SAVE THE DATE!

Come support our mission at a fundraising party being thrown by the Scrappers Film Group and Pentimenti Productions on Friday June 21 from 6 - 10pm at their shared space on 329 West 18th Street, Suite 607, Chicago, IL 60616.

$10 suggested donation at the door. RSVP or donate here.

CRUCIAL VIEWING

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s ONE OF OUR AIRCRAFT IS MISSING (British Revival)

Chicago Film Society (at Northeastern Illinois University, The Auditorium, Building E, 3701 W. Bryn Mawr Ave.) – Wednesday, 7:30pm

The fourth collaboration by the legendary directorial duo Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, ONE OF OUR AIRCRAFT MISSING is a World War II drama that thrust the team into forces to be reckoned with. Commissioned by the United Kingdom to boost the moral of those involved in the war effort, the film follows six servicemen who are forced to bail out of their bomber over Holland and elude the Nazis, with assistance from some of the Dutch they meet along the way. The film’s most striking feature is its realistic portrayal of both the war and those involved with it. Lacking any kind of score, Powell opts to use the diegetic soundscape of war itself, complete with explosions, gunfire, and aircraft propeller’s whirring. The film’s special effects are quite astonishing, as it incorporates both real footage of Royal Air Force pilots intercut with scale models succumbing to the explosive attacks. Unlike other war films of its era, the film lends a sense of humanity to all sides portrayed, latching onto the narrative notion that each character involved is but a snowflake involved in the greater avalanche that was World War II. Intended to be another propaganda piece for the British Ministry of Information, ONE OF OUR AIRCRAFT IS MISSING surpasses this goal, passing into the realm of enthralling film viewing. Preceded by Owen Crump's 1952 film THEY FLY THROUGH THE AIR (12 min, 35mm). (1942, 102 min, 35mm archival print) KC

Jill Magid’s THE PROPOSAL (New Documentary)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Check Venue website for showtimes

Intellectual property and the ethics of current copyright law form the background of a story that chronicles the powerful, irrational emotions of love and obsession. American artist Jill Magid is intrigued by the colorful forms and geometric, open spaces influenced by the Modernist movement that renowned Mexican architect Luis Barragán (1902-1988) created. She makes the pilgrimage to his home in Mexico City, now a museum and a UNESCO World Heritage site, where she makes the inference that she is his lover by expecting to sleep in his bed; instead, she is shown to the guest bedroom where, she is told, all of Barragán’s girlfriends slept. She even tries to mingle with his spirit during Day of the Dead celebrations. Magid, however, is not his only spiritual lover. Federica Zanco, wife of Swiss furniture magnate Rolf Fehlbaum, fell under Barragán’s spell when she visited the same home in 1993. The story goes that the couple learned that the architect’s professional archive had been sold to a gallerist in New York and that Fehlbaum bought it for Zanco as an engagement present. Zanco moved the archive to Switzerland, formed the Barragan Foundation, and has for the last 25 years made the materials all but inaccessible. Magid begins a three-year correspondence with Zanco that seems to reflect a genuine friendship, but her ulterior motive is to gain access to the archive and, eventually, to persuade Zanco to repatriate it to Mexico. Professional fundraisers will find the years-long wooing of a prospective donor very familiar, though Magid, no doubt a frequent fundraiser for her own art projects, employs a very unusual tactic that you will have to see to believe. Ultimately, the covetousness of both women and the iron hammer of copyright law that the rich and powerful use for their own purposes are largely subsumed in the gorgeous visuals that Magid has created to seduce us into the world of Barragán. She accomplishes the rare feat of helping us to share in her admiration and obsession through the power of her visual artistry. (2018, 86 min, DCP Digital) MF

Lydia Moyer’s THE FORCING (Experimental)

