CRUCIAL LISTENING

On episode #3 of the Cine-Cast, Cine-File associate editors Ben Sachs and K.A. Westphal discuss recent releases and screenings they're looking forward to at the Chicago Film Critics Film Festival; Sachs and contributor John Dickson chat about the Philippe Garrel series at the Gene Siskel Film Center; contributor JB Mabe interviews the new Pick-Laudati Curator of Media Arts at the Block Museum of Art at Northwest University, Michael Metzger—they talk about upcoming programming and the direction Mike is taking within the Chicago film community; and contributor Kyle Cubr interviews Chicago Film Society co-founder Julian Antos about their new season.

Listen here. As always, special thanks to our producer, Andy Miles, of Transistor Chicago.

CRUCIAL VIEWING

Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s THE CHRONICLE OF ANNA MAGADALENA BACH (German Revival)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Friday, 6:15pm, Monday, 3pm, and Thursday, 6pm

There are many things one could say about Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s great 1968 film, which dramatizes the life and work of composer Johann Sebastian Bach, told primarily through the voice-over of his second wife, Anna Magdalena Bach. One could discuss Straub/Huillet’s austere formalism, which features (though not exclusively) static long-takes in medium or long shots, punctuated only occasionally by slow zooms or tracking shots in or out. One could discuss the film in the context of Straub/Huillet’s frequent practice of filming literary texts or historical subjects. One could discuss the film in its treatment of music and musical performance (which makes up the bulk of its running time). One could discuss the film as an alternate approach to the usual kind of “biopic.” One could discuss the film as a precursor to the now popular (and often too sloppily used) conception of “slow cinema.” One could do any or all of these things, and be right. But what struck me the most in seeing the film again after more than 30 years are the remarkable and dynamic shot compositions that Straub/Huillet use. Their treatment of screen space here is complex—they create a space that feels simultaneously ordered and bordering on chaos. Their articulation of space and geometry and composition is surprising and slightly unsettling. In the performance scenes, JS Bach is usually off-center, lost in the distance, lost at the edges of the frame, lost in the mise-en-scene. The shots are primarily organized along diagonals, leading the eye from right to left, or left to right, and from foreground to background. The eye becomes that active, moving agent in these otherwise mostly static shots—static in their lack or infrequent use of camera movement, editing, and activity on screen. What might at first seem overly staid or rigid is enlivened by the individual act of viewing. Contrasting these shots are occasional interstitial ones of documents—letters, music scores, administrative papers—that, ironically, feature the most overt camerawork; the camera pans across these inert objects, which accentuates their lack of depth. This is a lesson, a template, for watching all of Straub/Huillet’s films (many of which are even more minimal that this one): one must look and have the patience to look carefully and closely. Their ideas about cinema and the cinematic are so singular and so removed from easy enjoyment that a retraining of one’s viewing habits is necessary. For those willing to try, the rewards are rich indeed. (1968, 94 min, DCP Digital) PF

CFA Out of the Vault - Personal Perspectives on the Vietnam War

Chicago Filmmakers (5720 N. Ridge Ave.) and Chicago Film Archives – Saturday, 8pm

War is a name without a face, and its soldiers faces without names. That is to say, most everything about it is anonymizing, designed as such to paralyze the masses via a sort of Orwellian equivocation. The films in the “CFA Out of the Vault - Personal Perspectives on the Vietnam War” program combat this phenomenon through pointedly intimate representations of people, places and ideas pertaining to the Vietnam War. The first, 1-A (Jeffrey Lieber, Michael Sherlock and Margaret Stenberg, 1970, 8 min, 16mm), was made by Columbia College students and won an award at the 1971 Young Chicago Filmmaker’s Festival, sponsored by the Chicago Public Library; it’s a bold experimental effort that depicts a young man’s visceral response to receiving his draft card. “WILLIAM G.CLARK FOR U.S. SENATOR” (Unknown director, 1968, 1 min, 16mm) is exactly what it sounds like, an advertisement encouraging viewers to “give peace half a chance” and vote for Illinois State Senator William G. Clark for U.S. Senator. Its straightforward invocation is a far cry from today’s overcomplicated (and frequently untruthful) political ads. THE 2-YEAR MACHINE (David Alexovich, 1970, 6 min, 16mm) is another student film—this time animated and born out of the University of Illinois Chicago—that also won an award at the aforementioned festival. It’s an ingenious visualization of a standard two-year conscription, from the dreaded draft card to the resulting physical and emotional anguish. Although the film predates Schoolhouse Rock! by a few years, it nevertheless evokes that style of animation in such a way that will certainly disconcert contemporary viewers. Its sound design, likely a result of its maker’s sparse resources, is similarly discomfiting. My favorite of the bunch, 8 FLAGS FOR 99 CENTS (Chuck Olin and Joel Katz, 1970, 26 min, 16mm Preservation Print), is an extraordinary document that surveys “conservative white inhabitants of Chicago’s Garfield Ridge neighborhood” about the Vietnam War, specifically in response to President Nixon’s infamous assertion that there was a so-called silent majority of Americans who supported it. Made for the Chicago chapter of Business Executives Move for Vietnam Peace, this short documentary provides nonpareil insight into a specific demographic whose alleged silence often wasn’t so accepting—in many cases, the subjects even express sympathy for the Vietnamese people. The excerpt from Loretta Smith’s documentary A GOOD AMERICAN: THE TIMES OF RON KOVIC (1974-1998, 15-20 minute excerpt, digital projection) showcases a more outrightly radical figure, the former Marine Corp sergeant who, after being paralyzed in the war, wrote the best-selling memoir Born on the Fourth July. Though only an excerpt, it reflects Smith’s adroit use of archival footage. She'll appear in person, and if a cursory Google search is any indication, her stories will be as illuminating as the film itself. In 8 FLAGS FOR 99 CENTS, one woman says, “I think the thing that gets me the maddest is when I hear an announcer say on TV, 'Only 68 of our men were killed this week.' What do they mean, 68? That's 68 families that are torn to pieces because their boys got hit." These six films elucidate that very notion, simultaneously emphasizing the sheer immensity and devastating communion of those turbulent times. KS

