CRUCIAL VIEWING

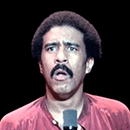

Jeff Margolis’ RICHARD PRYOR: LIVE IN CONCERT (American Revival)

Music Box Theatre – Tuesday, 7:30pm

A little after recovering from a heart attack and being arrested for shooting his wife’s car with a .357 magnum and a little before setting himself on fire while freebasing, Richard Pryor delivered what is surely one of the greatest stand-up comedy performances in the history of the form. The pinnacle of the show is his discussion of his beloved spider monkeys, which, if he opened their cage, would run up his arm and attempt intercourse with his ear. The segment demonstrates Pryor’s subtle blend of raunchy humor, brilliant storytelling, masterful pacing, and genuine emotion. Jeff Margolis, the credited director, is a veteran of shooting live events and knows to capture what’s happening on stage and otherwise stay out of the way. Digital releases of the film have been wretched: Pryor’s hair tends to disappear against the dark background when he’s standing still, and trailing ghost images of his face and shirt follow his every move. Here’s your chance to see this on 35mm as God intended. Part of the Music Box’s “Is It Still Funny?” series. Mark Caro will introduce the film and lead a post-screening discussion. (1979, 78 min., Archival 35mm Print) MWP

Andrzej Żuławski’s L'IMPORTANT C'EST D'AIMER (French Revival)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Friday, 8:15pm, Saturday, 7:45pm, Sunday, 5:15pm and Wednesday, 8:15pm

“What can one say for such a fiasco?...Excessive, dark, over the top. Expressionistic without reason, his directing is a mishmash of contradicting intentions and random ideas to the point of which the only point is chaos.” A review of an Andrzej Żuławski film, or a play featured in an Andrzej Żuławski film? Officially the latter, but it could very well be the former, all things—all muddled and tumultuous things—considered. And that’s not so bad, as is exemplified in the Polish director’s third feature film, L'IMPORTANT C'EST D'AIMER, which he made in France after being exiled from Poland following his controversial film, THE DEVIL. It stars Romy Schneider as a soft-core porn actress, Nadine, whose alluring vulnerability during a particularly grotesque shoot entrances an on-set photographer; she laments that she must resort to such dreck, having once aspired to be a serious actress. The photographer, Servais, borrows $10,000 from his shady boss so that he may finance an avant-garde production of Shakespeare’s Richard III, the only condition being that Nadine gets a starring role opposite Klaus Kinski’s eccentric leading man. So what’s keeping them apart? Nadine’s charmingly sciolistic husband, Jacques (played by French music star Jacques Dutronc), who is obsessed with photographs of old Hollywood actors. As with any Żuławski film, the relative straightforwardness of its synopsis is misleading; dizzying camera movements, caricatural aesthetics, and a melodramatic score by Georges Delerue transform a banal story, that of tortured artists and an all-consuming love triangle, with near operatic excess. Its English title is THE MOST IMPORTANT THING: LOVE, another simplification of a deliberately overwrought realization. Still, it’s not entirely unsuitable—Żuławski’s mélange of cinematic indulgences ultimately yields something substratal in its guilelessness, a testament to his madcap auteurism. (1975, 109 min, DCP Digital) KS

Shyam Benegal’s NISHANT (Indian Revival)

Block Cinema (Northwestern University) – Friday, 7pm (Free Admission)

Indian critics tend to cite Shyam Benegal as one of the most important Indian directors of the 1970s and cite NISHANT in particular as one of the key films of its era. It’s an incendiary attack on the legacy of feudalism in modern Indian backwaters, presenting a terrifying portrait of corruption in a small village. The primary characters are a wealthy, landowning family who live as though above the law. In the film’s most upsetting episode, two grown brothers in the family abduct the wife of an upstanding schoolteacher because their younger brother desires the woman. The schoolteacher’s efforts to get back his wife, which are constantly thwarted, occupy the remainder of the story; NISHANT is excruciating to watch, but it inspires rage like few other films do. Benegal, working from a script by noted playwright Vijay Tendulkar, indicts not only the wealthy family but also the poor townspeople who are complacent in the family’s corruption. The cast includes several mainstays of “Parallel Cinema,” the Indian filmmaking movement that arose in the 1960s and 70s to forge an artistic path distinct from both Bollywood and European movies: Shabana Azmi, Amrish Puri, Girish Karnad, and Naseeruddin Shah. (1975, 140 min, Unconfirmed Format) BS

David France’s THE DEATH AND LIFE OF MARSHA P. JOHNSON (New Documentary)

