📽️ CRUCIAL VIEWING

Jean Vigo's L'ATALANTE (France)

Film Studies Center (at the University of Chicago) – Friday, 7pm [Free Admission]

There are movies that put you to sleep, and then there are movies that remind you that you are asleep: Jean Vigo's cryptically peerless L'ATALANTE, only somewhat recognizable as narrative cinema, sometimes seems as close a document as any of the inspired dreamlife of a modernizing Europe. Deliberately given an uninteresting screenplay by his producer, the literally feverish (he would die of Tuberculosis later that year) 28-year-old Jean Vigo orchestrated (and improvised) the playful and violent titular floating world (partially filmed on an actual barge in the Seine) which would magically transport its honeymooning, rural protagonist Juliette (Dita Parlo) into the strange crowds and technological chaos of Parisian urbanity. And in his legendary performance of the barge's old hand Jules, Swiss actor Michel Simon portrays the rage and kindness of the perpetually besotted with an empathy worthy of WITHNAIL AND I's Richard E. Grant. Meticulously restored in 1989 from Vigo's notes, the resultant ludic limbo—where the provincial certainty and simplicity of heterosexual kinship is perpetually thrown into doubt—will be either recognizable as The Way We Live Now, or as an explicitly political affront to the dozing apathy of cultural conservatism in all of its forms. (1934, 89 min, 35mm) [Michael Castelle]

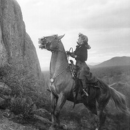

Anthony Mann's THE FURIES (US)

Music Box Theatre – Saturday and Sunday, 11:30am

If the western might be thought of as a simple genre, that of two-dimensional archetypes, breathtaking landscapes, and oversimplified racial and gender dynamics, then Anthony Mann could be said to have pushed the genre to its logical—and then often illogical—extreme, perhaps most blatantly in THE FURIES. Among the first of his many westerns, it’s an utterly outrageous film that’s anchored by the classic texts it references and the elegant beauty of Victor Milner’s cinematography, as informed by Mann’s visually minded direction. In Greek mythology, the Furies were goddesses of vengeance and retribution, referred to by one source as being “personified curses.” In Mann’s film, it’s the name of the sprawling estate helmed by T.C. Jeffords, a King Lear figure (Mann was obsessed with that particular Shakespeare play) played by Walter Huston, and his daughter, Vance, played by the indefatigable Barbara Stanwyck, who dominates the film as assuredly as Vance dominates the men in her life. THE FURIES opens with an exchange between Vance and her brother, who’s come home to get married and who appears again only once—this isn’t about Vance’s struggle with another man for her father’s affection, but, as the plot progresses, with another woman. The opening scene likewise finds Vance in her deceased mother’s bedroom, wearing her gown and jewelry, the unoccupied room a place of mysterious attraction for her father. If the Furies were curses personified, then this film is the Electra complex epitomized: the near-incestuous relationship between father and daughter is hardly subtle, with one recurring motif involving T.C. asking Vance to scratch his sixth lumbar vertebrae. Huston and Stanwyck are almost Shakespearean in their handling of this discomfiting behavior, so much so that the central, intentional romance between Vance and rogue businessman Rip Darrow, whose father was financially devastated by T.C., seems weak in comparison. (Not weak, however, is the romantic tension between Vance and Juan Herrera, a Mexican man whose family has been squatting on the Furies for decades. He loves her, and perhaps she him, though their bond is largely defined by her reluctance to kick his family off the land at her father’s request.) Things come to a head when T.C. goes on a trip and brings back Flo (the formidable Judith Anderson), who aims to take charge of both the man and the land. After Vance attacks Flo—with her mother’s scissors, natch—T.C. retaliates in such a way that spurs Vance to seek revenge. The method she undertakes is to buy up T.C.’s make-believe currency in order to acquire his estate. Based on a novel by Niven Busch (who penned the source material for THE POSTMAN ALWAYS RINGS TWICE and another Freudian western, King Vidor’s DUEL IN THE SUN), the complexities of its story are rendered visual by the astounding cinematography. “I believe in a visual conception of things,” Mann said in an interview with Claude and Charles Chabrol for Cahiers du cinéma. “The shock of glimpsing an entire life, an entire world, in a single little shot is much more important than the most brilliant dialogue.” Unlike the film version of DUEL IN THE SUN, the last several minutes of which is the strongest part, the ending of THE FURIES is the film’s weakest part, a fact pointed out by no less than critic Robin Wood. Given that its inspiration ranged from Greek mythology to Shakespeare to Dostoevsky’s The Idiot (Mann himself said that Busch based his novel off that canonical text), THE FURIES’ ambition may have been difficult to conclude. Despite this, it’s a veritable masterpiece—I’m hard pressed to think of a film so utterly singular yet so classically exquisite. Screening as part of the Working Girl: The Films of Barbara Stanwyck series. (1950, 109 min, 16mm archival print) [Kat Sachs]

Bette Gordon's VARIETY (US)

Doc Films (at the University of Chicago) – Monday, 7pm

There have been two great films about women working in porn theaters to enjoy revival within the past few years: Marie-Claude Treilhou's Paris-set SIMONE BARBÈS OR VIRTUE (1980) and Bette Gordon’s VARIETY (1983), the latter of whose protagonist takes tickets at one of New York City’s porn palaces of a grittier, pre-Giuliani yesteryear. Both are excellent, though the films have only superficial elements in common; where Treilhou's SIMONE BARBÈS is almost Varda-esque in its sexual and sociological whimsy, VARIETY is both more erotic and more alienating with regards to its protagonist’s concupiscent transformation. Sandy McLeod stars as Christine, an unemployed woman who learns of a job selling tickets at a porn theater, called Variety, from her bartender friend Nan (played by Nan Goldin). At first the job seems like an opportunity for bemusing anthropological study, an edgy but still suitable fortuity for Christine, whom it’s hinted at is a writer of some sort. But Variety soon yields an object of obsession for her: a mysterious, wealthy older man, a Michel Piccoli-type per Gordon’s own admission, who takes her to a baseball game only to leave midway through, after which Christine begins following him all around New York and even to Asbury Park, New Jersey. Her interest in the enigmatic businessman—who may or may not be a mafioso taking part in the fishmonger’s union scuffle that Christine’s journalist boyfriend (Will Patton) is investigating—is at once passive and acute, much like the gaze of the men looking at women on or behind the screens at Variety and other such voyeuristic establishments. Passive more so initially, as she quietly follows the man and begins making herself up more provocatively in the confines of her miniscule studio apartment; acutely in bewildering erotic monologues she delivers to her disinterested boyfriend and her increasingly erratic behavior toward this inexplicable object of her desire. Gordon, working from a script by Kathy Acker based on an original premise by the director, doesn’t just reverse the gaze but wholly assumes it, universalizing the elements of desire that compel us in our day-to-day lives and sometimes account for violent outbursts of yearning. It’s in this universalization—this wink to knowing audiences that women can and do have the same sexual impulses as men—that the protagonist is empowered and, by extension, those who identify as women in the audience, all of us satisfied in having reflected back to us our own prurient attraction and its mystifying impact. The cinematography by John Foster and future Jim Jarmusch collaborator Tom DiCillo emphasizes the sordid beauty of live-nude-girl sleaze, and music by John Lurie renders sonically what it means to look, to lurk, and to desire. Cinephiles are undoubtedly aware of how a movie theater can change you; it’s in her ticket booth, compressed between public and private spheres of desire, that Christine begins to realize her own. Screening as part of the City Serendipity series. (1983, 100 min, 35mm) [Kat Sachs]