Mohsen Makhmalbaf's GABBEH (Iranian Revival)

The Chicago Film Society (at Northeastern Illinois University, The Auditorium, Building E, 3701 W. Bryn Mawr Ave.) – Wednesday, 7:30pm

Mohsen Makhmalbaf is among the most inventive of all Iranian filmmakers, rich in imagination and deeply curious about the world; his best moments, like Jean Cocteau's, take advantage of his unique perspective to suggest untapped possibilities of the medium. For the uninitiated—and especially those who know Iranian cinema only for its social realism—GABBEH is an ideal introduction to his work. The film, adapted from a regional folktale, begins with a woman materializing from a tapestry (the "gabbeh" of the title) to tell an old couple her story, and the surprises keep coming from there. Makhmalbaf's narrative preserves the simplicity of traditional folklore, using it as a canvas on which to launch all sorts of formal masterstrokes. The movie is rich with editing tricks (many of which shift the story from reality to fiction), awesome location photography in the mountainous Iranian hinterlands (the film can also be appreciated as an ethnographic fantasia in the Flaherty tradition), and some of the most romantic use of color you'll ever see outside of a musical. This may lack the political orientation of Makhmalbaf's major works (MARRIAGE OF THE BLESSED, A MOMENT OF INNOCENCE), but few of his films express the joy of filmmaking as constantly as this one. Preceded by Larry Gottheim’s 1987 experimental film THE RED THREAD (17 min, 16mm). (1996, 75 min, 35mm) BS

Philippe Garrel’s L’ENFANT SECRET and THE INNER SCAR (French Revivals)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Saturday, 3pm and Tuesday, 8pm (Secret) and Saturday, 5pm and Wednesday, 8:30pm (Scar)

Often cited as the film that links Phillipe Garrel’s two modes—his early, more experimental phase associated with the near-mythical Zanzibar Group and his later, more conventionally narrative phase that’s still ongoing—L'ENFANT SECRET is indeed an elegiac blend of the methods that define his refractory career. Starring two of Robert Bresson’s “models,” Henri de Maublanc (THE DEVIL, PROBABLY) and Anne Wiazemsky (AU HASARD BALTHAZAR), L’ENFANT SECRET follows de Maublanc’s Jean-Baptiste, a film director, and his actress girlfriend, Wiazemsky’s devastating Elie, over the course of their tremulous relationship. The film’s title refers to Elie’s young son, a still image of whom penetrates the narrative at random intervals. This is but one experimental technique with which Garrel infuses the story, itself a delicate thing that evades diminution via mere summation. Allegedly based on the relationship between Garrel and former partner Nico, legendary singer and Warhol muse, the union devolves into sedate mayhem as drugs and politics come into play. Despite the implications of such drama, it’s marked by a quiet ceremony that’s complemented by Faton Cahen’s blithe score. An understated radicalism of both content and form defines Garrel’s seemingly unbalanced oeuvre, and L'ENFANT SECRET is a median amidst the paradoxes. (1979, 92 min, DCP) KS

---

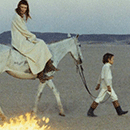

There’s an alternate universe in which THE INNER SCAR made its way onto American midnight-movie screens in the 1970s, inspiring as many endless, addled arguments about allegory and symbolism as Jodorowsky’s THE HOLY MOUNTAIN or Godard’s WEEKEND. As one takes in this entrancing 1972 psychodrama, it’s tempting to seek the logic behind Garrel’s arch-Romantic iconography and to parse the German verses exclaimed by his muse, Nico (which, per the director’s instructions, remain unsubtitled). That said, few films are as rewarding to drift away from as they are to scrutinize: seen in 35mm, it’s as easy to be transported by the divine architecture of Nico’s cheekbones and the delicate pinks and blues fringing its vast horizons as it is to be consumed by its mythological intimations. THE INNER SCAR is more a textural than textual experience, one better absorbed than comprehended: Henri Langlois lauded it as “a masterpiece for whomever does not understand German.” For all its totemic horses and talismanic stones, all you really need to “get” THE INNER SCAR can be gathered by observing the way its figures move across its otherworldly landscapes. Its paradigm is as simple as the transit of clouds: over a series of 23 sublime long-take tableaux, characters approach one another, travel together for a time across barren deserts, burning plains, and icy tundras, and then part ways. Over five decades of filmmaking, Garrel has added weight and complexity to this basic emotional template—intimacy as measured by the pain of withdrawal from someone, or the hopeless attraction one feels towards someone withdrawn into themselves. But few of his films play out so spectacularly as THE INNER SCAR, which was photographed in extreme environments in Iceland, New Mexico, Egypt, and Italy. These personal and global criss-crossings surely resemble—if you are looking for allegory—the cinematic fable of the Zanzibar Group, a blurry constellation of artists, poets, and cinéastes who assembled around radical heiress Sylvina Boissonnas during the Parisian tumult of 1968. Led by Garrel and funded by Boissonnas, the Zanzibar group worked closely, traveled widely, and lived ecstatically for two years, producing 13 films shot (mostly in lavish 35mm) across Europe, Morocco, and beyond. By the early 1970s, the group had scattered to the winds, waylaid variously by addiction, religious fervor, and, in the case of DEUX FOIS director Jackie Reynal, a career in NYC repertory film programming. Two core Zanzibar members, Daniel Pommereulle and Pierre Clementi (of LA COLLECTIONNEUSE and BELLE DE JOUR, respectively), appear, but Garrel here partakes neither of the neo-Dadaist provocations of Pommereulle’s 1969 film VITE nor the febrile 8mm kineticism of Clementi’s underground shorts. Instead, THE INNER SCAR treads an improbable line between grand Wagnerian mythopoeia and elemental austerity—a sign that the film owes as much to Nico’s voice as to Garrel’s eye. Scored to the almost liturgical strains of her 1970 masterpiece Desertshore, his innate gifts for framing, blocking, and pacing are deepened and darkened by her guttural laments. This was the first of seven cinematic monuments to Nico and Garrel’s amour fou, and it testifies to the volcanic intensity of their coming together as much as it foreshadows the agony of their separation. (1972, 60 min, 35mm) MM