Reeling Film Festival (at Landmark's Century Centre Cinema) – Saturday, 12:15pm

A more apt title for David France’s (HOW TO SURVIVE A PLAGUE) new documentary would be “The Death of Marsha P. Johnson and Life of a Community Left to Cope.” Admittedly a bit ponderous, but it suggests France’s associative approach to telling not just the story of Johnson, but that of the New York trans community living on a knife-edge through the decades. Johnson was an African American trans woman, a gay liberation activist and co-founder of S.T.A.R. (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), and was frequently associated with the 1969 Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village. She was a pillar of the West Village community but in the summer of 1992 her body was found floating in the Hudson River. Her death was quickly deemed a suicide by the 6th Precinct despite the misgivings of those that knew her best. THE DEATH AND LIFE OF MARSHA P. JOHNSON is not a traditional biopic though, and Johnson serves more as a rallying point. The real stars are Victoria Cruz, the audience surrogate and a Jedi-like figure perpetually wrapped in black wandering the streets of present day Manhattan attempting to solve Johnson’s death, and the late co-founder of S.T.A.R., Sylvia Rivera. Rivera looms especially large in THE DEATH AND LIFE, as her rise, fall, and return to the fold is documented in devastating archival footage, which occasionally threatens to eclipse everything around it. One scene recorded by a news crew in the mid-90s finds Rivera in a homeless camp about to be cleared for construction on the banks of the Hudson. When she declares to the camera, “Yeah I’m crazy because the world has made me crazy,” you feel at once that you truly understand her, and deeply implicated by your own past snap judgments. Of course THE DEATH AND LIFE evokes a sense of anger and righteous indignation. Out of the movie and into the streets, if you wish. But what makes the work so successful is that your first impulse is toward heartbreak, which France invites you to sit in and feel without reprieve. (2017, 105 min, DCP Digital) JS

---

Reeling: The Chicago LGBTQ+ International Film Festival continues through Thursday, with seven days of features and shorts programs at the Landmark’s Century Centre Cinema. Full schedule at www.reelingfilmfestival.org.

ALSO RECOMMENDED

Stuart Gordon’s RE-ANIMATOR (American Horror Revival)

Music Box Theatre – Check Venue website for showtimes

Of all the H.P. Lovecraft works director Stuart Gordon has adapted to film, RE-ANIMATOR endures as his magnum opus. The idea to create this film came to Gordon after discussing vampire movies with a friend and determining that there were too many Draculas and not enough Frankensteins. At Miskatonic University, headstrong med student Herbert West (Jeffrey Combs) has recently arrived to continue research on his serum that can re-animate recently deceased bodies. He becomes roommate with fellow classmate Dan (Bruce Abbott) who is dating Megan, the daughter of the Dean. As Herbert’s experiments progress, unintended side effects ensue that throw him, Dan, and the entire medical school of Miskatonic into danger’s way. The practical effects used are one of the key components that make this film work so well; disembodied heads, a psychotic cat, and gory dismemberment are all featured to great effect. Composer Richard Band cited Bernard Herrmann’s score for PSYCHO as his main influence for the film’s distinctive soundtrack, maintaining a staccato-ed and string-heavy nature. Like many other horror films of its era, the film uses slapstick horror to lighten the tone, with several sequences in the morgue being particularly funny. RE-ANIMATOR is a slice of pure 80’s B-movie fun and remains one of the finest adaptations of H.P. Lovecraft’s work. (1985, 105 min, 35mm/DCP Digital) KC

---

Note that a 35mm print will be screening for the 9:45pm shows on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday; all other screenings are DCP Digital.

---

More info at www.musicboxtheatre.com

Jean-Pierre Dardenne and Luc Dardenne's THE UNKNOWN GIRL (New Belgian)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Check Venue website for showtimes

The Dardenne Brothers return with this expressive, visceral realist mystery. Adèle Haenel gives a naturalistic central performance as a promising young doctor at a working-class clinic on the outskirts of the Belgian riverside city of Liège. She's admired, even beloved. One fateful evening after a long day, she refuses to let her intern buzz someone in after hours. When the night caller turns up dead, she feels responsible. If she'd given the desperate African woman shelter, she'd be alive—a powerful, relevant metaphor. Mounting an investigation to discover the unknown woman's name, she discovers secrets involving the young son of her own patients, as well as various more or less threatening characters. (The boy's father is played by Dardennes regular Jérémie Renier). The Dardennes' mise en scène, carefully composed yet open, is rendered in the fluid handheld style of their longtime cinematographer, the great Alain Marcoen. Actors, directors, cameraman: all seem to be in a process of mutual discovery, catching real life as it unfolds. There's something in the doctor's steadfast, non-judgmental acceptance of people as they are, the way she even shares in their guilt, that makes one unforgettable scene in particular play out very differently than it might have. This movie has no score to telegraph how we're meant to feel. There's just one person caring, helping...because that's what she does. (2016, 106 min, DCP Digital) SP

Krzysztof Kieslowski’s BLIND CHANCE (Polish Revival)