The Nightingale (1084 N. Milwaukee Ave.) — Saturday, 7pm

Lydia Moyer's THE FORCING is a collage-style document—not a documentary, mind you, but with enough elements of one to bring the mode to mind—that contains a great many themes both juxtaposed against and married to one another. Its construction is graceful; Moyer's skills as an editor are lithe, the structure informing a clever strategy of apposition between image and sound. One first begins to sense her intent—having been eased into it with visually stunning images of a tornado, various flowers, and time-lapse footage of a glacier melting—when sounds of a dispute are heard, accompanying footage of deer inside a house. Moyer then cuts to the dispute in question, between police and protesters, then again to the deer, establishing what will soon become an expectation—that for every action, be it soothing or chaotic, there will be an equal and opposite reaction, the adverse of the other. She utilizes this premise throughout the duration of the film, pairing a benign image (often of nature) with disturbing audio, or disturbing imagery with benign audio, though it doesn’t become stale. Rather, like the images and sounds themselves—a mélange of beauty and terror—the impact of this strategy strengthens as it endures. By and large, the disturbing media are ripped straight from the headlines, including security footage of murder victim Hannah Graham, a student at the University of Virginia, and footage of the 2017 Charlottesville, Virginia, protest that resulted in numerous injured and one dead. (Moyer is an associate professor at the University of Virginia, a likely reason for including both.) At infrequent intervals, the pattern becomes a little more rhythmic, such as when a song, Diane Cluck’s “Red August,” is paired with red and blue flashes, like police lights, piercing the screen in time with the music. The pattern comes undone near the end, when, per Moyer, “boundaries between climate change and the struggle for social justice dissolve, relying on the energy of sound to place them side-by-side on the cosmic continuum,” with nature no longer an arbiter of reprieve, but rather a source of the “anxiety and stated toil” that Henry David Thoreau believed nature could becalm. Somewhere in all this is commentary on “how much is experienced through screens,” less obvious but brought to mind when, in the credits, Moyer thanks “everyone who keeps their camera on”; many of the images are results of the trend toward compulsive documentation. Preceding the film is Latham Zearfoss’ WHITE BALANCE (2018, 9 min, Digital Projection), another work that uses beautiful images, largely of things that are white, to confront the viewer specifically with regard to race. Interviews with figures in white sheets whose voices have been altered detail microaggressions that plague modern-day race relations, and shots of various toilets flushing, revealed to belong to several artists, realize, perhaps most truthfully, the current state of things. Moyer and Zearfoss in person. (2018, 46 min, Digital Projection) KS

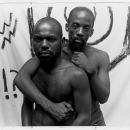

Marlon Riggs’ TONGUES UNTIED (Documentary/Essay Revival)

Stony Island Arts Bank (6760 S. Stony Island Ave.) – Sunday, 2pm (Free Admission)

One of the landmark works of queer film activism, Marlon Riggs’ TONGUES UNTIED is a treatise on the enforced silence of gay black men and an emphatic corrective to it. Through a sequence of poetry and monologues delivered by Riggs and fellow gay rights activists, the film centers and amplifies the subjectivities of this doubly oppressed group, giving space for their voices to not only be heard in all their multiplicity, but to directly address and challenge the dominant white, heteronormative patriarchy that deprives them of this privilege in the real world. Riggs conducts this address through an arsenal of techniques, including oral histories spoken directly to camera, musical interludes, instructional videos, and aural collage that often takes on the form of incantation. The last of these is introduced at the start of the film, as a rhythmic chant of “brother to brother” builds in volume and tempo over the soundtrack, becoming mantra. Riggs proceeds to weave voices over and through his images, catalyzing discourses around racism and homophobia and invoking cathartic personal stories of shame, abuse, anger, and self-hate. The voices are not all from positive figures; demonstrating the persecution he faced while growing up in Georgia, Riggs cuts to extreme close-ups of mouths spitting epithets, making a grotesque symphony out of words he would eventually internalize. In a similar, later scene, preachers shout sweaty, fire-and-brimstone rhetoric around the placid visage of poet and activist Essex Hemphill, whose silence, he and Riggs tell us, serves as both a shield from such pernicious intolerance and a cloak that locks them into invisibility and muteness. TONGUES UNTIED searingly relays how this muteness festers into rage. “Anger unvented becomes pain unspoken becomes rage released becomes violence cha cha cha,” another chant on the soundtrack goes, turning a maxim into a song. “It is easier to be furious than to be yearning, easier to crucify myself than you,” Hemphill admits. From these nakedly first-person accounts and their attendant, often confrontational images, Riggs makes perceptible the stifling feelings that, in a horrible irony, are instilled by the very culture that refuses their outlet. But in TONGUES UNTIED, they are spoken. Anger becomes mobilized into art and activism. The silence of the AIDS crisis is breached. In the early 90s, the impact of the film was such that the announcement of its broadcast on American public television caused an outcry, most notably from Pat Buchanan, who chastised Bush’s government for allowing such “pornographic and blasphemous art” to receive federal funding. Of course, nothing about the film is inflammatory. Its candor, its poetry, its sensuality, and its politics only solicit our empathy and action. Riggs passed from AIDS complications in 1994, but thirty years on from the release of this seminal film, his voice has never left us. (1989, 55 min, Video Projection) JL