Bahman Ghobadi’s NO ONE KNOWS ABOUT PERSIAN CATS (Iranian Revival)

Block Cinema (Northwestern University) – Friday, 7pm (Free Admission)

Bahman Ghobadi’s first several films, made in the Kurdish region around the Iran-Iraq border, consider the struggle of ordinary people to survive amidst warfare and harsh living conditions. His first film made in Tehran, NO ONE KNOWS ABOUT PERSIAN CATS, considers a different kind of danger in contemporary Iran. The subjects are several young musicians who want to perform western-style rock, a genre of music that’s banned under the Islamic Republic. Ghobadi shows the musicians practicing and performing in secret, as the threat of arrest is constant. (In fact the director and members of the cast were arrested twice during production of the film.) The principal characters want to play concerts in Europe, and with this desire comes a new set of challenges: they must procure visas and passports on the black market, since they cannot get them through official channels. Ghobadi intertwines their struggle to leave Iran with their daily struggle to make music, creating a sense of peril that never lets up. The songs in PERSIAN CATS provide respite from the danger as well as a sense of liberation. It’s clear why the characters continue making music in spite of the risks this carries—performing gives them (and us) the fleeting sensation of freedom within a repressive society. As usual, Ghobadi elicits humane and charismatic performances from his cast of non-professionals, not to mention an energizing sense of movement. PERSIAN CATS is always hurtling from episode to the next, and Ghobadi enlivens the musical numbers with quick-cut montages of daily life in Tehran; some of these montages present images of homeless people and illegal street vendors, reminding us that musicians aren’t the only ones who have it rough in the city. The movie feels urgent and intense, inspiring concern for the fate of the protagonists. Ghobadi will attend this screening; one hopes he’ll share stories of what happened to his cast after filming. (2009, 106 min, Digital Projection) BS

ALSO RECOMMENDED

John Carpenter's THEY LIVE (American Revival)

Block Cinema (Northwestern University) – Thursday, 7pm (Free Admission)

A defiant take on Reagan's proto-fascism, THEY LIVE is an affectionate view of working-class Los Angeles that mirrors a sincere appreciation of disreputable pop culture. Casting pro wrestler "Rowdy" Roddy Piper as the leader of a working-class insurgency is one of the most audacious choices of John Carpenter's long career, and it may be the most crystallized expression of the director's politics. Carpenter's skepticism towards contemporary life is rooted less in ideology than in a loyalty to old-fashioned genre storytelling, whose handmade qualities have been endangered by the automated culture of the corporate age. THEY LIVE famously depicts the corporate network of banks, TV stations, and multinational businesses as a secret alien plot; and while this makes for an effective sci-fi premise, it's executed too often as camp to make for effective political filmmaking. (Far more resonant are Carpenter's images of shantytowns comprised of former factory workers—a subtle reference to the collective miseries of Depression-era cinema in an era obsessed with individual success.) But, of course, Carpenter never aspired to be George Romero: His virtues lie elsewhere, in eccentric character touches, dynamic action sequences, and a consistently inventive use of the 'Scope frame. It should be noted that Carpenter was one of the few Hollywood filmmakers who insisted on shooting in widescreen throughout the VHS era, when most mainstream movies were shot in narrower ratios to be ready, like lambs to the slaughter, for panning and scanning. (1988, 93 min, 35mm) BS

Phillip Kaufman's INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS (American Revival)

Doc Films (University of Chicago) - Thursday, 10:15pm

Perhaps the most adapted of any 20th century science fiction novel, Jack Finney's The Body Snatchers has found a cinematic home no less than eight times in the past 50 years, with directors as diverse as Don Siegel and Abel Ferrara. However, no screen-interpretation of the novel has been more directly political than Phillip Kaufman's 1978 version. Set in San Francisco, Donald Sutherland plays a health inspector who becomes unwittingly involved in an alien plot to replace all humans with physically identical, though emotionally void, beings. The only way to prevent oneself from being "snatched" by the alien force is to avoid thinking or expressing any emotion. The allusions to anti-communist and anti-conformist rhetoric are less than subtle but, thanks greatly to Michael Chapman's icy cinematography and tremendous performances by Sutherland and supporting players Jeff Goldblum and Brooke Adams, Kaufman's INVASION is a haunting and striking proclamation about our desire for individuality. (1978, 108 min, 35mm) JR