Doc Films (University of Chicago) – Tuesday, 7pm

BLIND CHANCE is a crucial work in Krzysztof Kieslowski’s filmography, expanding on the political themes of his 1970s films with the metaphysical themes that would define his films from DEKALOG to the Three Colors trilogy. It’s also the most entertaining Polish film of its era, exhibiting a mix of showmanship and formal mastery that recalls the best of Hitchcock. Kieslowski is having great fun here, playing with time and space, and the film invites us to have fun with him. The ingenious script tells three variations on the same story, which begins when a young man named Witek (a well-intentioned but naive intellectual straight out of the films of Kieslowski’s mentor, Krzysztof Zanussi) races to catch a train. Kieslowski imagines what might happen to Witek if he catches the train, then what happens if he doesn’t, and then if he doesn’t catch the train in a different manner. In the first story, Witek befriends a Communist official he meets on the train and enters into a career in the Party. In the second, he gets stuck doing community service (for reasons too complicated to explain here), falls in with a group of activists, and ends up protesting the State. In the third, Witek ignores politics altogether, returns to medical school, and finds the love of his life. Kieslowski uses cinema as Hitchcock did, to grant small objects and gestures a monumental importance and generate tremendous suspense in the process. (Indeed the scenes of Witek running through the train station are some of the most suspenseful sequences ever filmed.) The narrative turns are exciting—you’re always trying to spot what little thing will change Witek’s life this time—and they’re ripe with Polish irony. BLIND CHANCE tells a grand, bitter joke: no matter which way Witek goes, he always ends up in the same place. The Polish government didn’t appreciate this joke, which reflects the general disillusionment that Poles felt toward their government in 1981, and it banned BLIND CHANCE for six years. Communist Poland ended, but the film lived on, inspiring at least one enjoyable knock-off (Tom Tykwer’s RUN LOLA RUN) and drawing decent-sized audiences whenever it’s revived. Today, its political anger is less impressive than Kieslowski’s wonderful curiosity about fate, choice, and other factors that shape human experience. (1981, 123 min, DCP Digital) BS

Arturo Ripstein's TIME TO DIE (Mexican Revival)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Saturday, 5:45pm and Wednesday, 6pm

One of many interesting things about Arturo Ripstein's Mexican Western TIME TO DIE is just how much it plays like an American Western, making you think once again about how very arbitrary that border between Mexico and the U.S. really is. Still, for many the hook for this memorable low-budget movie will be its literary pedigree: Gabriel García Márquez, the esteemed Columbian man of letters, wrote the movie's story, then adapted it into a screenplay with no less than Carlos Fuentes, the great Mexican novelist. TIME TO DIE, now restored by Film Movement for its 50th anniversary, is also the debut feature of Mexican auteur Ripstein (BLEAK STREET, THE CASTLE OF PURITY, DEEP CRIMSON), who got his start as a protégé to Buñuel, visiting the set of THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL to learn at the feet of the master. After 18 years away in prison for killing a man, an honorable man (Jorge Martínez de Hoyos) comes back to his little town. He's paunchy now, in his 40s, and gentle. Once, however, he was considered "bulletproof," "the best with women, horses and pistols—a real man." (The movie's a subversion of this kind of machismo.) He doesn't realize the two sons of the dead man, a bad egg he killed fair and square in a duel, still want to kill him, particularly the vengeful older brother (Alfredo Leal). He befriends the kind younger brother (Enrique Rocha), whose girlfriend (Blanca Sánchez) does her best to forestall the inevitable. She takes counsel from the bitter experience of her older friend (Marga López), who, all those years ago, was the "killer's" fiancée. He just wants to knit and live out his days quietly with the woman he still loves. Soon enough, however, he's suiting up to repeat the past, putting on the same vest he wore on that fateful day. Though Ripstein had a major career that continues to this day, he doesn't rate an entry in any of the three film encyclopedias I own. He's been influential, though: Alex Cox has said, "In the 1990s all the feature films I made were shot in a style the Mexicans call 'plano secuencia' (a single master for every scene). I was inspired in this by my friend the director Arturo Ripstein." I like the way he moves his camera, often gliding elegantly around his people rather than deploying conventional shot/countershot. I enjoyed the occasional strange cut, wherein he'll switch location in mid-conversation. The sound design, too, is sometimes distorted and subjective, as when the ticking of a clock seems to quicken and get louder, as if it were a nervous woman's heartbeat. Note the visual elaboration of certain thematic elements (fathers and sons, fate), such as the moment when the older son catches a glimpse of himself in a mirror on a high wall, and in the frame he looks just like the painting of his late father he keeps in his room. Alex Phillips's sensory cinematography makes us feel the dusty heat coming off the cobblestones, and the guitar-based score by Carlos Jiménez Mabarak is lovely and plaintive. All the heavy thematic material, straight out of Greek tragedy as it is, could sound ponderous, but it never really is (even if it is a bit self-conscious at times). Instead, it's a movingly primal and classical tale. García Márquez once acknowledged the thread in his work of "love that encounters obstacles." "Love and death are always very close," he went on. "That's something Shakespeare invented before us." All of this is very much on the screen in TIME TO DIE. (1965, 88 min, DCP Digital) SP

Don Hertzfeldt’s IT’S SUCH A BEAUTIFUL DAY (Contemporary Animation)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Tuesday, 6pm

