence to many North African immigrants. Hewing closely to policier genre conventions, Ly uses an anti-crime unit as our initial point of entry to this world, introducing us to the coolheaded Gwada (Djebril Zonga) and the unapologetically racist sergeant Chris (Alexis Manenti), who’re joined by taciturn new recruit Stephane Ruiz (Damien Bonnard). The irony is immediately apparent that this nominally “anti-crime” unit, which spends much of its time harassing random black residents on the street, is really only exacerbating the problem. The film’s main inciting incident comes when Issa (Issa Perica), a boy from the projects, steals a lion cub from a Romani circus. His theft sets off a domino effect of raucous confrontations, hair-trigger police violence, digital media incriminations, and winching civic unrest, cracking racial, religious, and economic fault lines wide open in every direction across the city. Ly brings his background in documentary to bear on the proceedings, using vérité-style mobile shooting to enhance the urgency and chaos of the increasingly fractious conflicts he depicts. At its best, this febrile on-the-ground energy brings to mind the gritty docu-dramatic aesthetics and angry revolutionary politics of Gillo Pontecorvo or Costa-Gavras; at other times, the film can feel hampered by its broad characterizations and reliance on crime-narrative tropes. Still, as a snapshot of a turbulent 21st-century Western sociopolitical climate—and a sonorous reminder of the legacy of institutional oppression and precarious revolt it carries on—LES MISÉRABLES packs a solid punch. “What if voicing anger was the only way to be heard?,” rebuts a Muslim character to Ruiz’s wariness of the growing societal disorder. Ly leaves us with the same question, hanging in the middle of an internecine stalemate between a Molotov cocktail and a gun. (2019, 104 min, DCP Digital) JL

Claude Lanzmann's SHOAH (Documentary Revival)

Goethe-Institute Chicago (150 N. Michigan Ave., Ste. 200) - Monday, 10am (Free Admission)

From J. Hoberman's essay "Witness to Annihilation" (reprinted in his collection Vulgar Modernism): "People have been asking me, with a guilty curiosity I can well understand, whether SHOAH really has to be seen. A sense of moral obligation is unavoidably attached to such a film. Who knows if SHOAH is good for you? There were many times during the screening that I regarded it as a chore and yet, weeks later, I find myself still mulling over landscapes, facial expressions, vocal inflections—the very stuff of cinema—and even wanting to see it again... For, if at first, SHOAH seems porous and inflated, this is a film that expands in one's memory, its intricate cross-references and monumental form only gradually becoming apparent. One resists regarding SHOAH as art—and, as artful as it is, one should." Indeed, it seems perverse to enumerate the great formal achievements of Lanzmann's masterpiece—the jarring transitions between objective and subjective filmmaking, the astonishing close-up photography, the epic tracking shots of barren fields that force the viewer to recreate death camps in his/her imagination, and, most notably, its refusal to depict the extermination of European Jewry with any archival footage—yet they are essential to its achievement as history. Lanzmann's purposefully decentralized structure makes one feel just how enormous the atrocity of the Holocaust was. The controlled execution of millions is beyond comprehension, and certainly beyond easy summary; so the film proceeds as an accumulation of detail, none privileged above any other. In the towering mosaic of SHOAH, the testimony of a concentration camp guard assumes as much weight as a shot of a truck's rolling tires (the unforgettable final image of Part I); and, significantly, all of these things exist in the present. Lanzmann depicts the Holocaust not only in the faces of survivors, onlookers and former Nazis, but in the places these people occupy—places that, in some regard, will never disappear. From Hoberman again: "[A]lthough SHOAH is largely oral history, Lanzmann's eschewal of illustration triggers a primitive response to the photographic image. Looking at a photograph, one sees through the composition and imagines what has been pictured. Hence, Lanzmann's fanatical attention to detail; this is a film which can only unfold in the mind's eye. The question that underlies SHOAH is, how did the Holocaust happen? Lanzmann sets out to answer this both in terms of practical logistics and human sensations. How was it done, how did it feel?" (1985, 544 min, DVD on monitor) BS

Steven Spielberg’s E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL (American Revival)