Paul Verhoeven's TOTAL RECALL (American Revival)

Cinepocalypse at the Music Box Theatre – Saturday, 6:45pm

What if memory is not an individual repository of information and facts but instead a socio-technical product which may have already been commoditized? What if "being yourself" is a thoroughly unnatural and processual task of auto-impersonation (a fact which proper names do much to conveniently disguise)? And what if advanced technologies of perpetual surveillance and statist suppression are necessary to maintain the existing, illusory qualities of these concepts? The true artist knows all this already, and Paul Verhoeven is one such artist. With the felicitous help of Jost Vacano's characteristically lurid cinematography; Jerry Goldsmith's suggestive soundtrack, which slips oneiric themes between bombastic brass horns and soaring synths; the outrageous make-up effects of Rob Bottin's team; and ingenious location managers (casting Mexico's Distrito Federal as an estranged and already-austere future-city), Verhoeven here links underappreciated and everyday moral and philosophical dilemmas of identity and knowledge into a traditional and implausible hero narrative about a laborer (Arnold Schwarzenegger) leading a subaltern people's revolt against an autocratic mineral sheik (Ronny Cox). Actor Michael Ironside in person. (1990, 113 min, 70mm) MC

---

Showing as part of Cinepocalypse; see More Screenings below for additional information on the week-long event.

ALSO RECOMMENDED

David Mamet's THE SPANISH PRISONER (American Revival)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Saturday, 3pm and Tuesday, 6pm

David Mamet's Mannerist, deliberately stiff light thriller (or is it an homage to light thrillers?) where there are seemingly no characters, only people-shaped cogs in a neat little contraption that manufactures plot twists. The presence of poker-faced stage magician Ricky Jay in the cast gives away Mamet's game—to perform a series of writing-directing tricks for the audience—early on, but this—combined with the movie's controlled airlessness—is itself just a part of Mamet's complicated directorial ruse, which fascinatingly mirrors the one in the film. Campbell Scott plays a man being conned into believing he's being conned; he serves as the straightman to a cast—which includes Steve Martin, Ben Gazzara, Rebecca Pidgeon, Ed O'Neil, and Felicity Huffman—which delivers every line of dialogue with the flavor of impeccable stage patter. Altogether peculiar, perverse entertainment. (1998, 110 min, 35mm) IV

Claire Denis’s HIGH LIFE (New International)