Rising to prominence during the early age of internet videos thanks to REJECTED (a series of animated commercials that were rejected due to their creator’s slipping sanity), cult animator Don Hertzfeldt spent ten years to complete this masterwork. Originally created as three separate shorts (EVERYTHING WILL BE OK, I AM SO PROUD OF YOU, IT’S SUCH A BEAUTIFUL DAY), the film combines the aforementioned titles into one succinct feature. Most notable about the film is Hertzfeldt’s distinct animation style, which combines somewhat simplistic stick figures with visual effects and real life footage. The film centers on Bill, an everyman whose only distinguishing feature is the Buster Keaton-esque hat on his head. An unseen narrator describes Bill’s actions and what transpires in his mind. Don’t let the simple animation fool you; the film’s story is rich and contemplative. Hertzfeldt raises deep questions: What makes a life?, Is time nothing but a concept rather than something tangible?, and Does any of this [life] really matter? The film also delves into illness and psychosis. These topics are best exemplified by the film’s frantic editing and rattling effects, wherein Bill is subjected to an onslaught of everyday occurrences that threaten an existential washing away of who he is. Calling to mind some of David Lynch’s more surreal works and also his animated short series DUMBLAND, IT’S SUCH A PERFECT DAY is profound and darkly funny, a movie that reminds one to take stock of the little things in life. Preceded by Hertzfeldt’s 2015 short WORLD OF TOMORROW (17 min, DCP Digital). Film scholar Donald Crafton lectures. (2012, 62 min, ProRes File) K

Antonio Pietrangeli’s I KNEW HER WELL (Italian Revival)

Doc Films (University of Chicago) – Monday, 7pm

Like an Italian counterpart to Robert Mulligan’s INSIDE DAISY CLOVER (released the same year), I KNEW HER WELL dismantles popular notions of celebrity and show business, rendering both nightmarish and sad. The film centers on Adriana, a fashion model rising through the ranks of Italy’s culture industry, charting her development through her relationships with men. The clever structure makes I KNEW HER WELL feel a bit like a series of short films, as the episodes are separated by extended periods of time. (Also, the men rarely reappear from one episode to the next.) Adriana appears at the start of each episode like a new woman, as she alters her appearance based on current trends as well as whatever social class she’s navigating at the time. Stefania Sandrelli gives an incredible performance—you really don’t recognize her from time to time, so thoroughly does she transform herself from scene to scene. Of course, there’s a dark side to her transformations, which speak to the character’s shallowness; perhaps she has no true self, which is why it’s so easy for her to transform. Adriana’s downfall turns out to be her sense of trust, which is, ironically, also her greatest virtue. She tries to see the best in each man she gives herself to, but in doing so, she blinds herself to what is callous, cruel, or downright exploitative in men. The great Ettore Scola collaborated on the script, which is full of Godardian insights into the ways that cultural experience affect personal identity. Antonio Pietrangeli’s direction is a little modish, indulging in flashy stylistic flourishes clearly inspired by the Nouvelle Vague; in hindsight, though, the stylization makes sense, as it reflects Adriana’s enthrallment to the zeitgeist. (1965, 115 min, DCP Digital) BS

Andrea Arnold's FISH TANK (New International)

Doc Films (University of Chicago) – Thursday, 7pm

The sophomore feature from Andrea Arnold is a raw and unsettling portrait of 15 year-old Mia, a girl living in a dismal UK housing project with her dysfunctional mom and little sister. Katie Jarvis delivers a robust portrayal as her character confronts her developing sexuality and personal independence. Much like her first film, the BAFTA-sweeping RED ROAD (2006), Arnold doesn't pull any punches when it comes to the flaws of her female characters. Mia's teenage experience is disconcerting and made even dangerous at times by her surroundings. She is foul-mouthed and cagey, but to Arnold's credit we don't hesitate to identify with her. The scope of the movie is completely Mia's experience; the camera moves with her in almost every shot. When her mother gets an attractive new boyfriend, played by Michael Fassbender, things start to spiral downward fast. FISH TANK fits well in the British tradition of social realism movies, but banishes any sentimentality in exchange for allowing its characters to respond fully to their ever-worsening circumstances. Still, in all that goes wrong, Arnold provides Mia, and thereby the audience, small moments of rest, beauty, and limited transcendence. (2009, 122 min, 35mm) C

Steven Spielberg's JAWS (American Revival)