Beverly Arts Center – Sunday, 2pm

Perhaps the definitive Steven Spielberg statement, E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL is a potent mix of wonderment and sentimentality. The film imagines the friendship between a grade-school boy and an affectionate space alien, advancing the optimistic message that love is truly the universal language. In his essay “Papering the Cracks,” critic Robin Wood attacked E.T. for its emotional opportunism, noting that Spielberg and screenwriter Melissa Mathison fail to characterize the title character consistently; the alien alternates between seeming wise, innocent, helpless, and godlike, depending on how the filmmakers want the audience to feel at any given moment. Yet this lack of consistency is integral to the movie’s fantasy: one reason why the character of E.T. seems so magical is because he provides what Elliot needs at exactly the right time. The alien is a playmate, a teacher, and a source of emotional support—he fills the gaps in Elliot’s broken family unit. Indeed the film derives much of its power from Spielberg’s sincere and nuanced depiction of a suburban family after a divorce. One recognizes from the opening scenes that the family is missing something and longs to be made whole. These feelings of abandonment and longing give weight to the movie’s fantasy—the wonderment comes as a source of relief. The movie is no less astute in its depiction of children, which shows the influence of François Truffaut (whom Spielberg cast in CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND). The kids of E.T. are adorable yet retain a certain realistic scrappiness—Spielberg clearly relates to his young characters, and he loves them, warts and all. (1982, 115 min, Digital Projection) BS

Greta Gerwig’s LITTLE WOMEN (New American)

Music Box Theatre – Check Venue website for showtimes

As one of literature’s greatest hits, Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women has been an endless source of identification for generations of girls. But do the four March sisters still have something to offer to modern women who live comfortably in a gender-fluid, marriage-optional world that is far removed from the types of constrictions Alcott’s characters faced? Perhaps we haven’t come as far as we think, if the considerable appeal of Greta Gerwig’s version of LITTLE WOMEN is any indicator. Gerwig has done a masterful job of scrambling the timeline of the story, beginning with Jo (Saoirse Ronan) selling her first story to a Boston newspaper, thus announcing a fresh take on the familiar story for a new generation. Gerwig creates an energetic, teeming mise-en-scène in which the sisters’ actions are much more relatable and real. Meg (Emma Watson), for example, is much less the staid and proper sister in this version, even voicing her frustration with her marriage to a man of modest means. The biggest shift Gerwig, as screenwriter, has made is moving Jo into a less commanding position and focusing more attention on Laurie (Timothée Chalamet) and Amy (Florence Pugh). I surmise this was done to play to Chalamet’s fan base, but it also downshifts the message of independence Jo has always represented to wallow in the excess of Downton Abbey-style riches. Also jarring was a Friedrich Bhaer played with a pronounced French accent by dreamy Louis Garrel, son of French director Philippe Garrel. Was the good professor Alsatian after all? And not to quibble, but could Gerwig not have found a single American actress to play the American March sisters? While Gerwig’s LITTLE WOMEN has not dislodged Gillian Armstrong’s emotionally resonant 1994 version from my heart, it is a worthy adaptation by one of our most gifted filmmakers. (2019, 134 min, 35mm) MF

MORE SCREENINGS AND EVENTS

Also at Block Cinema (Northwestern University) this week: A Night with the Shabistan Film Archive is on Friday at 7pm. The program will include two shorts and excerpts of feature films (all on 35mm film) from the Bangalore, India-based archive, with executive director David Farris and operations director (and NU professor) David Boyk in person. Screening are the short films THE MYSTERIOUS ATOM (Samiran Dutta, 1978, 11 min) and THE PINK CAMEL Paushali Ganguli, 2001, 15 min) and the first reels (approx. 20 minutes each) of the feature films SIVAJI (S. Shankar, 2007) and RAMGARTH KE SHOLAY (Adjit Dewani, 1991). Free admission.

Chicago Filmmakers (5720 N. Ridge Ave.) screens Jan Haaken’s 2018 documentary OUR BODIES OUR DOCTORS (80 min, Digital Projection) on Saturday at 7pm. Preceded by local filmmaker Andrea Raby’s 2019 short documentary UNDUE BURDENS (32 min, Digital Projection).

Also at the Gene Siskel Film Center this week: Matthew Taylor's 2019 documentary MARCEL DUCHAMP: ART OF THE POSSIBLE (90 min, DCP Digital) and Alex Gibney's 2019 UK/US documentary CITIZEN K (126 min, DCP Digital) both play for a week; Hideko Nakata's 1998 Japanese film RINGU (96 min, DCP Digital) is on Friday at 4pm and Tuesday at 6pm, with a lecture by SAIC professor Jennifer Dorothy Lee at the Tuesday screening; James Westby's 2019 documentary AT THE VIDEO STORE (72 min, DCP Digital) is on Friday at 8pm and Saturday at 5:30pm, with Westby in person at both screenings; Beniamino Barrese's 2019 Italian documentary THE DISAPPEARANCE OF MY MOTHER (94 min, DCP Digital) is on Sunday at 5pm and Wednesday at 8pm; and Juraj Herz's 1985 Czech film CAUGHT BY NIGHT [aka THE NIGHT OVERTAKE ME] (130 min, 35mm archival print) is on Saturday at 4:45pm and Thursday at 6pm.