Gene Siskel Film Center — Check Venue website for showtimes

“Beauty pisses me off,“ Claire Denis once said. No wonder Monte, the protagonist of HIGH LIFE, was first inspired by the greasily gaunt Vincent Gallo, Denis’s one-time muse of American scumminess, and subsequently developed for Philip Seymour Hoffman, whose mass of gut, skin, and stubble always felt tailored to fit a personal core of self-loathing. In the intervening years as the project sought funding, Gallo would burn out in a manner clownishly characteristic of the lowlifes he had played, while Hoffman would check out tragically so. Fifteen years on, HIGH LIFE comes to us at last, but in a fashion unimaginable at its time of origin. Claire Denis has officially broken out. Someone I met at a recent screening of L’INTRUS drove this home upon remarking the high volume of “youngs” in attendance. Robert Pattinson is one of these “youngs,” as are other members of the ensemble gathered around him here: Mia Goth, Ewan Mitchell, Claire Tran, and Gloria Obianyo—all in their twenties or early thirties. These millennials comprise one half of the crew that mans the spacecraft in HIGH LIFE. An older half consists of André Benjamin (yes, that André), Agata Buzek, Lars Eidinger—all early forties—and Juliette Binoche, the oldest at 55. I list the whole cast, leaving aside one key character, to emphasize how Denis has adapted her vision generationally to fit her leading man. The 32 year-old Pattinson has come to epitomize the current state of the film industry, where star actors pursue their personal favorite auteurs in an art house cinema version of millionaire spelunking. He has already drawn much deserved praise for the fierce commitment he brings to HIGH LIFE, but I’ve seen few considerations of how his presence, with all it implies, affects the ecological balance of Denis’s art and, more importantly, how she responds to it. This is not a matter of pop cultural status alone. It’s a matter of a certain type of beauty, the beauty Denis once reviled, as well as of youth. The director’s previous films are filled with both youth and beauty of course. Young, beautiful bodies, and the sense of temptation and taboo they invite, have animated Denis’s cinema from CHOCOLAT to 35 SHOTS OF RUM, but no actor Denis has previously engaged exudes the ethereal, almost sacred beauty of a Hollywood star like Pattinson, and Monte was not originally supposed to be young. Denis wanted Hoffman for Monte, because he seemed “tired of life.” The story she would tell around this tired man involved a failing spaceship light-years from earth, a morgue filled with dead bodies, and a newborn baby. Through flashback, it would emerge how the crew, death row convicts on a suicide run to a black hole, had self destructed under the mental and physical strain of their circumstances, leaving only this man caring for this baby, the spawn of kinky fertility experiments. HIGH LIFE preserves the outline, but embodied by Pattinson, Monte becomes less a figure of age and waste than of wasted potential and stunted growth. His youth and the youth of his fellow convicts suggest a surrogate family of orphans in juvenile detention, the older inmates Benjamin and Buzek—ship’s gardener and pilot respectively—surrogate older siblings, and Eidinger and Binoche—captain and doctor—their surrogate parents. For HIGH LIFE is a film about family, how a family forms between bodies in space, specifically when that space is a prison. Denis displays little interest in man’s relationship to technology or the possibility of the infinite, the major themes of nearly all space science-fiction since 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY. The spacecraft she conceives is a low-tech system of interconnected rooms organized along an inescapable corridor. The space beyond is an implacably black void promising nothing but descent. Here there is only the body, its needs and desires, and the space that maintains and preserves it, while also regulating, restraining, even satisfying it, without accommodation for pleasure. This focus on body matters has led many to draw a connection with Ridley Scott’s ALIEN and its related vision of space as a source of genetic hostility, but the comparison only functions on a conceptual level. The sensations of HIGH LIFE feel closer to Mario Bava’s ALIEN precursor PLANET OF THE VAMPIRES with its psychedelic eroticism, albeit channeled through the environmental existentialism of Andrei Tarkovsky’s SOLARIS. As in Bava, color filtered lights seem to encase the characters in an almost tangible manifestation of their repressed urges, and, as in Tarkovsky, the fecundity of earth, here represented in remnant form by the ship’s greenhouse, returns them briefly to the memory of home. At a more basic level, the signature physicality of Denis’ art achieves a greater concentration in this setting than her previous earth-bound projects ever permitted. The force of mere looks, gestures, and poses of the body in HIGH LIFE restores something of the formal balance between the abstract and the concrete that Howard Hawks perfected under the studio system in films like ONLY ANGELS HAVE WINGS and RIO BRAVO. And just as Hawks required the muscular presences of Cary Grant and John Wayne to hold the center of mythic constructions, Denis needs Pattinson in HIGH LIFE for his iconic potency. Again and again, Denis cuts to images of her star’s head, shaven, shapely, in terrifyingly intimate close ups. These shots register the repressive effect of each new trauma Monte witnesses, each new indignity he endures, over the course of this most perverse space odyssey. By the film's end, it seems we have spent a lifetime with this once young man, drawn by the decay of time, the weight of gravity, the predations of people, in this prison of space. (2018, 110 min, DCP Digital) EC