Music Box Theatre – Wednesday, 7pm

If PSYCHO forever changed bathroom behavior, then JAWS no doubt gave us pause before diving head first into the ocean; but like the best horror movies, the film's staying power comes not from it's superficial subject matter, in this case a mammoth, man-eating shark and the ominous abyss of the deep blue sea, but from the polysemic potential and wealth of latent meanings that these enduring symbols possess. JAWS marks a watershed moment in cinema culture for a variety of reasons, not excluding the way it singlehandedly altered the Hollywood business model by becoming the then highest grossing film of all time. A byproduct of such attention has been the sustained output of scholarly criticism over the years. At the time of its release, JAWS was interpreted as a thinly veiled metaphor for the Watergate scandal (an event that was slightly more conspicuous in the book), but since then a variety of readings have emerged, including socioeconomic and feminist analyses; however, Marxist theorist Fredric Jameson may provide the most intriguing interpretation by connecting the shark to the tradition of scapegoating. Like Moby Dick or Hitchcock's titular birds, the shark functions a sacrificial animal onto which we project our own social or historical anxieties (e.g., bioterrorism, AIDS, Mitt Romney). It allows us to rationalize evil and then fool ourselves into thinking we've vanquished it. But by turning man-made problems into natural ones we forget that human nature itself is corrupt, exemplified here by Mayor Vaughn who places the entire population of Amity Island in peril by denying the existence of the shark. Jameson's reading is in keeping with the way in which Spielberg rarely displays the shark itself (the result of constant mechanical malfunctions); as opposed to terrifying close-ups, we get point of view shots that create an abstract feeling of fear, thus evoking an applicable horror film trope: the idea is much more frightening than the image. JAWS is a timeless cautionary tale because it appeals to the deep-rooted fears of any generation. And because sharks are scary. Kevin Feldheim, Manager of the Pritzker Laboratory for Molecular Systematics and Evolution, will give a talk after the film. (1975, 124 min, 35mm) H

Marlon Brando's ONE-EYED JACKS (American Revival)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Saturday, 3pm and Monday, 6:30pm

We should be happy Stanley Kubrick didn't get to direct ONE-EYED JACKS. Not that the work he would've produced wouldn't have been good, but we wouldn't have the singular film we have now. Kubrick had a tangle with Marlon Brando over the direction of the film, which would've been his only Western, and was promptly replaced by the star himself, who shot this, his only directorial work, as a sort of anti-Kubrick film—a movie that is precisely imprecise. Brando's cut ran five hours; the clarity of the version Paramount released only seems to reinforce the murk of the original. In no American Western do the genre's symbols seem so shallow; the Pacific ocean-side setting gives the film a sense of the terminal—it's a story at the end of the line. The sound (nowhere have spurs and guns jangled so much) only reinforces the doomed hollowness. It's a bleak film, possibly because, as an actor, Brando's sympathy lay with people and not with images. (1961, 141 min, DCP Digital) IV

Frederick Wiseman's TITICUT FOLLIES (Documentary Revival)

Music Box Theatre – Sunday, 2:15pm

Acclaimed documentarian Frederick Wiseman's career focus has been the documentation and analysis of institutions, be it high school, the hospital, Army training, or most recently, the Idaho state legislature (STATE LEGISLATURE plays at Chicago Filmmakers in March). TITICUT FOLLIES, his first film, exposes the dire workings of a Massachusetts mental institution in the late 1960s. This unflattering portrayal landed the film in a legal struggle for general distribution, blocked as it was by the State of Massachusetts, which was finally resolved in 1991. Though the film unfortunately missed out on the political punch it could have had were it widely released in 1967, it still manages to shock and appall audiences with the graphic mistreatment of the inmates. What could and should have been a whistle-blowing film is now merely a document of past abuses. It is still compelling nonetheless. Even though it is mostly remembered as a harrowing exposé, it isn't all doom and gloom. The title of the film shares its name with the play the inmates put on for their guards and nurses. It is a swirling, bizarre pageant that casts light, however dim, on the inmates' lives. This is Wiseman's signature move as a documentarian: to show that institutions, even flawed and failing ones, are a complicated web of good and bad with no easy solutions. (1967, 84 min, DCP Digital) D

---

This “Art House Theater Day” screening includes never before seen trial footage plus a special pre-recorded conversation between Frederick Wiseman and Wes Anderson.

John Ford's UPSTREAM (Silent American Revival)

Northbrook Public Library (1201 Cedar Lane, Northbrook) – Wednesday, 1 and 7:30pm (Free Admission)

Though the vast majority of silent films are gone forever—lost, destroyed, or decayed beyond salvage—miraculous discoveries still occur from time to time. For instance in 2009, when an exciting lot of silent American films was uncovered in a New Zealand archive, returning to historians and viewers a sampling of short westerns, comedies, animated films, and melodramas—including UPSTREAM, a silent comedy by John Ford. Made in 1927, this backstage story finds Ford well past his early period of quickly-produced westerns and foreshadows some of the more diverse and ambitious projects to come. As he closed out the silent years and moved into his wildly eclectic run in the 1930s, Ford would experiment with many styles and genres before more-or-less returning to westerns as a primary focus with STAGECOACH in 1939. An unusual title for Ford, UPSTREAM is on the cusp of this transition. Dave Kehr says that UPSTREAM exhibits influences from F.W. Murnau and German Expressionism (thus it can be seen as a mild stylistic precursor to his 1935 film THE INFORMER) and Richard Brody writes that, "far from being a mere historical curiosity, the movie is a delight and a wonder—it's a thoroughgoing John Ford film, one that's artistically worthy to take its place among his many classics." Brody’s assessment is overly generous; the film is perhaps mid-level Ford at best (though not without some undeniable merits). What it definitely is, though, is a fascinating glimpse at a key transitional period for Ford, and one we’re lucky to have, given that only about 15% of Ford's silent films survive. Preceded by Charles Chaplin’s 1916 short film THE FIREMAN (24 min, Unconfirmed Format). Live accompaniment by David Drazin. (1927, 60 min, DCP Digital) PF