70mm Shorts Program, Vol. 2

Chicago Film Society (at the Music Box Theatre) - Monday, 6pm

The Chicago Film Society follows up its stunning showcase of 70mm shorts in 2016 with a fresh batch (a personal favorite from the last iteration reappears here) for Volume 2. Featured in this collection are two trailer reels, an unidentified title from a Cinema 180 Ride, a clip from IS PARIS BURNING, a second Cinema 180 offering entitled INTERNATIONAL THRILL SHOW, a condensed version of the Russian travelogue GREAT IS MY COUNTRY (1958), TANAKH BIBELEN AL-QURAN, and the exceedingly beautiful A YEAR ALONG THE ABANDONED ROAD. Both Cinema 180 titles place the viewer aboard rides typically seen at Six Flags and amusement parks of that ilk, circa the 1970’s and 1980’s. It is a wholly vicarious experience as the camera weaves along the tracks in the front car of a rollercoaster or speeding along on Ferris wheels. These shorts would have been exhibited in said parks to allow riders with weaker stomachs to experience the thrills of rides that may have been too intense for them to experience first hand. INTERNATIONAL THRILL SHOW (1983) showcases the beauty of America by land, sea, and air. From flying through the Grand Canyon via helicopter to riding on a fan boat through the Florida Everglades to driving along the interstates of the Southeast, this delightful package of the majesty America has to offer was designed to entice German tourists to visit the United States. The long takes shown here bring a sense of grandeur to the plethora of nature available to be seen in this country. The Norwegian experimental short TANAKH BIBELEN AL-QURAN (Ole Mads Sirks Vevle, 2007) explores the texts of the Torah, Bible, and Quran. Each religious work is flipped through, page-by-page in their entirety, to provide the viewer with a sense of their respective forms and formatting. This short is not religious whatsoever but invites the viewers to come up with their own interpretation and appreciation of each text. Whether the pages are filmed left to right or right to left, their collective compositions are unified by this unique approach. A YEAR ALONG THE ABANDONED ROAD (Morten Skallerud, 1991) is a time-lapse short made over the course of a year in Børfjord, Norway, all interwoven into one shot. The beautiful cinematography works its way through the village as shifts in seasons are shown in an approachable and perceptive way while minor disturbances like rain or the constant changing from night to day are less important to the viewer. It is a stunning achievement in nature photography that must be seen on 70mm to fully appreciate. The Chicago Film Society went to great lengths importing some of this showcase’s titles and the shorts featured are some that can no longer readily be seen. The appreciation for celluloid can be felt in every frame of this carefully selected block of programming. (Various Years, approx. 90 min total, 70mm) KC

Dario Argento’s PHENOMENA (Italian Revival)

Music Box Theatre – Saturday and Sunday, 11:30am

Uncomfortable and alien, PHENOMENA was a massive departure from the furious, hallucinatory series of supernatural horrors Dario Argento had been making since 1977’s SUSPIRIA. Angry, violently colorful, and soaked with primal power, these magical films are inverted in PHENOMENA entirely. Rather than a film that peels back the viscera of the commonplace to reveal the skeleton of evil underneath, he produced a bizarre, clinical film that resists our gaze, one that grows ever more cryptic the more it progresses. At the heart of PHENOMENA is Jennifer Corvino, the daughter of a famous actor, who is sent to a mysterious Swiss boarding school for girls while her father is away on a shoot. Clever viewers might be lulled into thinking this will be a retread of the similarly-premised SUSPIRIA, but this is something entirely different, indeed almost it’s opposite. Jennifer (played expertly by Jennifer Connelly) seems to possess a psychic link with insects, and quickly makes friends with an elderly, disabled entomologist played by Donald Pleasance. As a murderer stalks the area, picking off teenage girls with abandon, Jennifer’s uncanny abilities allow her special access to the moments of death. But where an earlier Argento film would have delved into the carnal, corporeal violations, building a chromatic tapestry of gore and knife and flesh, the camerawork here is cold, dispassionate, refusing for the most part to engage with the violence within its frames. The characters, especially Jennifer, are shot as though wearing thick, hard suits of armor, and they move in eerie, inhuman ways, posturing their bodies to suggest additional joints, additional limbs. This is an insectoid horror, awash in near-monochrome, obsessively fascinated by decay and the comfortable, meatiness of death, unwilling to grant subtle psychologizing or motivations to the impenetrable interiorities of those it sees. The entomologist tells Jennifer at one point that a beetle she is holding is attempting to seduce her, that her mere presence is enough to provoke it into a premature mating season. It is a key insight into the metaphysics of PHENOMENA. The natural world is coming into its own through her. She is the gateway between the dwindling, self-important human civilization and the ever-present, marvelous wonders of the ant, the bee, the fly, beetle, who see all, reveal so little, and wait with infinite patience for us to kill ourselves off. Nota Bene: the film is showing in a significantly shortened (and re-titled CREEPERS), 82-minute version (from its original 116 minutes) that this critic has not seen. (1985, 82 min U.S. release version, 35mm) KB

Göran Hugo Olsson’s THAT SUMMER (New Documentary)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Check Venue website for showtimes