Olivier Assayas’ NON-FICTION (New French)

Music Box Theatre — Check Venue website for showtimes

Olivier Assayas’ witty, deceptively simple NON-FICTION begins with a comically tense scene in which Alain, (Guillaume Canet), a suave book publisher, and Leonard (Vincent Macaigne), a Luddite author whose controversial novels are thinly disguised autobiography, argue about the virtues of Twitter. The seemingly meandering narrative that follows belies a clever structure that resolves itself 90-odd minutes later with Shakespearean symmetry when both men vacation together with their wives: Alain’s partner, Selena (Juliette Binoche), is a television actress ambivalent about her recent success on a cop show, and Valerie (Nora Hamzawi), Leonard’s wife, is a high-profile attorney and the breadwinner in their relationship. This quartet represents a spectrum of diverse attitudes towards globalization and humanity's slavish dependence on technology in an increasingly digital world yet it is to Assayas’ credit as a writer that they also always come across as fully fleshed-out characters, never mere mouthpieces for differing points-of-view. It’s the talkiest film Assayas has yet made though the dense dialogue scenes are cleverly edited in a brisk, Fincher-esque manner, and he often generates humor through the surprising way he ends scenes abruptly. It’s a substantial new chapter in an important body of work, one that illustrates the director’s philosophy that the role of the artist is to invent new tools to comment on a modern world that’s always changing. (2018, 106 min, DCP Digital) MGS

Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman’s LOVING VINCENT (New Polish/British Animation)

Gene Siskel Film Center – Friday and Saturday, 2pm, and Tuesday, 6:30pm

A breakthrough work, Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman’s LOVING VINCENT is comprised of 65,000 gorgeous oil paintings, on canvas, executed by a team of over 125 classically trained painters, working from live-action reference footage and Van Gogh's own paintings. A pulsing, exhilarating experience, I imagine it will only continue to find new audiences: I'm one of them. What the filmmakers have managed to do is get Van Gogh's experience of life, of nature, on screen, in all its richness and lust. Connoisseurs will love the details: you can hear that horse famously in the center-background of Cafe Terrace at Night clip-clopping towards you, under the starry, starry night. It's a pretty staggering technical accomplishment—you can enjoy it just for the texture of those big, thick, swirling impasto brushstrokes. But what's really remarkable is how they were able to craft a story with an emotional impact that does justice to this life, and to a body of work in which so many continue to take solace. The story takes us from Arles in the south of France, via Montmartre, to Auvers-sur-Oise in the north, where Van Gogh died in 1891. It's a year later, and we join Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth), the son of Postman Joseph Roulin (Chris O'Dowd), on his quest to deliver the last letter written by lonely, ill Van Gogh (Robert Gulaczyk) to his brother Theo (Cezary Lukaszewicz). Each character is a famous Van Gogh portrait come to life. There's Dr. Gachet (Jerome Flynn); his daughter Marguerite (Saoirse Ronan), at her piano or in her garden; innkeeper Adeline Ravoux (Eleanor Tomlinson). Sometimes, as with the Boatman (Aidan Turner), they've imagined a character based on "just a really tiny character at the shore of the river in a painting," as Kobiela put it. Miraculously, these all ring true as real, dimensional humans. Playing detective, Armand questions them about what really happened on the days leading up to Van Gogh's death: suicide, murder, or accident? Color—throbbing, shimmering, clashing—is for the present; black and white, evoking the greys of Van Gogh's early Nuenen style, is for memories. To describe the film's structure, critics have evoked CITIZEN KANE or RASHOMON. The surreal visual experience they've compared to WAKING LIFE—there's a similar feeling of life as a waking dream, which reminded me of AKIRA KUROSAWA'S DREAMS, with our Marty Scorsese as Van Gogh. ("The sun! It compels me to paint!") I was even reminded of JFK, what with Dr. Mazery's musings on what we might call the "Rene Secretan theory." Everyone Armand talks to has a different theory about "why," a different perspective on who and what we saw before. I think what he comes to understand is that he's looking in the wrong place. The truth is in the beauty, and the life force, of what Van Gogh left behind, a love this film celebrates in every frame. Cracking entertainment, too. A modern classic. (2017, 94 min, DCP Digital) SP