Andrei Tarkovsky's STALKER (Soviet Revival)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Saturday, 7:30pm, Sunday, 2:15pm, and Thursday, 6:30pm

Loosely based on the Soviet novel Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Tarkovsky's STALKER creates a decrepit industrial world where a mysterious Zone is sealed off by the government. The Zone, rumored to be of alien origin, is navigable by guides known as Stalkers. The Stalker of the title leads a writer and a scientist through the surrounding detritus into the oneiric Zone—an allegorical stand-in for nothing less than life itself—on a spiritual quest for a room that grants one's deepest subconscious wish. Tarkovsky composes his scenes to obscure the surroundings and tightly controls the audience's view through long, choreographed takes. Shots run long and are cut seamlessly. Coupled with non-localized sounds and a methodical synth score, sequences in the film beckon the audience into its illusion of continuous action while heightening the sense of time passing. The use of nondiegetic sounds subtly reminds us that this may be a subjective world established for the Stalker's mystical purpose. Where sci-fi films tend to overstate humanity's limitless imagination of the universe, Tarkovsky reappropriates the genre's trappings to suggest the cosmos' deepest truths are in one's own mind. STALKER posits—perhaps frighteningly—that, in this exploration of the self, there is something that knows more about us than we know ourselves. The writer and scientist, both at their spiritual and intellectual nadir, hope the room will renew their métier; the Stalker's purpose, as stated by Tarkovsky, is to "impose on them the idea of hope." But STALKER is a rich and continually inspiring work not for this (or any other) fixed meaning but rather for its resistance to any one single interpretation. (1979, 163 min, DCP Digital) B

Kogonada's COLUMBUS (New American)

Music Box Theatre – Check Venue website for showtimes

I cherish Kogonada's COLUMBUS for what it values, and questions, in architecture and cinema both. At the same time, it's a thoughtful, moving story of a budding friendship that becomes a form of love, and a middle-aged man contemplating a parent's mortality. Kogonada is a justly celebrated video essayist; I highly recommend you visit his site, kogonada.com, and check out his beautiful, exhilarating video essays on the likes of Ozu, Godard, Bresson, Bergman, Malick, Kubrick, Hitchcock, Tarkovsky, and Kore-eda. He wrote, directed and edited this dramatic feature debut, and he's filled it with compositional homages: Kubrick's one-point perspective, Ozu's passageways, Bergman's mirrors. It's about a pensive, melancholy middle-aged man (John Cho) who arrives in Columbus, Indiana, from Seoul, after his estranged father, a noted professor of architecture, falls into a coma. Columbus is a small, rural midwestern town that also happens to be a kind of open-air museum, where some of the greatest figures in Mid-Century Modern architecture created masterpieces of the form. (Just for starters, there's First Christian Church by Eliel Saarinen, North Christian Church by his son Eero, and Michael Van Valkenburgh's beautiful Mill Race Park, with its covered bridge and lookout tower.) While waiting on the fate of his father, Cho forms a friendship with a bright, young working-class woman (Haley Lu Richardson), an "architecture nerd" who's stayed in town a year after high school because she's essentially a mother for her own mother, a recovered meth addict (Michelle Forbes). He also gets reacquainted with his father's protégé (Parker Posey), who's just a couple years older than he. We only see his father, truly, at the beginning: from a distance, standing with his back to us in the gardens of Eero Saarinen's famous Miller House. (Watch for, and think about, how this sequence is mirrored later in the film.) Yet his father's absence is seen and felt throughout, as Cho moves through the man's vacated rooms at the historic Inn at Irwin Gardens: in a game of Chinese checkers with the absent man, in his hat on a chair. (Kogonada frequently deploys still-life views, absent of the people who were present before, or will be later.) The movie features beautifully-played interaction by the actors, as they circle and discover one another and make, or miss, connections. (As in Bresson, Kogonada's characters express feelings beyond words with hands: a squeeze, a caress.) Previously known for comedy, Cho gives a fine dramatic performance. Richardson is amused by other people, and I enjoyed watching that amusement break over her face, as well as the wonder when she engages the buildings, tracing their contours with her hand. She's also good at showing the wrenching burden for a young person of carrying the world on her shoulders. At the local library, designed by I.M. Pei, she shelves books alongside her co-worker, a thoughtful grad student who's not quite her boyfriend (Rory Culkin, who tickled me, as he does her, with the earnest way he engages ideas.) At the Republic newspaper offices, a historic building designed by Myron Goldsmith, Richardson applies for a newsroom job; this also happens to be where her mother cleans at night. This gets to the crux of Kogonada's concerns. What is the effect of these buildings, if any, on contemporary everyday life? What is the legacy for modern human beings of the modernists' promise that architecture could change the world? That, as Polshek believed, architecture is the healing art, the one that has the power to restore? If the buildings are just the unnoticed, almost unseen, places where people live and work, whose failure is it, if anyone's? As shot by Elisha Christian, Columbus is a magical place, but there's something forlorn about it, as well, as if the buildings are telling their own story about the way their spirit has been abandoned. For her part, Richardson likes to park her car in the middle of the night and sit in front of Deborah Berke's Irwin Union Bank, glowing ghostly in the darkness. She tells Cho the story of how she'd probably seen it a thousand times, until the day, near her darkest hour, when she finally saw it. Suddenly, the place she'd lived her whole life felt different. There is a vision here, of art as comfort, and maybe even life-saver, that at least begins to answer some of the questions the film’s asking. (2017, 104 min, DCP Digital) SP