An alternate title for THAT SUMMER, this elegiac and nostalgic documentary, could be September Song, after the lovely Kurt Weill and Maxwell Anderson standard. The film evokes the season of dwindling, precious days, as much as the ones when life's in full bloom. The news about the movie, directed by Göran Hugo Olsson (THE BLACK POWER MIXTAPE 1967-1975), is that it unearths four reels of film, lost for 45 years, from the original, June '72 attempt to make a film about the legendary Beales, first seen in the Maysles brothers' 1975 cult-classic documentary GREY GARDENS. Presumably, most readers know the outline of the story of Edith and Edie Bouvier Beale, Jackie Kennedy Onassis's aging aunt and cousin, respectively, and can conjure up images of Little Edie in her turban, crooning the likes of Spring Will Be a Little Late, immune to the squalor, performing for the camera, her mother, and their gallery of raccoons and cats. And so once more we revisit their "strange and wonderful world." That affectionate description comes from photographer and collage artist Peter Beard, who spent the summer of '72 with Lee Radziwill, Jackie O's sister, on Skorpios, Aristotle Onassis's Greek island, and in Montauk, the hamlet on the edge of Long Island where he still lives today. It became an artists' colony. Andy Warhol's Factory people hung out there, everyone filming each other. (It's rather comical to see Warhol on the beach, looking game, if a bit uncomfortable.) THAT SUMMER combines the lost Beales footage with what are essentially home movies, albeit gorgeously expressive ones, taken by Warhol, Jonas Mekas, Vincent Fremont, and Beard, of life at Montauk. From there, Beard and Radziwill could easily drive over to visit her relatives, Edith and Edie, who were in the news for being harassed by East Hampton town officials and the Suffolk County Health Department. The idea, Radziwill says, was to make a film wherein her "extremely eccentric" aunt, Big Edie, would narrate Radziwill's memories of Old East Hampton, which she'd loved as a child. The unearthed footage, some of it shot by Albert Maysles, also records the efforts, bankrolled by Jackie and Ari, to save Grey Gardens by bringing it up to code. I'm endlessly tickled by the Beales. They were not mentally ill. They were dotty—charismatic Edie flirting with the lens, perpetually ready for her closeup. They were in the tradition of great American characters like Thoreau, eccentrics living their own way, which brought out, in others, the equally American tradition of enforced conformism. They remind me of people in my own life, people I miss. There is a moving, circular symmetry to THAT SUMMER which exquisitely enhances the Beales' story's themes, of memory and fading, crumbling beauty. The Beales show us old photographs, and we see how beautiful they were in their youths. Today, Beard and Radziwill are at the stage of life Edith was then. In the summer of '72, though, they were young and beautiful and strong and happy. There's a danger in nostalgia, sometimes: the idea that things were better then, and that changes are inherently sad. And yet, as Radziwill, who's 85 today, puts it, "Without memory, there's no life." And it's hard not to lament, with Beard, how "it's all about money, now," or to argue with him that the summer of '72 was, as he puts it, "perfect," or that maybe the world is a less weird place for the Beales being gone. This may be the last time we see them, after all. We come away from THAT SUMMER with a renewed sense of what a pity it would be if there were no places left for the mad ones and the dreamers, to live they way they wish. As the film ends, a title tells us that Grey Gardens was recently up for sale, for $18 million. (2017, 80 min, DCP Digital) SP

Kenji Mizoguchi's SANSHO THE BAILIFF (Japanese Revival)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Friday, 2pm, Sunday, 3pm, Monday, 5pm, and Wednesday, 6pm

An epic of lost innocence about a good-hearted family whose members are separated and sold into prostitution and slavery, SANSHO THE BAILIFF is Kenji Mizoguchi’s most emotionally exacting and profoundly haunting achievement. Set in eleventh-century Japan, but shot through with tensions and crises of identity specific to the post-occupation period, SANSHO uses an old story, “one of the world’s great folk tales, full of grief,” to work through postwar Japan’s reluctant recognition of its own crimes committed against humanity during WWII, alongside its accelerating adoption of Western democratic values. The title character of the film, a corrupt bailiff with direct ties to the imperial government, is a figure we only rarely glimpse on-screen, and yet whose amoral, predatory worldview is fully, oppressively realized in nearly every frame; he is the character who stands in for the merciless social world and its relations. Politics is central to the story of SANSHO, and the film invokes human rights as well as the very real, difficult struggle to actually achieve it in the world. If the film’s insistent refrain—“Without mercy, man is like a beast...Men are created equal. Everyone is entitled to happiness”—sounds acutely anachronistic to the eleventh century, it is because Mizoguchi’s much more likely referent was the UN’s 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (which this dialogue could almost have been lifted from directly). But I think the most compelling anachronism in SANSHO remains legendary composer Fumio Hayasaka’s unforgettably strange, untidy, lingering score, which disruptively pairs Western orchestral elements with Japanese period instruments, creating some striking atonalities and modernist effects. The sound mix in SANSHO is a special realm where elements of the supernatural, ineffable, and transcendent enter, sometimes imperceptibly, into the otherwise punishing realism of Mizoguchi’s image. Continuing his experiments (begun in his 1950 and 1953 scores for Kurosawa’s RASHOMON and Mizoguchi’s UGETSU) in transposing Japanese theater music to Western symphonic orchestration, Hayasaka’s score for SANSHO disruptively pairs traditional instruments such as the komabue (a bamboo flute traditional to Japanese court music) and the staccato plucking of a biwa (a short-necked fretted lute) with ethereal celeste glissandos, harp arpeggios, and other Western elements. The finished effect that we hear is rarely of a harmonic, hierarchical system, but rather of a kind of parallel scoring, as if the film had been scored by Hayasaka not once but twice, with East and West refusing to meet—the instruments from the two traditions are as if exiled to separate tracks, often seemingly unaware of each other and working at cross-purposes, creating a dissonance that is only (partially) resolved by the film’s final shot. The strangeness of this scoring suits the allegorical dimension of SANSHO tremendously, always seeming to gesture to an ethical realm that exists apart from the densely physical world in which our characters suffer. The clash of musical traditions is ambitious and hair-raising, but Mizoguchi’s film leaves room too for the grand emotional power that builds in the desperation of a mother’s voice, calling her children home. (1954, 125 min, DCP Digital) TTJ