---

Showing as a double feature with Miki Wecel's 2019 Polish documentary about the film, LOVING VINCENT: THE IMPOSSIBLE DREAM (60 min, DCP Digital).

MORE SCREENINGS AND EVENTS

Cinepocalypse, a week-long showcase of genre films, continues through Thursday at the Music Box Theatre. In addition to a full slate of new features and shorts and some special events, Cinepocalypse includes several retrospective screenings: Paul Verhoeven’s TOTAL RECALL (see Crucial Viewing above) and Joel Schumacher’s 1990 film FLATLINERS, both in 70mm; Peter Markle’s 1984 film HOT DOG…THE MOVIE (DCP Digital); the original R-rated “gore-cut” of Stewart Raffill’s 1994 film TAMMY AND THE T-REX (35mm archival print); and Michael Lehmann’s 1994 film AIRHEADS (35mm), with Lehmann in person. Check the Music Box website for the full schedule.

Chicago Filmmakers (5720 N. Ridge Ave.) and the Chicago Film Archives present Out of the Vault: The Somersaulter-Moats & Somersaulter Super Premiere Film Event (71 min total, 16mm) on Saturday at 7pm, with filmmakers JP Somersaulter, Lillian Somersaulter Moats, and Michael Moats in person. The program features nine works made between 1973 and 1989 alone and in various collaborative combinations.

Chicago Filmmakers (5720 N. Ridge Ave.) screens Stephan Lacant's 2013 German film FREE FALL (101 min, Digital Projection) on Friday at 7pm.

Also at The Nightingale (1084 N. Milwaukee Ave.) this week: Films by Laura Harrison and Benjamin Capps is on Friday at 7:30pm, with the filmmakers in person. The program includes three works by Capps (2014-18, 31 min total) and three by Harrison (2013-16, 31 min total). Digital projection.

Block Cinema (Northwestern University) presents NU Docs Program 3: Structures on Friday at 7pm (preceded by a reception at 6:15pm). This third of three programs of work by Northwestern MFA students includes Will Klein's CHILDREN OF THE MOON (17 min), Jiayu Yang's I DREAM OF VIETNAM (16 min), Ziyi Yang's NINETEEN NINETY-NINE (12 min), and Jessica Scott's THE COLOR OF SKIN (20 min). Free admission.

South Side Projections and the DuSable Museum (at the DuSable) screen Tom Davenport's 1986 documentary A SINGING STREAM: A BLACK FAMILY CHRONICLE (57 min, Digital Projection) on Saturday at 2pm.

The Illinois Holocaust Museum (9603 Woods Dr., Skokie) screens Rubi Gat's 2017 Israeli documentary DEAR FREDY (74 min, Video Projection) on Thursday at 6:30pm, followed by a discussion. Free with museum admission; RSVP required at www.ilholocaustmuseum.org.

Also at the Stony Island Arts Bank (6760 S. Stony Island Ave.) this week: episodes from the FX television series Pose screen on Friday at 6pm, followed by a discussion and then at 8pm, a vogue workshop. Free admission.

The Instituto Cervantes (31 W. Ohio St.) screens Jonás Trueba's 2015 Spanish film THREE FOR THE ROAD (70 min, DVD Projection) on Tuesday at 7pm. Free admission.