Tsui Hark’s THE CHINESE FEAST (Hong Kong)

The Davis Theater – Sunday, 7pm

THE CHINESE FEAST is one of Tsui Hark’s live-action Looney Tunes, a gag-a-moment comedy that plays fast and loose with narrative logic and the laws of physics alike. It may reach its zenith during a set piece where Leslie Cheung must wrestle with a 200-pound fish all over a crowded restaurant. Cheung stars as a former Triad member trying to reinvent himself as a chef; too bad for him he’s inept in the kitchen and sets off elaborate accidents whenever he tries to cook. He gets a job at a restaurant whose owner is under pressure to sell out to a conglomerate called Super Group that wants to merge all the Chinese eateries in Hong Kong. The owner strikes a deal to take part in a cooking tournament against representatives of Super Group, with the wager being that his restaurant will keep its autonomy if he wins and will have to fold into the conglomerate if he loses. Somehow, the responsibility of competing in the tournament falls on Cheung, the owner’s wacky daughter, and a washed-up, alcoholic, one-time master chef who’s lost his sense of taste. There’s really no question of whether the underdogs will win—the film radiates so much feel-good energy that you can’t imagine anything disrupting the vibe—but it’s easy to get wrapped up in the suspense all the same. THE CHINESE FEAST may be Tsui’s most slapstick-driven movie, and the director brings the same invention and dynamism to physical comedy that he typically brings to action sequences; the film positively carries you along with its spirited momentum. There’s also a disarming childishness about THE CHINESE FEAST that adds to the fun, as Tsui and company deliver the lowbrow jokes with such gusto. Few filmmakers can get away with a fart joke as spectacularly. (1995, 103 min, DCP Digital) [Ben Sachs]

Off Center: Philip Mallory Jones (US/Experimental)

Siskel Film Center – Monday, 6pm

The development and release of consumer video technology was a breakthrough for independent documentary filmmaking. The late ‘60s and early ‘70s saw numerous artist-activists push the formal and political boundaries of the format, and organizations like Ithaca Video Projects emerged to organize the work being done on this new frontier. Philip Mallory Jones, one of the founders of IVP, is a prolific artist in his own right and has been continuing to explore the political possibilities of new technologies in filmmaking 50 years later. This week the Siskel Center’s Off Center series presents a small retrospective of his work curated by art historian Liz Kim that traces a clear line between his earlier video breakthroughs and his more recent digital-archival work. The first two films of the program come from a period in which Jones was collaborating often with his then-wife Gunilla. BEYOND THE MOUNTAINS MORE MOUNTAINS (1975), co-directed project by the two, documents a trip to Haiti and uses mixed modalities to create a portrait of the country that shows the affective power of a more poetic documentary style. The title comes from a Haitian proverb about the perpetual nature of struggle, but the Joneses are in a celebratory mode even despite the political text appearing in the film about the people’s hardships there. Jones’ digital interventions reduce groups of dancers to silhouettes, layering these over one another and on top of documentary footage and still images for a sort of visual bath of cultural production. NO CRYSTAL STAIR (1976) is in a similar mode, with Jones (solo this time) incorporating the dance of Blondell Cummings and poetry of Langston Hughes into a sort of freeform early-digital collage that both observes and contributes to an archive. The works in the program from the 1980s are more conventional but no less impressive, with the PBS-funded SOLDIERS OF A RECENT AND FORGOTTEN WAR (1981) presenting narratives of Vietnam War veterans in a more straightforward style, and WASSA (1989) playing more like a straight-up music video than the more complex collages of the ‘70s work. As Jones’ career went on, he would experiment with 3D modeling to create immersive environments and later as a sort of archival tool of physical space and its attendant culture and history. Several recent works have been connected to his now long-running project of creating a thorough 3D model of Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood in 1940. Originally planning to develop a video game from the material titled Dateline: Bronzeville, Jones ultimately had to scrap the idea and continued to use the 3D elements he had developed for 2D gallery works, and is refashioning the story he had written for the game into a novel and potentially a feature film. The largely AI-generated “concept sketch” for this film, the program’s last work DATELINE: BRONZEVILLE, A RUNNY WALKER MYSTERY (2025) is a bit hard to evaluate on its own due to being quite clearly not what a finished product would theoretically look like. One hopes that, at least, because the material we see here has the typical awkward and uncanny look of all gen-AI films, in a way that seems to undermine the diligent and detail-oriented work that Jones has put forth so far in this project. Even still, Jones’ 50+ year track record of thoughtful engagement with his materials leaves hope that he could find meaningful angles on even the most hideous of modern tools. (1975-2025, Total approx. 63 min, Digital Projection) [Maxwell Courtright]

Sarah Maldoror's SAMBIZANGA (Angola/France)

Siskel Film Center – Sunday, 1:15pm

The vexation of Kafka joined with the ferment of colonialism, Sarah Maldoror’s SAMBIZANGA—the first film produced by a Lusophone African nation, by some accounts the first feature to have been directed by a woman in sub-Saharan Africa, and the prolific Marxist filmmaker's second feature—is especially unnerving as it deals in the real-life terror of subjugation. Set in the titular village of Luanda (the capital city of Angola), the film follows the sudden arrest of Domingos, a manual laborer, on suspicion of being part of a covert resistance movement against the Portuguese colonialists; it also concerns his wife Maria as she tries to discover what’s happened to him, navigating a Trial-esque bureaucracy with their baby son fastened to her back. SAMBIZANGA was adapted from José Luandino Vieira’s 1961 novella The Real Life of Domingos Xavier by Maldoror, her partner Mário Pinto de Andrade (a founder of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola [MPLA], as well as its first president), and French novelist Maurice Pons. The story navigates between Domingos’ detention and Maria’s journey, with suggestions of the larger anti-colonialist liberation movement interwoven amidst them, showing how whisper networks of subversion facilitate the larger, eventual rebellion. Maldoror’s background is as varied as it is impressive. The daughter of a French mother and Guadeloupean father, born in southwestern France, she studied drama in Paris, where she was one of the founding members of Les Griots, a troupe of African and Afro-Caribbean actors. She later studied film in the Soviet Union under the tutelage of Mark Donskoy at the Moscow Film Academy, overlapping with Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène during his time there. In SAMBIZANGA, she adroitly communicates information in tandem with the narrative, resulting in something that edifies the curiosity of outsiders and immerses all spectators in the narrative trajectory. At the beginning of the film, a sheath of text augurs a real-life uprising that took place on February 4, 1961 in Luanda, when “a group of militants set out from Sambizanga… intending to storm the capital's prison. At the same time, they gave the signal for the armed struggle for national independence that has engulfed Angola ever since.” Domingos and Maria’s trials come to represent that which spurs the eventual uprising, which is fueled by the poverty and exploitation thrust upon them by the colonialist interlopers—a justifiable resentment patiently nurtured until the clandestine became justly impudent. Shot in the People’s Republic of the Congo, the film is not just a testament to the Angolan liberation movement of which the MPLA was a significant part but to the spirit of Pan-Africanism in general; Maldoror sees in various locales around the continent a common goal that transcends geography. That’s evident in the casting as well: primarily working with amateurs (with the exception of French actor Jacques Poitrenaud, who plays the white authority figure who tortures Domingos), Maldoror recruited Domingos Oliveira, an Angolan exile working in the Congo, to appear as the character of the same name, and Cape Verdean economist Elisa Andrade, who appeared in Maldoror’s 1968 short MONANGAMBÉ, plays Maria. Filmically it’s a stunning work, the expressive cinematography lending additional contours and its soundtrack another layer of emotional depth to the characters and thus the country’s harrowing struggle. Screening as part of the African Cinema from Independence to Now lecture series. (1972, 97 min, DCP Digital) [Kat Sachs]