Kenji Mizoguchi's A STORY FROM CHIKAMATSU [aka CRUCIFIED LOVERS] (Japanese Revival)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Friday, 4:15pm, Saturday, 3pm, Sunday, 5:30pm, and Tuesday, 6pm

For many years, the Western title of Mizoguchi's CHIKAMATSU MONOGATARI was THE CRUCIFIED LOVERS, a less obscure and more exploitation-friendly marquee, less a spoiler than a premonition. The decision, some sixty years later, to revert to the more accurate translation of A STORY FROM CHIKAMATSU also restores to Mizoguchi's art a certain sheen of heritage filmmaking that purely formalist interpretations often miss. (Similarly, what we know as THE LIFE OF OHARU translates literally as THE LIFE OF A WOMAN ACCORDING TO SAIKAKU.) Watch the original Japanese teaser trailer for CHIKAMATSU, and you'll see the cast frolicking amidst lion tchotchkes from the Viennale, site of Mizoguchi's three consecutive international triumphs. Clearly, the director is the pride of Daiei, and of the whole Japanese film industry, a filmmaker who brings a 'modern touch' to literary classics and elevates them to the world stage, a key figurehead in the country's post-war revival. In that context, CHIKAMATSU plays as a bewildered excavation of feudal psychology, the dusting-off of a classic that resonates precisely because it's so resolutely grounded in familiar abuses of the office, the home, and the marital bed. It's also, of course, one of Mizoguchi's most beautifully judged films, the claustrophobic confines of the boss's house effortlessly contrasted with the unfettered expanse of the natural world. The distinction is subtle: the interiors are subject to constant reframing, with the camera jerked on its axis to find a better view of a conversation behind a doorway while the camera crane follows the fugitive lovers over the hills. CHIKAMATSU stands besides other Mizoguchi works in its slashing anger towards a society that refuses to let souls rise above their circumstance, but in the end, it becomes that rarest of things: a smiling tragedy. (1954, 102 min, DCP Digital) KAW

Bong Joon-ho’s MEMORIES OF MURDER (South Korean Revival)

Doc Films (University of Chicago) – Sunday, 7pm

With his second feature, MEMORIES OF MURDER, Bong Joon-ho established himself as one of the most gifted filmmakers of the Korean New Wave. The film is funny, suspenseful, and subversive, raising questions about the police’s use of force. It also anticipates David Fincher’s ZODIAC in its narrative structure, which was based on a real police investigation of a series of unsolved murders. Like ZODIAC, the film generates fascination through the careful accumulation of clues and investigative techniques, but thwarts the audience’s desire for catharsis by leaving the mystery open-ended. Set in the mid-1980s, MURDER takes place in a small town where a few women have been raped and killed in an especially grisly fashion. The local police, led by Song Kang-ho’s incompetent but lovable detective, begin to investigate, but they interrogate the wrong suspect time and time again. (They also exploit the brutality of the crimes to torture their suspects, which Bong plays for dark political satire—we’re reminded that the investigation coincides with the South Korean government’s crackdown on protesters throughout the country.) Enter Detective Seo (Kim Sang-kyung), who arrives from Seoul to help with the investigation. He’s clearly smarter than his small-town counterparts—which creates tension and no small amount of humor—though he too ends up flummoxed by the mystery. Bong’s style is graceful but tough; the camera movements are impressive, but you may not recognize that because the storytelling is so compelling and the details so lurid. The film culminates with a series of despairing sequences that call the entire investigation into question, elevating this policier into the realm of existential tragedy. (2003, 132 min, DCP Digital) BS

Sam Wood's A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (American Revival)

Doc Films (University of Chicago) – Friday, 7 and 9:30pm and Sunday, 1:30pm

The most famously inconsistent movie ever made, the Marx Brothers' first vehicle at MGM alternates some of their most beloved comic set pieces with a dreadful love story done entirely straight. While there's plenty of superfluous plot in THE COCOANUTS (1929) or MONKEY BUSINESS (1931), the Brothers were free to walk all over it in those films, stepping in front of the speaking players, throwing props and the like while the rest of the cast carries on as though nothing was wrong. These moments still feel liberating because they remind us how arbitrarily rules are assigned to entertainment; anyone with enough chutzpah, the Paramount movies imply, can reinvent them as they please. (This idea would lay the foundation for Jacques Rivette's CELINE AND JULIE GO BOATING [1973], though Rivette would lack the Marx Brothers' genius timing.) Comic anarchy safely isolated from the narrative, the Brothers seem as though in captivity, but there are still enough sidesplitting moments to make this worthwhile, especially in a crowded theater. (1935, 96 min, 35mm) BS

Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (British/American Revival) [70mm]

Music Box Theatre – Check Venue website for showtimes

For many, 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY is not simply a masterpiece, but the apotheosis of moviegoing itself. In no other film is the experience of seeing images larger than oneself linked so directly to contemplating humanity's place in the universe. Kubrick achieves this (literally) awesome effect through a number of staggering devices: a narrative structure that begins at "the dawn of man" and ends with the final evolution of humankind; one-of-a-kind special effects, the result of years of scientific research, that forever changed visual representations of outer space; a singular irony that renders the most familiar human interaction beguiling; blasts of symphonic music that heighten the project of sensory overload. It isn't hyperbolic to assert, as film scholar Michel Chion has in his book Kubrick's Cinema Odyssey, that this could be the most expensive experimental film ever made; it's certainly the most abstracted of all big-budget productions. As in most of Kubrick's films, the pervasive ambiguity—the product of every detail having been realized so thoroughly as to seem independent of an author—ensures a different experience from viewing to viewing. Much criticism has noted the shifting nature of "thinking" computer HAL-9000, the "star" of the movie's longest section, who can seem evil, pathetic, or divine depending on one's orientation to the film; less often discussed is the poker-faced second movement, largely set in the ultra-professional meeting rooms of an orbiting space station. Is this a satire of Cold War diplomacy (something like a drier follow-up to DR. STRANGELOVE)? An allegory about the limitations of scientific knowledge? Like the "Beyond the Infinite" sequence that makes up most of the film's final movement—an astonishing piece of abstract expressionist art every bit the equal of the Gyorgy Ligeti composition that accompanies it—one can never know concretely what it all "means," nor would one ever want to. (1968, 142 min, 70mm; Brand New Print) BS