Clayton Brown and Monica Long Ross’ 2019 documentary WE BELIEVE IN DINOSAURS (105 min, Digital Projection) is having a four-walled screening at the Gene Siskel Film Center on Monday at 6pm, with Brown and Ross in person. More info and tickets available at https://www.eventbrite.com/e/chicago-premiere-we-believe-in-dinosaurs-tickets-86735982659.

Also at Doc Films (University of Chicago) this week: Mamoru Oshii’s 1995 animated Japanese film GHOST IN THE SHELL (83 min, DCP Digital) is on Saturday at 4pm; Rian Johnson’s 2019 film KNIVES OUT (131 min, DCP Digital) is on Saturday at 7 and 9:30pm and Sunday at 4pm; Satyajit Ray’s 1984 Indian film THE HOME AND THE WORLD (140 min, DCP Digital) is on Sunday at 7pm; Richard Brooks’ 1977 film LOOKING FOR MR. GOODBAR (136 min, 35mm) in on Monday at 7pm; George Stevens’ 1956 film GIANT (201 min, DCP Digital) is on Tuesday at 7pm; and Richard Donner’s 1976 film THE OMEN (111 min, DCP Digital) is on Thursday at 9:30pm.

At the Music Box Theatre this week: Richard Stanley’s 2019 film COLOR OUT OF SPACE (110 min, DCP Digital) opens; Hiromasa Yonebayashi’s 2010 Japanese animated film THE SECRET WORLD OF ARRIETTY (95 min, DCP Digital English-dubbed version) is on Saturday and Sunday at 11:30am; Jack Henry Robbins’ 2019 film VHYES (72 min, DCP Digital) is on Friday and Saturday at Midnight; Tommy Wiseau’s 2003 film THE ROOM (99 min, 35mm) is on Friday at Midnight; and Jim Sharman’s 1975 film THE ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW (100 min, 35mm) is on Saturday at Midnight.

The Chicago Cultural Center hosts the Chicago Latino Film Festival screening of Francisco Valdez's 2014 Dominican film ONCE UPON A FISH (80 min, Video Projection) on Wednesday at 6:30pm. Free admission.

MUSEUM AND GALLERY SHOWS/EXHIBITIONS

The exhibition Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through January 26. The show features a wealth of Warhol’s short films (fifteen “Screen Tests” and other early shorts, which are all showing on 16mm), videos, and television commercials, including some very rare items. A complementary exhibit, Cinema Reinvented: Four Films by Andy Warhol, will showcase four films over the course of the Back Again show’s run, all in 16mm. Warhol’s 1967 film TIGER MORSE (34 min, 16mm) is the final film, and is on view through January 26. The film screen at the top of each hour starting at 11am.

---

The 16mm short films (1963-66, approx. 4-5 min each) showing are: ELVIS AT FERUS, JILL AND FREDDY DANCING, EDIE SEDGWICK (SCREEN TEST 308), ANN BUCHANAN (SCREEN TEST 33), PENELOPE PALMER (SCREEN TEST 255), BIBBE HANSEN (SCREEN TEST 128), NICO EATING HERSHEY BAR (SCREEN TEST 246), ME AND TAYLOR, MARIO BANANA #1, JOHN WASHING, JACK SMITH (SCREEN TEST 315), RUFUS COLLINS (SCREEN TEST 61), BILLY NAME (SCREEN TEST 194), MARCEL DUCHAMP (SCREEN TEST 80), and SALVADOR DALI (SCREEN TEST 67); and the three television commercials are: THE UNDERGROUND SUNDAE (1968, 1 min, Digital Video), CADENCE [STANDING WOMAN] (1965, 1 min, Digital Video), and CADENCE [BOTTLE] (1965, 1 min, Digital Video).

CINE-LIST: January 24 - January 30, 2020

MANAGING EDITOR // Patrick Friel

ASSOCIATE EDITORS // Ben Sachs, Kathleen Sachs, Kyle A. Westphal

CONTRIBUTORS // Cody Corrall, Marilyn Ferdinand, Jonathan Leithold-Patt