📽️ ALSO RECOMMENDED

Jonathan Glazer's BIRTH (US/UK/Germany) and Gus Van Sant’s TO DIE FOR (US)

FACETS – Friday, 7pm (BIRTH) and 9pm (TO DIE FOR)

There are at least four auteurs of BIRTH (2004, 100 min, Unconfirmed Format)—co-screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, director Jonathan Glazer, cinematographer Harris Savides, and star Nicole Kidman—and what makes the film such an interesting (and, to some viewers, frustrating) experience is that it often feels as though they’re working at cross purposes. Carrière is the most widely lauded of the bunch, having begun his career as the co-writer of French comedian Pierre Étaix and gone on to collaborate with a range of great filmmakers that includes Milos Forman, Jean-Luc Godard, Andrzej Wajda, and Philippe Garrel. For all his accomplishments, though, he will always be best known for collaborating with Luis Buñuel on his final five features, and it’s Buñuel’s sensibility that looms largest over BIRTH; like many of the Spanish master’s films, it’s an elegant, deliberately nonsensical provocation. The premise of a wealthy woman falling madly in love with a 10-year-old boy who claims to be her long-deceased husband may well have tickled Buñuel, as he loved to show aristocrats behaving absurdly, though one wonders what the ever-modest filmmaker would have made of Glazer’s ornate approach, honed on music videos and indebted here to the mature work of Kubrick and Polanski. With its slow pacing, portentous line readings, and frequent Steadicam shots, BIRTH suggests a version of THE SHINING with all the overtly scary parts taken out. That may seem like a perverse strategy, but when you think about how perverse the subject matter is, it begins to make sense. The horror movie aesthetic is carried out brilliantly and given nuance by Savides, arguably the most exciting cinematographer of the 2000s with a résumé that includes James Gray’s THE YARDS (2000), David Fincher’s ZODIAC (2007), and multiple films by Gus Van Sant. The lighting and shadows often steal the show in BIRTH, and they augment the film’s theme of mourning. As Rocío Irizarry Nuñez wrote in the program notes of a Chicago Film Society screening, “Muslin was used for light diffusion, as though the film itself is swathed in a burial shroud.” And why shouldn’t it be? Kidman’s character has spent ten years in mourning when the story opens, and her dead husband is invoked so much that he leaves a greater impression than many of the onscreen players. The primary cast is stellar, though, from Lauren Bacall (as Kidman’s mother) to Danny Huston (as the perseverant dolt who wants to marry her) to Cameron Bright (as the creepy ten-year-old). Kidman deserves special mention for her high melodramatic performance, which seems almost magically unaware of how bizarre everything around her is. She gives herself totally to the role of a woman who, for the sake of love, will allow herself to believe in anything. In this way, Kidman comes across as the ideal movie spectator, just as would a few decades later in those ads they play before movies at AMC Theatres. [Ben Sachs]

---

The week TO DIE FOR (1995, 106 min, Unconfirmed Format) opened in 1995, a television cart rolled into my Social Studies class for the season finale of the O.J. Simpson trial. That timing, in retrospect, was prophetic. Where John Waters once scavenged newspaper headlines for satire, Gus Van Sant turned the camera toward television culture and let it indict itself. HAIRSPRAY (1988) was Waters’ move into the mainstream. Similarly, TO DIE FOR, would be Van Sant’s leap with a $20 million studio film. Van Sant would be the first of the New Queer Cinema filmmakers to be deemed profitable after his Portland Trilogy. At first glance, one might see TO DIE FOR as retreating from a political stance; however, Van Sant’s experiment with mainstream appeal is slathered with camp. Suzanne Stone is Suzanne Maretto’s drag name. In her world, life is a popularity contest and talent is optional. Daytime television had already proven that exposure was the new currency. Sally Jessy Raphael, Oprah, Ricki Lake, Phil Donahue. Courtroom drama became serialized entertainment, from the Menendez brothers to O.J., unfolding live alongside the rise of 24-hour news. An entire generation began mutating in real time, edging toward the lonely media obsession of Chip in THE CABLE GUY (1996). Suzanne has a dream. She will be a star. Nothing will obstruct that trajectory. Her ambition gives her authority, autonomy, and strength. When her husband Larry (Matt Dillan) decides she should scale back her dreams, even the teenagers in the film provide the answer: divorce him. To Suzanne, that would be failure. So, instead of separating from Larry, she recruits a trio of teens played by Joaquin Phoenix (still credited as Leaf), Casey Affleck, and Alison Folland, to commit murder. Adapted from Joyce Maynard’s novel, which was inspired by the Pamela Smart case, and sharpened by Buck Henry into acidic satire, the film examines ambition channeled entirely through the lens of exposure. At the film’s center is Nicole Kidman, then publicly framed as “Mrs. Tom Cruise.” Suzanne Stone offered something radical: the chance to weaponize her own image. Kidman attacked the role with rigorous preparation, arriving with notebooks, vocal drills, and scene breakdowns. Van Sant trusted her instincts and Kidman was like an assistant director on the film. On screen, she detonates the blonde bombshell stereotype from within. Her performance never stops; Suzanne is in permanent audition mode. Always reading from some imaginary TelePrompTer. “You’re not anybody in America unless you’re on TV,” Suzanne insists. Suzanne does not merely seek attention; her very moral compass is rewritten by the camera’s gaze. Her husband’s murder, her seductions, even her private rehearsals, all function as marketable content. She is both producer and product, performer and currency. We know this person today as an “Influencer.” Marriage becomes performance art. Local news becomes drag. Suzanne’s femininity is exaggerated to the point of camp, a hyper-feminine construct whose make-up palette always compliments the production design. While political mockumentaries gained an audience with Robert Altman’s series Tanner ‘88 and Tim Robbin’s BOB ROBERTS (1992), the structure Van Sant uses anticipates a future of YouTube videos, TikTok trends, and Instagram reels decades before ring lights and algorithmic validation. Lydia Mertz, Suzanne’s protégé, embodies early-’90s nihilism and delivers the film’s closing meditation on visibility and worth. In her attempt to deconstruct Suzanne’s mantra and take it to its absurdist end, she finds an irony she shrugs off. “What’s the point of doing anything worthwhile if there’s nobody watching? So when people are watching, it makes you a better person. So if everybody was on TV all the time, everybody would be better people. But if everybody was on TV all the time, there wouldn’t be anybody left to watch, and that’s where I get confused.” Suzanne’s belief that visibility equals existence, mirrors today’s metrics-driven culture. People as brands, leaving a lasting impression on culture itself. Van Sant gives Suzanne the immortality she desperately sought after, a face to be recognized forever. In an era where the self can be synthetically generated and endlessly optimized, Suzanne Stone would have been a perfect warning against narcissism; however we were too busy watching our impressive 24/7 news channels to worry about that. [Shaun Huhn]

---

Screening as part of the Cold Sweat double feature series, programmed in partnership with local screen printer Sarah Hamburger, who will have a limited selection of t-shirts for sale at the event.