Claire Denis’ LET THE SUNSHINE IN (New French)

Music Box Theatre – Check venue website for showtimes

Claire Denis follows up her darkest and most disturbing feature, 2013’s BASTARDS—a gut-wrenching journey into the heart of a prostitution ring that was loosely inspired by William Faulkner—with LET THE SUNSHINE IN, undoubtedly her lightest and funniest work, which was loosely inspired by Roland Barthes. A delight from start to finish, Denis’ first collaboration with the iconic Juliette Binoche is probably the closest we’ll ever come to seeing the Gallic master’s take on the rom-com. Binoche, looking more radiant than ever at 53, plays Isabelle, a divorced mother living in Paris whose career as a painter is as successful as her love life is a mess. The neurotic Isabelle plunges headfirst into a series of affairs with dubious men, some of whom are married and one of whom is her ex-husband, all the while hoping to find “true love at last.” Isabelle’s best prospect seems to be the only man who wants to take things slow (Alex Descas) but a witty coda involving a fortune-teller played by Gerard Depardieu suggests that Isabelle is doomed to repeat the same mistakes even while remaining a hopelessly optimistic romantic. Bolstered by Agnes Godard’s tactile cinematography and Stuart Staples’ fine jazz score, LET THE SUNSHINE IN is funny, wise, sexy—and essential viewing. (2017, 94 min, DCP Digital) MGS

MORE SCREENINGS AND EVENTS

The Film Studies Center (at the Logan Center for the Arts, 915 E. 60th St., University of Chicago) presents Cats, Bats, Rats, and Roses: Films for Spring Fever (approx. 80 min total, 16mm and Digital Projection) on Friday at 7pm. Screening are BROKEN NEW: DISASTER (Lori Felker, 2012, Digital Projection), ECHOES OF BATS AND MEN (Jo Dery, 2005, 16mm), ALL MY LIFE (Bruce Baillie, 1966, 16mm), RAT LIFE AND DIET IN NORTH AMERICA (Joyce Wieland, 1968, 1968), WALK FOR WALK (Amy Lockhart, 2005, 16mm), RICKY AND ROCKY (Tom Palazzolo and Jeff Kreines, 1972, 16mm), MOUND (Allison Schulnik, 2011, Digital Projection), PONIES PONIES PONIES (Lisa Barcy, Unconfirmed Year, Digital Projection), SPOOKY BOO’S AND ROOM NOODLES (JP Somersaulter and Lillian Somersaulter-Moats, 1976, Digital Projection), AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (1941 or 1945, 16mm), and RO-REVUS TALKS ABOUT WORMS (1971, South Carolina ETV, DVD Projection). Free admission.

Also at Chicago Filmmakers (5720 N. Ridge Ave.) this week: Jen Heck’s 2016 documentary THE PROMISED BAND (89 min, Blu-Ray Projection) is on Sunday at 7pm. Preceded by Jessie Ewing's 2017 documentary I’M HERE TO STAY (10 min, Digital Projection).

The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago presents Chicagoland Shorts Vol. 4 on Tuesday at 6pm. Screening are: THE LINGERIE SHOW (Laura Harrison), THE MAGIC HEDGE (Frédéric Moffet), SOLAR PULSE (Dena Springer), 4 THINGS TO REMEMBER (Hannah Kim), EVERY GHOST HAS AN ORCHESTRA (Shayna Connelly), AND YOU THE BELL (Elisabeth Hogeman), SOMETHING TO MOVE IN (Latham Zearfoss), VERACITY (Seith Mann), and ON THE RINK (Benjamin Buxton). Free admission, but RSVPs required at the MCA’s website.

Cinema 53 screens Olivier Babinet's 2016 French film SWAGGER (84 min, Video Projection) on Thursday at 7pm at the Harper Theater (5238 S. Harper Ave.). Free admission.

The Goethe-Institut Chicago (150 N. Michigan Ave., Ste. 200) screens Alexander Kluge’s mammoth 2008 documentary film NEWS FROM IDEOLOGICAL ANTIQUITY – MARX/EISENSTEIN/THE CAPITAL (570 min, Video Projection) on Thursday at 10am. Free admission.

South Side Projections presents Stories We Tell: Cuban Short Animations and Fictions, 1961-2017 (approx. 60 min, Video Projection) on Wednesday at 7pm at La Catrina Café (1011 W. 18th St.). Followed by a conversation between Americas Media Initiative Director Alexandra Halkin and University of Chicago graduate student Pedro Noel Doreste. Screening are: EL COWBOY (Jesús de Armas, 1961, 8 min), THE POET AND THE DOLL (El poeta y la Muñeca) (Tulio Raggi, 1967, 6 min), ANOTHER ANIMATION NOT FOR KIDS (Otro animado no para niños) (Harold Díaz-Guzmán Casañas, 2013, 6 min), WELCOME TO HEAVEN (Bienvenidos al cielo) (Marcos Menendez, 2012, 3 min), DAMN CIRCUMSTANCES (La Maldita Circunstancia) (Eduardo Emil, 2002, 10 min), RING, RING (Tiln, Tiln) (Violena Ampudia, 2017, 3 min), and FILIBERTO (Amanda Garcia, 2008, 11 min). Free admission.