MORE SCREENINGS AND EVENTS

The new screening series Cinema 53 presents The Combahee River Collective Mixtape: Black Feminist Sonic Diss at the Harper Theater (5238 S. Harper Ave.) on Thursday at 7pm. This multimedia presentation by scholars Daphne A. Brooks (Yale), Kara Keeling (USC) and Jacqueline Stewart (Univ. of Chicago) takes as a starting point the 1977 “Combahee River Collective Statement,” which was a “radical articulation of the tenets and goals of a truly revolutionary Black feminist theory and praxis.” Free admission.

The Chicago Film Society (at Northeastern Illinois University, The Auditorium, Building E, 3701 W. Bryn Mawr Ave.) screens Mitchell Leisen’s 1946 film TO EACH HIS OWN (122 min, 35mm) on Wednesday at 7:30pm. Preceded by Dave Fleischer’s 1937 Popeye cartoon I LIKE BABIES AND INFINKS (7 min, 16mm).

Filmfront (1740 W. 18th St.) presents Sky Hopinka: On Loneliness - Post Colonial Vagaries (approx. 60 min, Digital Projection) on Sunday at 8pm. Hopinka will screen a selection of his own videos along with some works that have influenced him. Screening are Hopinka’s WAWA (2014) and ANTI-OBJECTS, OR SPACE WITHOUT PATH OR BOUNDARY (2017), along with Lindsay McIntyre’s THOUGHT SHE NEVER SPOKE, THIS IS WHERE HER VOICE WOULD HAVE BEEN (2008) and WHERE SHE STOOD IN THE FIRST PLACE (2010), Basma Alsharif’s WE BEGAN BY MEASURING DISTANCE (2009), and Caroline Monnet’s MOBILIZE (2015).

The Nightingale (1084 N. Milwaukee Ave.) screens Adam and Zack Khalil’s 2016 experimental documentary INAATE/SE/ [it shines a certain way. to a certain place/it flies. falls./] (75 min, Digital Projection) on Friday at 8pm, with the Khalils in person.

Asian Pop-Up Cinema presents Derek Hui’s 2017 Chinese film THIS IS NOT WHAT I EXPECTED (106 min, Digital Projection) on Wednesday at 7pm at AMC River East (322 E. Illinois St.); and presents a week-long run of Shinobu Yaguchi 2017 Japanese film SURVIVAL FAMILY (117 min, Digital Projection) at the Wilmette Theatre (1122 Central Ave., Wilmette). www.asianpopupcinema.org

The Davis Theater (4614 N. Lincoln Ave.) screens Rupert Julian’s 1925 silent film THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (approx. 93 min, Unconfirmed Format) on Friday at 8pm, with live organ accompaniment by Jay Warren. Preceded by Edward F. Cline and Buster Keaton’s 1921 silent short THE HAUNTED HOUSE (21 min).

The Chicago Media Project hosts a screening of David Byars’ 2017 documentary NO MAN'S LAND (81 min, Digital Projection) on Wednesday at 7pm, with Byars in person. The screening is free; the screening and a pre-film dinner is $35 (tickets at Eventbrite).

Black Cinema House at the Stony Island Arts Bank (6760 S. Stony Island Ave.) screens Leslie Harris’ 1992 film JUST ANOTHER GIRL ON THE I.R.T. (93 min, Digital Projection) on Friday at 7pm. Free admission.

Also at the Northbrook Public Library (1201 Cedar Lane, Northbrook) this week: Ethan Hawke’s 2014 documentary SEYMOUR: AN INTRODUCTION (84 min, Video Projection) is on Sunday at 3pm. Free admission. www.northbrook.info/events/film

Also at the Gene Siskel Film Center this week: Peter Bratt’s 2017 documentary DOLORES (98 min, DCP Digital) plays for a week.

Also at Doc Films (University of Chicago) this week: Jerry Schatzberg’s 1971 film THE PANIC IN NEEDLE PARK (110 min, DCP Digital) is on Wednesday at 7 and 9pm; and Chan-wook Park’s 2003 South Korean film OLDBOY (120 min, 35mm) is on Thursday at 9:30pm.