Jean-Luc Godard's ALPHAVILLE (France)

Siskel Film Center – Friday, 6pm and Sunday, 3:30pm

The first maximalist film by the prolific director Jean-Luc Godard. While there are no Langian sets or blockbuster effects, Godard creates a science-fiction noir that pulls from both his earlier work and other films in the genre. Inspired by 20th-century pulp fiction, Godard asked audiences of his day to imagine a future technocratic dictatorship where technology kept emotional language away from members of society. This unsettling piece of alienation, coupled with sensual visuals, adds a unique flavor to Godard’s filmography; it's a step away from more intimate films like BREATHLESS (1960). Taking the camera around Paris of 1965, Godard pervades our vision with a futuristic gloom and plants us in the world of Lemmy Caution (played by Eddie Constantine, re-creating a role he'd played in multiple B noirs). Godard borrows genre tropes from noir and science fiction, incorporating key factors that audiences will immediately find recognizable. Yet as a notorious deconstructionist, he pulls the rug out from under the viewer by mixing his influences together until they become, simply, Godardian. Today, audiences still find ALPHAVILLE unique in its experimentation with genre conventions. As one expects from Godard, the director constantly plays with editing within scenes, reminding the viewer of the showman’s presence. Screening as part of the Lo-Fi Sci-Fi series. (1965, 99 mins, DCP Digital) [Ray Ebarb]

Éric Rohmer’s THE AVIATOR’S WIFE (France)

Doc Films (at the University of Chicago) – Saturday, 4pm

When you watch the films of Claude Chabrol, you can tell right away that he cowrote the first book-length critical study of Alfred Hitchcock. When you watch the films of that book’s co-author, Éric Rohmer… well, not so much. THE AVIATOR’S WIFE, however, is the exception that proves the rule, a movie that revisits some of Hitchcock’s favorite themes and motifs (doubling, surveillance, the limits of knowledge) and puts them in the service of a romantic comedy. François (Philippe Marlaud, who died in a tragic accident shortly after the film was released) is a young man of 20; he works nights at the post office and takes college classes by day. He’s also somehow involved with a beautiful 25-year-old named Anne (Marie Rivière, in the second of her four films with Rohmer). Anne had been involved with a married airline pilot, Christian, but shortly after the movie starts, he drops in on her to tell her his wife is pregnant and he has no intention of renewing the affair. Walking by, François sees Anne and Christian leave her building together just after Christian has broken things off. Like many a Hitchcock hero, François is left unaware of key developments that the director shares with the audience; he spends a good deal of the rest of THE AVIATOR’S WIFE snooping on Christian, hoping to get some dirt on him or at least find out if he’s still seeing Anne. While fumbling at his detective work, François catches the eye of a curious 15-year-old named Lucie, who strikes up a conversation with him and in moments decides to join him on his quest. If this were a Hitchcock movie, François and Lucie would likely fall in love over their mutual curiosity, but Rohmer has other things in mind for his characters. The film culminates with the reunion of François and Anne, who go through an emotionally messy encounter in her studio apartment that finds her doing most of the talking. This development—or rather, the autonomy and eloquence that Rohmer grants to Anne—marks a sharp turn away from the male-narrated Six Moral Tales that the director made in from the 1960s to the early 1970s. THE AVIATOR’S WIFE marked the beginning of Rohmer’s second series, called Comedies and Proverbs, that made up most of his 1980s output. For Dave Kehr, writing about the film in 1982, the difference between the two series lay in Rohmer’s shift to “a subjectivity that moves from one character to another, giving them all a greater degree of freedom, more room to improvise, more contradictory and complex humanity.” He added, “The five-year spacing of the ages, and the discrete psychological stages the four main characters fall into—Lucie’s open flirtatiousness, François’ moody romanticism, Anne’s uncertainty, and Christian’s newfound domesticity—suggest a very rigid kind of schematization. But there’s no trace of it in Rohmer’s superbly languorous understated direction. When there’s this much understanding of behavioral detail—the small, circuitous ways in which people move from point A to point B—the fixed, hard points of plot and structure no longer stand out; they’re subsumed by character.” Screening as part of the City Serendipity series. (1981, 106 min, DCP Digital) [Ben Sachs]

Agnès Varda's VAGABOND (France)

Doc Films (at the University of Chicago) – Thursday, 7pm

Not all who wander are lost, but it could equally be said that not all who wander wish to ever find or be found. Some are happy to be forever sans toit ni loi (the film's original French title)—without roof or law. Such is the case for Mona, the protagonist of Agnes Varda's staggeringly recusant VAGABOND. The aimless wanderer in question is played by a teenaged Sandrine Bonnaire; her greasy-haired, unwashed lack of naïveté brings a decidedly enigmatic element to the film's already elusive structure. The plot accounts for Mona's last weeks before she freezes to death in a ditch, with Varda employing a combination of narrative enactments and documentary-like interviews with those who encountered her before she died. A mysterious narrator voiced by Varda herself declares that no one claimed her body after she died, and that she seemed to emanate from the sea; Mona is then seen emerging naked from a cold ocean while two boys admire her from afar. Thus begins the film's overarching point of view, one in which the vagabond is little known and used only as a blank slate onto which her acquaintances project their own expectations and disappointments. Though it opens with Mona's death, the rest of the film is not at all hampered by the inter-film spoilers. She lived just as aimlessly as she died, and the details of her life weeks before her demise present another slate onto which viewers can project their hopes for the seemingly apathetic drifter. Varda's poetic filmmaking encourages the disconnect between the viewers and the characters, and even between the characters themselves. Slow tracking shots imitate a voyeuristic gaze and first-person interviews reveal some deceit among the fictional subjects. Even Varda's use of nonlinear structuring suggests such discord, as the confusion imitates Mona's mysteriousness. A string-heavy score betrays underlying anxiety, while music from The Doors and Les Rita Mitsouko highlight her rebellious nonchalance. The film's disarray comes together to present only one knowable fact about Mona: that no one really knew her at all. Screening as part of the Femalaise series. (1986, 105 min, DCP Digital) [Kat Sachs]

Alice Wu’s SAVING FACE (US)

Alamo Drafthouse – Sunday, 6:15pm and Monday, 4:15pm

After the onslaught of lesbian tragedies that dominated burgeoning queer cinema in the '90s, early oughts romantic comedies like KISSING JESSICA STEIN (2001), PUCCINI FOR BEGINNERS (2004), SAVING FACE (2005), and IMAGINE ME AND YOU (2005) brought a breath of fresh air to LGBTQ audiences. I remember watching each of these movies in theaters, feeling such joy alongside other audience members as we experienced happy endings and authentic depictions of lesbian romance on screen. The audience of SAVING FACE was especially receptive, and I remember waves of laughter, audible gasps, and roaring applause for the film. It clearly resonated with audiences over the two decades that followed release, despite not being a broad box office success. The success of SAVING FACE has much to do with the incredible sensitivity and levity that first-time director Alice Wu brought to her depiction of the challenges two women face in attempting a lesbian romance while honoring social norms in their Flushing, Queens, immigrant Chinese community. Wil (Michelle Krusiec), an ambitious surgeon and closeted lesbian, hides behind androgynous, drab clothes as her mother, Hwei-Lan (Joan Chen), attempts to set her up with an endless parade of unimpressive, respectable Chinese-American men. Vivian (Lynn Chen), a professional ballet dancer who is less closeted than Wil but still weighed down by a secret dream of pivoting to modern dance and abandoning the safer profession, is also dragged to weekly community matchmaking dinners in Flushing. When Wil and Vivian meet, sparks fly and they attempt a bumbling romance, chafed by the pressures and conservative norms inflicted by their strict Chinese parents. The plot thickens delightfully when Wil's very traditional (but single) mother reveals that she is pregnant and refuses to name the father. Suddenly both Wil and Hwei-Lan must navigate the shame of the patriarch of their family and learn to become roommates in a rather cramped Brooklyn apartment because Hwei-Lan has been expelled from her home. Joan Chen, whom many will recognize from her roles on Twin Peaks (1990-91) or in Bertolucci's THE LAST EMPEROR (1987), is utterly charming and silly as Hwei-Lan, portraying with a beautiful blend of levity and drama Hwei-Lan's difficulty navigating the societal values she adheres to while attempting to support her daughter. Director Alice Wu brings a deft touch to the characters and their growth throughout this film, showing that this tight-knit community is much more complex, loving, funny, and unique than it may appear to outsiders. Wu's screenwriting skill is evident in her ability to lighten the film without doing so at the expense of the conservative social values that the Flushing community adheres to. The only character of the film who falls somewhat flat is Wil's neighbor and friend, who is often used to provide comic relief and contrast as the only non-Chinese character in a scene, but does not convey the depth provided to other Asian supporting actors in the Wu's script. As this is a debut film, it’s not surprising to find this minor flaw, and truly, it is the only glaring flaw to me in this otherwise absolutely charming film. Alice Wu took many years off between directing SAVING FACE and her next feature film, THE HALF OF IT (2020), which was even more critically acclaimed and, I would argue, a pitch-perfect film. One hopes she won't make us wait too long to see her next foray. (2005, 91 min, DCP Digital) [Alex Ensign]