The Nightingale Cinema (1084 N. Milwaukee Ave.) hosts a program presented by Northwestern University’s Department of Art Theory and Practice on Saturday at 7pm. The screening, titled We Need To Hide What We’re Doing, features work by the department’s students, alumni, and staff. Free admission.

The Instituto Cervantes (31 W. Ohio St.) screens Gabylu Lara's 2018 Mexican film AMERICAN CURIOUS (85 min, DVD Projection) on Wednesday at 7pm. Free admission.

The Spertus Institute presents episodes one and two of the Israeli television series Shtisel (2013, 90 min total, Video Projection; directed by Alon Zingman) at the Mayer Kaplan JCC (5050 Church St., Skokie) on Tuesday at 7pm. Followed by a discussion.

Black Cinema House (at the Stony Island Arts Bank, 6760 S. Stony Island Ave.) presents Jumaane Taylor: A Cinematic Tap Experience on Friday at 7:30pm. The event features a screening of George T. Nierenberg’s 1985 documentary ABOUT TAP (28 min, Video Projection) and a performance by dancer Jumaane Taylor. Free admission.

The Italian Cultural Institute (500 N. Michigan Ave.) screens Luigi Lo Cascio’s 2012 Italian film THE IDEAL CITY (105 min) on Saturday at 6pm, with Lo Cascio in person; and Clothes vs. Costumes, a lecture by costume designer Anna Lombardi, on Tuesday at 6pm. Both free admission.

At the Northbrook Public Library (1201 Cedar Lane, Northbrook) this week: Jerry Zucker’s 1990 film GHOST (127 min, 35mm) is on Wednesday at 1 and 7pm. Free admission. www.northbrook.info

Also at the Gene Siskel Film Center this week: Laurent Cantet’s 2017 French film THE WORKSHOP (113 min, DCP Digital) plays for a week; and Abbie Reese’s 2017 documentary CHOSEN: CUSTODY OF THE EYES (107 min, DCP Digital; all screenings open captioned) is on Friday at 8:15pm, Saturday at 5pm, Sunday at 7:30pm, and Thursday at 8pm, with Reese in person at all shows.

Also at Doc Films (University of Chicago) this week: Sebastián Lelio’s 2017 Chilean film A FANTASTIC WOMAN (104 min, DCP Digital) is on Saturday at 7 and 9:30pm and Sunday at 4pm; Elia Kazan’s 1976 film THE LAST TYCOON (123 min, DCP Digital) is on Wednesday at 7 and 9:30pm; and Philip Kaufman’s 1988 film THE UNBEARABLE LIGHTNESS OF BEING (171 min, 35mm) is on Thursday at 7pm

Also at the Music Box Theatre this week: Xavier Beauvois’ 2017 French film THE GUARDIANS (138 min, DCP Digital) opens; Jeremy Dyson and Andy Nyman’s 2017 film GHOST STORIES (97 min, DCP Digital) is on Friday and Saturday at 11:45pm; Robert McGinley’s 2017 film DANGER DIVA (99 min, DCP Digital) is on Monday at 5pm; and Justin MacGregor’s 2018 film BEST F(R)IENDS: VOLUME 1 (102 min, DCP Digital) is on Thursday at 7:30pm, with writer and star Greg Sestero in person; Note: Lana and Karin Wachowski’s Sense8 Final Episode (2018, 151 min, DCP Digital) on Friday at 7pm is Sold Out.

Facets Cinémathèque plays Erika Cohn’s 2017 Palestinian/US documentary THE JUDGE (76 min, Video Projection) for week-long run.

Comfort Film at Comfort Station Logan Square (2579 N. Milwaukee Ave.) presents Released and Abandoned: VHS Trailer-a-rama (Unconfirmed Running Time, VHS Projection) on Wednesday at 8pm. Free admission.

The Chicago Cultural Center hosts the Cinema/Chicago screening of Jörg A. Hoppe, Heiko Lange, Klaus Maeck, and Miriam Dehne’s 2014 documentary B-MOVIE: LUST & SOUND IN WEST BERLIN (92 min, Video Projection) on Wednesday. Introduced by Northwestern University professor Rob Ryder. Free admission.

ONGOING FILM/VIDEO INSTALLATIONS

Currently on view at the Art Institute of Chicago: Cauleen Smith's single-channel video SPACE IS THE PLACE (A MARCH FOR SUN RA) (2001) is in the Stone Gallery; Gretchen Bender's eight-channel video installation TOTAL RECALL (1987) is in Gallery 289; Joan Jonas’ MIRROR PIECES INSTALLATION II (1969/2014) is in Gallery 293B; Frances Stark’s 2010 video installation NOTHING IS ENOUGH (14 min loop) in Gallery 295C; and Nam June Paik’s 1986 video sculpture FAMILY OF ROBOT: BABY in Gallery 288.

CINE-LIST: May 25 - May 31, 2018

MANAGING EDITOR // Patrick Friel

ASSOCIATE EDITORS // Ben Sachs, Kathleen Sachs, Kyle A. Westphal

CONTRIBUTORS // Kian Bergstrom, Rob Christopher, Kyle Cubr, Tien-Tien Jong, Michael Metzger, Scott Pfeiffer, Joe Rubin, Michael Glover Smith