Also at the Music Box Theatre this week: Michael Roberts’ 2017 documentary MANOLO: THE BOY WHO MADE SHOES FOR LIZARDS (89 min, DCP Digital) opens; Martin Provost’s 2017 French film THE MIDWIFE (117 min, DCP Digital) continues; Frank Capra's 1939 film MR. SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON (129 min, 35mm) is on Saturday and Sunday at 11:30am; Kenji Kamiyama’s 2017 Japanese animated film NAPPING PRINCESS (110 min, Digital Projection) is on Saturday at 11:30am (English dubbed) and Monday at 7pm (Japanese with subtitles); Tommy Wiseau’s 2003 film THE ROOM (99 min, 35mm) is on Friday at Midnight; Jim Sharman’s 1975 film THE ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW (100 min, 35mm) is on Saturday at Midnight; and the Chicago South Asian Film Festival and the Music Box co-present an advance screening of Jennifer Reeder’s 2017 film SIGNATURE MOVE (80 min, DCP Digital) on Thursday at 7pm, with many cast and crew in person.

At Facets Cinémathèque this week: Camilla Hall’s 2017 documentary COPWATCH (99 min, Video Projection), Jason Zeldes’ 2015 documentary ROMEO IS BLEEDING (93 min, Video Projection), and Ingrid Jungermann’s 2016 film WOMEN WHO KILL (93 min, Video Projection) all play for week-long runs; and a “Teach-In” screening of Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 film DR STRANGELOVE OR, HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB (95 min, Video Projection) is on Monday at 6:30pm, followed by a discussion led by Rachel Bronson, Executive Director of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. Free admission for DR. STRANGELOVE (though donations are accepted).

At the Chicago Cultural Center this week: the 2017 WTTW-produced documentary MY NEIGHBORHOOD: PILSEN (approx. 60 min, Video Projection) is on Saturday at 2pm, followed by a discussion; and Cinema/Chicago presents a screening of Mariano Cohn and Gastón Duprat’s 2016 Argentinean film ALL ABOUT ASADO (90 min, Video Projection) on Wednesday at 6:30pm. Free admission.

At Comfort Film at Comfort Station Logan Square (2579 N. Milwaukee Ave.) this week: Video! Video! Video Festival Day 2 is on Friday at 7pm; and Robert McGinley’s 1990 film SHREDDER ORPHEUS (90 min, VHS Projection) is on Wednesday at 8pm, in the “Released and Abandoned: Forgotten Oddities of the Home Video Era” series. Free admission.

Sinema Obscura at Township (2200 N. California Ave.) presents TV Party 9 "A Celebration of Women in Film" on Monday at 7pm. Includes short films and trailers from Ava Threlkel, Gretchen Hasse, Dylan Mars Greenberg, Anya Solotaire, Tierza Scaccia, Marie Ultreya, Monika Estrella Negra, Katie Johnston-Saurus Dean, Allison A. Ramirez, Erin Coen, and Michelle Garza. Free admission. And on Thursday at 7pm, Sinema Obscura will be hosting a screening at Que4 Radio (no address listed; contact them for location), which will include work by Zach Rudd, Rob Steinberg, Mykee Anthony Morettini, Marc Wilkinson, Rev. David Holcombe, Dustin Puehler, Marie Ultreya, Lew Ojeda, Andrew Smith, Gretchen Hasse, and Nick Alonzo.

The Goethe-Institut Chicago (150 N. Michigan Ave., Suite 200) screens Philip Halver’s 2017 documentary BE-TROIT – THE PROJECT, THE IDEA (Unconfirmed Running Time, Video Projection) on Tuesday at 6pm. Followed by a discussion. Free admission.

The Alliance Française (54 W. Chicago Ave.) screens Claire Simon’s 2015 French documentary THE WOODS DREAMS ARE MADE OF (144 min, Video Projection) on Tuesday at 6:30pm. Introduced by Michael Naas, Chair of the Philosophy Department at DePaul University.

ONGOING FILM/VIDEO INSTALLATIONS

The SAIC Sullivan Galleries (33 S. State St., 7th Floor) presents Apichatpong Weerasethakul: The Serenity of Madness through December 8. The exhibition opens on September 16, and there is an Opening Reception on Friday from 6-9pm. The show features many short films and video installations by the SAIC grad, along with a selection of photography, sketches, and archival materials.

The Graham Foundation presents David Hartt’s installation in the forest through January 6 at the Madlener House (4 W. Burton Place). The show features photography, sculpture, and a newly commissioned film.

At the Art Institute of Chicago, British artist and filmmaker Steve McQueen’s video installation work END CREDITS (2012-ongoing), which is currently comprised on nearly 13-hours of footage and 19-hours of soundtrack, is on view until October 1.

The Art Institute of Chicago (Modern Wing Galleries) has Dara Birnbaum’s 1979 two-channel video KISS THE GIRLS: MAKE THEM CRY (6 min) currently on view.

CINE-LIST: September 22 - September 28, 2017

MANAGING EDITOR // Patrick Friel

ASSOCIATE EDITORS // Ben Sachs, Kathleen Sachs, Kyle A. Westphal

CONTRIBUTORS // Kyle Cubr, Christy LeMaster, Doug McLaren, Scott Pfeiffer, Michael W. Phillips Jr., Harrison Sherrod, James Stroble, Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, Brian Welesko