Maïlys Vallade and Liane-Cho Han’s LITTLE AMÉLIE OR THE CHARACTER OF RAIN (France/Belgium/Animation)

FACETS – Sunday, 11am

As of this writing, my child is sixteen months old, and though it’s highly unlikely I’ll ever know how he experiences the world, something like LITTLE AMÉLIE OR THE CHARACTER OF RAIN gives me a small glimpse into the prospect. Based on a semi-autobiographical novel by Amélie Nothomb, LITTLE AMÉLIE turns childhood growth into something less narrativized and more sensorial, the experience of absorbing the world around you becoming a monumental task in itself. The young Amélie, calling herself a “god” as she enters the world, is practically catatonic for the first two years of her life, an impenetrable bubble of stasis waiting for the world to literally shake her awake. She eventually learns to walk and talk with incredible speed, racing to catch up with her surroundings, both as an emerging member of the human species, as well as a Belgian catching up to the culture and nature of her family’s new Japanese environs. Amélie’s introspective journey is as much shaped by Belgian chocolate as it is koi fish, blooming spring flowers, and the literal calligraphy of her name in Japanese kanji—“Ame,” she learns, is the Japanese word for “rain.” The film’s animation style similarly works to dazzle with bright, evocative colors, the two-dimensional form bringing each new sensation to life through textured, shimmering hues. We, alongside Amélie, experience the world anew, with heartbreak and wonder sitting alongside each other. To take in the world is to experience humanity’s gloom and joy in tandem, the film teaches, and for something so profound to be discovered in a film geared toward young audiences feels like a gift for the taking. (2025, 78 min, DCP Digital) [Ben Kaye]

Jeff Kwitny's ICED (US)

Music Box Theatre – Friday, 11:45pm

Jeff Kwitny, who had a short career directing low-budget horror films before going on to write for cartoons like Animaniacs and Cow and Chicken in the ‘90s, wasn’t ever exactly a household name. But his most lasting film ICED was a solid enough calling card that raises some “what-ifs” about how he would have stretched his ingenuity beyond a limited setting, cast, and budget. The film’s plot can be loosely assumed if you throw “ski resort slasher” into the algorithm of your brain—a group of friends gather together at a ski resort several years after their hotheaded friend Jeff (Dan Smith) died in an accident on the slopes. The friends proceed to get targeted in their cabin by a malevolent skier in a blue jacket and broken visor who’s intent on picking them off one by one. As with most low-budget horror, the intrigue comes from what Kwitny and writer/actor Joseph Alan Johnson decide to do with the limited resources and storytelling palette provided by a slasher made well into the subgenre’s existence. By now the form was well established, and even though the micro-genre of Slasher Deconstruction hadn’t taken off as it would in the ‘90s, the slapdash nature with which ICED burns through tropes at the expense of a coherent narrative makes it a bit like a horror-formalist project, if by accident. The narrative machinations late in the film are both obvious and nonsensical, building backstory extremely late to resolve the narrative quickly, only to have a slasher-stinger that makes even less sense. But everything still flows smoothly, and Kwitny and Johnson build out their skeletal narrative frame with all kinds of marginal pleasures, weird details that stick out because of their eccentricity relative to the roteness of the surroundings, including marvelously campy line readings and the occasional cross-cutting to imagined softcore sex scenes. Lo-fi visual tricks like killer POV shots looking through a broken visor or the near-constant steam in outdoor shots provide some genuinely interesting images, and certain kills (in particular the first one where a character gets ground into pulp by a tractor in the snow, the aftermath of which is haunting in its gruesome simplicity) sing enough to carry the film through its more by-numbers plotting. There’s a breezy fun that’s hard to deny, even if viewers may be disappointed at how few of the deaths involve ice. (1989, 86 min, DCP Digital) [Maxwell Courtright]

---

Presented by SUPER-HORROR-RAMA!, who is also presenting the 1995 horror film FROSTBITER (85 min, DCP Digital) on Saturday at 11:45pm.

John Coney's SPACE IS THE PLACE (US)

Music Box Theatre – Saturday and Sunday, 11:30am

SPACE IS THE PLACE is a very odd film, written by and starring the brilliant composer/prophet from space Sun Ra. The main plot is basically that of Sun Ra's own reinvention as an interstellar prophet. He plays Sun Ra, who finds enlightenment on another planet and returns to Earth to save his African-American brethren from a supernatural pimp-overlord, using his music to spread his message. Ra intended it as a lighthearted homage to cheap 1950s science fiction, but a lengthy subplot involving pimps and sex workers clashed with Ra's scenes and placed it firmly in the Blaxploitation genre. Ra decided that these elements were unnecessary pandering that detracted from his message (and he was right), and for decades the film was available only in a shortened 63-minute version that stuck more closely to his vision. The suppressed footage was eventually restored for the 2003 DVD release. Genre digressions aside, SPACE IS THE PLACE is a unique creation, a foggy window into one of the most creative minds of the twentieth century: equal parts maddening and enlightening, off-putting in its sometimes-amateurish construction but hypnotizing nonetheless. Screening as part of the Brothers from Another Planet series. (1974, 85 min, DCP Digital) [Michael W. Phillips Jr.]

Hou Hsiao-Hsien's MILLENNIUM MAMBO (Taiwan)

Alamo Drafthouse – Sunday, 4pm

After its premiere at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival, Hou Hsiao-Hsien cut MILLENNIUM MAMBO by about 15 minutes, excising much of the subplot in which the young heroine, Vicky (Shu Qi), travels to northern Japan on a whim. This passage makes a great impression in the subsequent version, even though—or perhaps because—it seems so fleeting. The heroine registers the change in landscape enough to comment on it in her narration, but she doesn’t internalize it; maybe it’s a result of having felt so transient for so long. In any case, the Japanese visit doesn’t interrupt the film’s hypnotic flow, which is tied to both Vicky’s experience (as a passive, drug-addled raver in turn-of-the-millennium Taipei) and the techno music that drives the soundtrack. Hou’s perspective feels detached in MILLENNIUM MAMBO, despite the fact that he shoots much of the action in medium shot and frequently moves the camera to observe people in motion. That he and screenwriter Chu T’ien-wen have Vicky narrate the story from ten years in the future heightens one’s sense of distance. Adding a layer of mystery to the story, Vicky doesn’t divulge what she’s doing in 2011; one simply gathers that she’s a different person at this point and that she views her young adulthood with feelings of loss. Her experience as a young adult is certainly lamentable: a high school dropout, she moves to Taipei with her boyfriend Hao-Hao to immerse herself in the city’s rave scene. Hao-Hao is often high and abusive, driving Vicky to flee their tiny apartment and take solace with an older gangster named Jack (who may care for her, but doesn’t try to convince her to leave her boyfriend for good). She returns to Hao-Hao a few times, however, drawn to him by some mutual self-annihilating impulse. That impulse provides the film with its dark heart—it’s a movie about the desire to lose yourself and the emotional baggage you still can’t get rid of in the process. Screening as part of the Sad Girl Cinema Club. (2001, 101 min, DCP Digital) [Ben Sachs]