The Beverly Arts Center screens John Sayles' 1988 film EIGHT MEN OUT (119 min, Digital Projection) on Wednesday at 7:30pm.

Also at the Gene Siskel Film Center this week: Gabriel Abrantes and Daniel Schmidt's 2018 Portuguese/French film DIAMANTINO (97 min, DCP Digital) plays for a week; Robert Sedláček's 2018 Czech film JAN PALACH (124 min, DCP Digital) is on Friday at 8pm and Thursday at 7:45pm; Arwen Curry's 2018 documentary WORLDS OF URSULA K. LE GUIN (69 min, DCP Digital) is on Saturday at 5:15pm (followed by a panel discussion) and Wednesday at 6pm (followed by an audience discussion); Radim Špaček's 2018 Czech/Slovak film GOLDEN STING (106 min, DCP Digital) is on Sunday at 5:15pm and Monday at 7:45pm; and Daniel Alpert, Greg Jacobs, and Jon Siskel's 2018 documentary NO SMALL MATTER (74 min, DCP Digital) is on Thursday at 8:15pm, with the filmmakers in person (the film continues with a week-long run starting June 21).

Also at the Music Box Theatre this week: David Robert Mitchell’s 2018 film UNDER THE SILVER LAKE (139 min, DCP Digital) continues; and Frédéric Tcheng's 2019 documentary HALSTON (105 min, DCP Digital) is on Saturday and Sunday at 11:15am.

Facets Cinémathèque plays Isabelle Dupuis and Tim Geraghty's 2018 documentary THE UNICORN (92 min, Video Projection; filmmakers in person at the Friday and Saturday screenings) and Jay Stern's 2018 UK film SAY MY NAME (83 min, Video Projection) for week-long runs; and a free screening of Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne's 1999 French/Belgian film ROSETTA (95 min, Video Projection) on Sunday at 2pm, followed by a discussion. This event is presented in conjunction with the publication of Luc Dardenne's book of journals, On the Back of Our Images (1991–2005).

The Chicago Cultural Center screens Josh Howard's 2017 documentary THE LAVENDER SCARE (77 min, Video Projection) on Saturday at 2pm, followed by a discussion; and hosts the Cinema/Chicago screening of Cho Sung-kyu's 2018 South Korean film PASSING SUMMER (93 min, Video Projection) on Wednesday at 6:30pm. Free admission.

Comfort Film at Comfort Station Logan Square (2579 N. Milwaukee Ave.) presents an outdoor screening of Roland West's 1925 silent film THE MONSTER (86 min, Digital Projection) on Wednesday at 8:30pm, with live accompaniment by Echo Haus. Free admission.

The Millennium Park Summer Film Series (at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion) begins this Tuesday at 6:30pm with Greg Berlanti's 2018 film LOVE, SIMON (110 min). Free admission.

ONGOING FILM/VIDEO INSTALLATIONS

Michael Robinson’s 2015 video MAD LADDERS (10 min) is on view in the group show Shall we go, you and I while we can at the Carrie Secrist Gallery (835 W. Washington Blvd.) though June 15.

Local videomaker, artist, writer, activist, and educator Gregg Bordowitz is featured in a career retrospective exhibition, I Wanna Be Well, at the Art Institute of Chicago through July 14.

Also on view at the Art Institute of Chicago: Martine Syms' SHE MAD: LAUGHING GAS (2018, 7 min, four-channel digital video installation with sound, wall painting, laser-cut acrylic, artist’s clothes).

CINE-LIST: June 14 - June 20, 2019

MANAGING EDITOR // Patrick Friel

ASSOCIATE EDITORS // Ben Sachs, Kathleen Sachs, Kyle A. Westphal

CONTRIBUTORS // Michael Castelle, Edo Choi, Kyle Cubr, Marilyn Ferdinand, Jonathan Leithold-Patt, Scott Pfeiffer, Michael G. Smith, Ignatiy Vishnevetsky