Hal Ashby's HAROLD AND MAUDE (US)

Alamo Drafthouse – Monday, 7pm

Hal Ashby’s second film, HAROLD AND MAUDE, is a morbid black comedy about finding one’s own happiness and what that means across generations. Harold (Bud Cort) is a disaffected young man living with his wealthy widowed mother who craves her attention, staging elaborately gruesome fake suicide scene, which she ignores. Harold also attends funeral of people he does not know. One day while attending one of these, he meets Maude (Ruth Gordon), a nearly 80-year-old woman with an unusually strong zest for life and wisdom to match her years. The two strike up an unlikely friendship that leads to more, as Harold learns there’s more to life than what he’s known in his hermetic world. Ashby’s film received mixed opinions upon its initial release but has aged well and gained a strong cult following in the years since thanks in part to its zany unpredictability, engaging performances by Gordon and Cort, and its bright, upbeat score performed by Cat Stevens. Harold’s moroseness and seeming death wish, the film’s exploration of mother-son relationships through Harold’s relationship with Maude, and the extent to which that reaches add a dark undercurrent to this film about coming of age and living life to the fullest. Screening as part of the Queer Film Theory 101 series. (1971, 91 min, DCP Digital) [Kyle Cubr]

James Foley's FEAR (US)

Alamo Drafthouse – Wednesday, 9:30pm

There’s something almost hypnotic about the way FEAR lulls you in. It masquerades as a teenage romance while hinting at something darker beneath its polished surface. James Foley, known for his exploration of desperate men (AT CLOSE RANGE, GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS), takes the well-worn girl-meets-boy narrative and warps it into something grotesque and uncomfortably real. At its core, FEAR is about control—who has it, who loses it, and who is willing to destroy everything to get it back. Reese Witherspoon’s Nicole, an innocent sixteen-year-old, is the daughter of Steve (William Petersen), a domineering father grappling with his own wounded masculinity. Enter Mark Wahlberg’s David, a bad boy with carefully curated sensitivity, a predator in heartthrob packaging. From his first appearance, David feels too good to be true, and Foley masterfully lets the audience linger on his charm long enough for it to sour. Wahlberg’s performance balances charm and menace with unsettling fluidity. David isn’t a caricature of evil; he’s the kind of person who might briefly convince you of his sincerity. His whispered promises are laced with control and his smile is just a touch too rehearsed. By the time he carves “Nicole 4 Eva” into his chest, he becomes a figure of pure terror. Wahlberg’s transition from Marky Mark to serious actor began with FEAR, as he embraced a role demanding both charisma and darkness. (There’s still a Marky Mark song on the soundtrack just in case.) Witherspoon matches him, portraying Nicole’s teenage defiance alongside a growing realization of her powerlessness. Foley builds tension meticulously, with the infamous roller coaster scene epitomizing the film’s blend of desire laced with danger and pleasure wrapped in control. The suburban setting, a Seattle suburb recreated in Vancouver, shifts from a symbol of safety to a suffocating trap. The early ‘90s grunge undercurrent, reflected in the soundtrack featuring Bush and other post-grunge acts, mirrors the film’s themes of rebellion and alienation while never feeling like a tie-in cash grab. When David and his gang invade Nicole’s home in the climactic act, it’s pure Peckinpah-lite—a suburban STRAW DOGS (1971) for the MTV generation. Petersen’s Steve Walker echoes Dustin Hoffman’s David Sumner in STRAW DOGS, both men attempting to shield their families through control, only to confront violence they’re unprepared for. While Hoffman’s intellectual passivity makes his transformation unsettling, Petersen embodies a quieter but equally flawed paternalism. The thematic parallels to STRAW DOGS—outsiders disrupting stability, toxic masculinity, and the home as a battleground—feel deliberate, but also reflect the lasting impact of Peckinpah’s film. Foley decided to strip away moral ambiguity found in STRAW DOGS. By the time you realize the boyfriend is actually a menace and not equal to Nicole’s father in demanding control of her agency, FEAR races toward its home invasion ending. There’s no question of whether David might be redeemed; there’s only the certainty that he must be destroyed. Proven further by the original ending that left David’s future up for interpretation. The script by Christopher Crowe was inspired by real-life stalking cases, especially the stalking and murder of Rebecca Schaeffer in 1989. Audiences at the time were not interested in an ominous ending where a stalker may move on to another pursuit, they wanted the wrong in the world put right. The supporting cast, including Alyssa Milano as Nicole’s best friend and Amy Brenneman as her stepmother, adds depth, showcasing how easily David’s charm ensnares those around him. FEAR has aged into a cult classic not for its originality but for its primal exploration of fear—of losing control, of being watched, owned, and consumed. Foley understood that his film wasn’t just about an obsessive boyfriend—it’s about the dangers lurking beneath desire, the way passion and terror can become indistinguishable when the wrong man whispers the right words. And more importantly, when the person you’re dating beats up your friends and gives you an “accidental” black eye, they should be tossed out a window. Screening as part of the Weird Wednesday series. (1996, 97 min, DCP Digital) [Shaun Huhn]

Martin Scorsese's THE AGE OF INNOCENCE (US)

The Davis Theater – Wednesday, 7pm

Depending on your point of view, this is either one of Martin Scorsese's grandest failures or one of his boldest triumphs. Certainly, it was unexpected for Scorsese to adapt Pulitzer Prize-winning Edith Wharton's novel, set among the high society of 1870s New York. Wharton's style is as reserved as the director's is visceral, and Scorsese approaches the discrepancy as a challenge: How to translate such a literary work, which derives its force from its describing unexpressed emotion, into a wholly cinematic one? Maintaining a placid tone in the performances, Scorsese pours himself into the dressing of the film: decor, positions of extras, music cues, verbose narration. One of the most obvious models here is Kubrick's BARRY LYNDON, a film that Scorsese ranks among his favorites, and it shares with that movie a curiously inverted relationship between surface emotion and dramaturgy. (Indeed, this often seems as much a response to Kubrick as it does to Wharton.) The story is of an illicit affair between the complacent Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis) and his wife's non-conformist cousin (Michelle Pfeiffer), a subject of barely hidden scorn since she walked out on a loveless marriage. Nearly all of the behavior we see is determined (hauntingly, tediously) by a rigid social order and the constant threat of excommunication; for this reason, Scorsese referred to AGE OF INNOCENCE as his most violent film. (1993, 139 min, DCP Digital) [Ben Sachs]

Jean Rollin's FASCINATION (France)

Alliance Française de Chicago – Monday, 6:30pm

The marriage of the erotic and the macabre becomes an inescapable force in Jean Rollin’s FASCINATION, a sensual nightmare of a movie. The longer we find ourselves trapped in the abandoned castle inhabited by temptresses Eva (Brigitte Lahaie) and Elisabeth (Franca Maï), the deeper we realize that the choice between fear and temptation has slowly become one and the same. It’s 1905, and the preening macho, Marc (Jean-Marie Lemaire), has succumbed to a greed that has pitted his den of thieves against him, leading to his hideaway in the aforementioned castle. His persistence in trying to tame Eva and Elisabeth—women far more interested in the love and lust they see in each other than anything Marc can offer them—builds to the point where, joined for a larger cabal of blood-hungry maidens, his doomed fate is practically written in stone. Rollin’s camera shifts between raw intimacy and stately observation, running up and down staircases to capture the madcap action before serenely and patiently sitting still, capturing the fantastical images at hand. Due to a series of financial disappointments in his filmmaking career, Rollin spent much of his later years making explicitly pornographic cinema, though works like FASCINATION make the case for the artistry that sensuality and sexuality play in the world of the moving image. It’s no wonder one of FASCINATION’s most iconic images remains Brigitte Lahaie wandering across a bridge, her nude body wearing a black cloak carrying a domineering scythe, her breast artfully escaping from underneath, that magical bond between death and desire perfectly captured onscreen. Screening as part of the February Fantastique Film Festival. Guests will enjoy a complimentary glass of wine and a post-screening discussion with Bram Stoker Award winning author John Everson. (1979, 80 min, Digital Projection) [Ben Kaye]

Coralie Fargeat's THE SUBSTANCE (France/US)

Alamo Drafthouse – Wednesday, 6:45pm

The newest film by French genre fiend Coralie Fargeat is body horror in extremis. In 2017 she gave us REVENGE, an over-the-top bloody pastiche of rape and revenge/one-(wo)man army exploitation films. A preposterously bloody affair to the point of almost being camp, REVENGE polarized its audiences. With THE SUBSTANCE, we see both the natural evolution and a giant leap in her filmmaking. A sci-fi horror, THE SUBSTANCE centers around Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), a 50-year-old media celebrity whose star has faded into being a TV aerobics host. After getting into a car accident, the nurse who is attending to her gives her a flash drive with an ad for “The Substance,” a mysterious cure-all guaranteed to make you perfect again. After some deliberation, Sparkle decides to partake. The film ratchets up into high-concept here as the serum creates a fully formed, younger, astonishingly beautiful woman that literally crawls out of Sparkle’s body like some kind of Cronenbergian Athena. This new Sparkle, Sue (Margaret Qualley) is both a physical and psychological manifestation of Sparkle that requires upkeep. Only one can be conscious at a time, and must switch back and forth every seven days in order to maintain stasis. But of course, they don't. Fargeat uses THE SUBSTANCE to talk about a lot of things at once: the psychological weight of aging (particularly as a woman), the entertainment industry, Ozempic, self-loathing, addiction. But while this movie is gross—and it's very gross—it's also decidedly campy and funny. It just received a Golden Globe nomination for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy, if that gives you an idea of how purposefully silly this movie is. There is a great balance between the unsettling and the humorous, and Fargeat knows exactly when to lean harder into which. While one could dismissively say this is a modern take on Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, it equally draws from such diverse films such as Brian Yunza’s SOCIETY (1989) for body horror social satire, Paul Verhoeven’s SHOWGIRLS (1995) for camp explorations of sex and sexuality, Darren Aronofky’s REQUIEM FOR A DREAM (2000) for the physical degradation of addiction, and of course David Cronenerg’s THE FLY (1988) for, well, watching a human body fall apart in real time. By far greater than the sum of those parts, THE SUBSTANCE gives us something like Katheryn Bigelow’s POINT BREAK (1991), a film that can be enjoyed on multiple levels as either pure, mindlessly indulgent genre entertainment, or as an acerbically sharp commentary. It's a rare film that is as clever and smart as it is completely disgusting. Somehow this movie has found an audience in both the arthouse and grindhouse, with both the credentialed critics and the gutterstink gorehounds. When Ovidio G. Assonitis and Roberto Piazzoli released BEYOND THE DOOR (1974), the legally adjudicated Italian rip off of THE EXORCIST (1973), they infamously hired people to pretend to pass out during screenings and have ambulances waiting outside movie theatres in order to drum up hype for the film. Two months ago, as I was at the movies seeing a different film, someone in the next theatre actually threw up, passed out, and took a ride in an ambulance out of a screening of THE SUBSTANCE. Proof that for 50 years that the film industry has been trying to fake what THE SUBSTANCE naturally has. (2024, 141 min, DCP Digital) [Raphael Jose Martinez]

Martin Scorsese's RAGING BULL (US)

Doc Films (at the University of Chicago) – Saturday, 9pm

Trapped in a hospital bed, Martin Scorsese was at death’s door. After years of pushing his body through intense working hours, prescription drug abuse, and sacrilegious amounts of cocaine, the then-35-year-old suffered internal bleeding, boarding brain hemorrhaging. Years prior, Robert De Niro was handed Raging Bull, the memoir of one-time middleweight champion boxer Jake LaMotta. Notorious for letting opponents pulverize his body into a numb chunk of meat to the point of exhaustion, LaMotta drank heavily, beat his wives, and racked up a charge for allowing the prostitution of a 14-year-old girl at his club. By the release of his book, he was an out-of-shape entertainer with brain damage working rundown night clubs to feed himself, reciting Shakespeare and cracking Don Rickles-esque crowd work. Seeing Jake’s potential as a character, De Niro pitched the story to Marty. Occupied by his promising follow-up to TAXI DRIVER (1976), Scorsese was deep into production planning for a nostalgic musical revue, NEW YORK, NEW YORK (1977), convinced he'd secure his spot as one of the great American directors. Navigating a turbulent marriage and an affair with his lead actor, Liza Minelli, there was no time for others’ passion projects; besides, he had no interest in a sports movie, with little exposure to boxing growing up. DeNiro would persist over the next few years. When the musical was a critical and financial disaster, Scorsese could not believe it, having given his all. Pushing closer to the edge, Marty had a revolving door of girlfriends and drug habits. In 1978, he was taken to the emergency room for coughing up blood and collapsed at 109 pounds. Watching the tubes keeping him alive coming in and out of his body, he saw how far he’d fallen from the son of two garment workers in Little Italy, a boy who had fallen under the influence of a charismatic priest and at one point considered becoming a seminarian. He recounts, “I prayed. But if I prayed, it was just to get through those 10 days and nights. I felt [if I was saved] it was for some reason. And even if it wasn’t for a reason, I had to make good use of it.’” He realized his self-destructive tendencies could bring anguish to anyone in his orbit, including those he loved, just like LaMotta. Finally, the director was ready. De Niro and Scorsese began putting a draft together from LaMotta’s text, then they brought Paul Schrader to work on a draft. After Schrader handed in his work in under six weeks, Scorsese and DeNiro put their finishing touches on Schrader’s structure, adding their favorite scenes from the memoir. The studio’s first reaction was, “Why would you want to tell a story about a human cockroach?” The preproduction research for both director and actor serves as a template for contemporary filmmakers and actors. De Niro’s preparation for the role inspired an entire generation of actors looking to commit their entire body, a standard that has become its own acting school. Scorsese and designers attended boxing matches, studied boxing photography books for composition, consulted LaMotta and his former trainers for accuracy, and home movies for the family’s interpersonal relationships. Having lost a fight, De Niro’s Jake mutters, “I’ve done a lot of bad things, Joey. Maybe it’s coming back to me.” After dancing with death, Scorsese worked on RAGING BULL as if it were the last film he’d ever make. Borrowing from the great masters, he weaves the most graceful brutality of the latter 20th century put to celluloid. Hitchcock’s PSYCHO (1960) shower sequence served as template for Jake’s annihilation on the robes, followed by a shot of Ray’s glove taken from Samuel Fuller’s THE STEEL HELMET (1951). One of the first boxing films of the sound era to place the camera inside the ring, director of photography Michael Chapman (TAXI DRIVER, THE LAST WALTZ and AMERICAN BOY) and Scorsese play with frame rates within takes, flying the camera through the action, and relishing in all they have at their disposal. To add an extra layer to the period piece, the production chose black and white film stock. The great Thelma Schoonmaker cut the film; this was her first feature as editor. Together with the director, she elevated the work to a vicious level of grit violence. Famously, when asked how such a nice lady could edit such violent films (for Scorsese), she replied, “Ah, but they aren’t violent until I’ve edited them.” In all its barbarity and beauty, the film gives a naked depiction of humanity. It delivers a vision as complex as its subject. To call RAGING BULL one of the greatest movies of the 1980s is a misnomer. The level of experimentation and personal filmmaking could only fit in the realm of 1970s New Hollywood. Along with THE KING OF COMEDY (1982), LaMotta’s story received a greenlight during a golden age of American cinema, only to release during the postmortem of United Artists and the cinematic wasteland of studios. Artists’ work is often cited as therapeutic. RAGING BULL offers a new light, proving that it can also be the first step towards repentance of sins. As the film is viewed for a 4K restoration, we should keep in mind how much the director has accomplished over the years. In the decades since the film’s release, Scorsese has continued to uplift new voices in cinema through the World Cinema Project and educate through the Film Foundation. The now-80-year-old director has made it clear his penance for his early years is permanent. Screening as part of the Screen Play: Cinematic Visions of Video Games and Sports series. (1980, 129 min, DCP Digital) [Ray Ebarb]

Jean-Luc Godard’s HAIL MARY (France/Switzerland/UK)

Doc Films (at the University of Chicago) – Sunday, 1:30pm

HAIL MARY was personally condemned by Pope John Paul II, and Jean-Luc Godard made a point of noting this in the film’s ad campaign; however, both the condemnation and Godard’s cheeky response seem out of keeping with the film itself, which is one of the director’s most probing and sincere works. HAIL MARY imagines an immaculate conception taking place in contemporary western Europe, with the mother being a relatively ordinary adolescent. Godard’s Marie is a young woman of roughly 18; her parents own a gas station, her boyfriend Joseph drives a taxi, and she plays on her high school basketball team. One day, Marie receives divine signal that she’s pregnant, even though she’s barely allowed Joseph (or any other man) to touch her. Godard depicts her epiphany in modernist fashion, shifting from Marie to the sound and then image of an airplane taking off, then following that with a breathtaking shot of a sunset accompanied by a blast of symphonic music (the score consists of excerpts from Bach and Dvořák). As with much of the filmmaker’s post-‘70s work, HAIL MARY shows Godard finely attuned to the beauty of the natural world; the frequent cutaways to lakes and skies invoke the serenity of Creation, which stands in contrast to the violence of Marie’s internal transformation. Godard’s depiction of the latter is what got the film in hot water, as Marie is often nude when she contemplates her soul and her desire to break free of her corporeal form. Yet these scenes would strike only the most reactionary viewer as pornographic. Like in PASSION (1982), Godard is striving to connect cinema with the enduring beauty of classic paintings, many of which consider the human form in the nude. He’s also dealing with the very nature of having a body, as distinct from having a soul. HAIL MARY amounts to a rather personal exploration of Christian morals in particular and religious faith in general, with many of the conversations revolving around whether other characters can believe that Marie is pregnant and still a virgin. “The cinema, like Christianity, isn’t founded on historical truth. It gives us one account of the story and asks us to believe it,” Godard later said in HISTOIRE(S) DU CINÉMA, and HAIL MARY marks a serious exploration of what it means to live with such unwavering belief. Preceded by Anne-Marie Miéville’s 1985 short film THE BOOK OF MARY (28 min, DCP Digital). (1985, 79 min, DCP Digital) [Ben Sachs]

Ugo Bienvenu's ARCO (France/Animation)

FACETS – Saturday, 3pm and 5pm

Two lonely kids form a life-changing bond across space and time. It’s a familiar premise in children’s media (one that finds a variation in another four-letter 2025 animated sci-fi film named after its protagonist, Pixar’s lovely ELIO), but ARCO has enough idiosyncratic details and artistry to stand out. In some faraway future in which climate disasters have forced humanity to live on self-sustaining platforms in the clouds, young Arco longs for escape. Specifically, he wants to travel through time like the rest of his family, whose mode of transportation is rainbows. Disobeying their rules (children cannot rainbow time travel before the age of 12), Arco takes to the sky and ends up (literally) crashing down back in 2075. Unable to return to his reality, he befriends Iris, a budding artist raised by a robot nanny in lieu of her perpetually-away parents, who show up at the dinner table as holograms beaming in from work. Tailed by a trio of bumbling conspiracy theorists and imperiled by the effects of climate change, the kids seek to find Arco a way home. With his co-writer Félix de Givry, Ugo Bienvenu creates a bittersweet story of foundational childhood friendship subtly set within a larger portrait of societal anomie. Neither Arco’s time, with its isolated homes perched high above an uninhabitable Earth, nor Iris’, with its substitution of AI for human labor, offer reassuring views of our planet’s future. While it’s not clear how one reality grew into the other (one of many world-building mysteries audiences might find intriguing or frustratingly vague), what is clear is that ARCO sees a world of endangerment where hope rests in the younger generations and their ingenuity, reflected in Iris’ ability to imagine things through drawing. Her bright artistic sensibility is embodied by the film, which bursts with literal rainbows of color and contains a gorgeous score by Arnaud Toulon. Without being precious about it, ARCO self-reflexively celebrates its own handmade form—let’s just call it Art—as a way forward for humankind. The version being screened is dubbed in English from the original French; while I admired the clever layering of Natalie Portman and Mark Ruffalo’s voices as the nanny robot Mikki, I was more skeptical of the contributions from Will Ferrell, Andy Samberg, and Flea, as well as the child voice actors. (2025, 89 min, DCP Digital) [Jonathan Leithold-Patt]

Kleber Mendonça Filho’s THE SECRET AGENT (Brazil)

FACETS – Sunday, 6pm

The films of Kleber Mendonça Filho unfold like novels, immersing viewers in the specificities of place while gradually revealing aspects of the principal characters that aren’t immediately apparent. They also abound in digressions and supporting characters, neither of which advance the plot so much as expand on it so that the world of the movie seems as rich as the one we inhabit. The richness of THE SECRET AGENT has a lot to do with how the film engages with Brazilian history. Mendonça Filho doesn’t confront the legacy of his nation’s military dictatorship head-on, but rather obliquely and circuitously, dramatizing how citizens lived under the terror of the period until that terror enters the foreground of the action. The story takes place mainly in 1977, at the height of the dictatorship; per a title card that comes near the beginning, this is a time of “great mischief,” one of several euphemisms for state-sponsored violence that arise during the film. Wagner Moura stars as a technical analyst who returns to his hometown of Recife after an unspecified time away. He wants to reconnect with his young son, who’s currently living with his maternal grandparents, but circumstances (also unspecified) keep the two from residing together. Mendonça Filho evokes a climate of fear and secrecy through his presentation of the intricate community networks that Moura’s character must navigate to stay safe in Recife. The writer-director also sometimes jumps forward a few decades to consider some young women in the present who are researching the character’s life, suggesting that Brazil is far from done with its culture of surveillance. These flash-forwards aren’t the only curveballs in THE SECRET AGENT, which also features a fascinating subplot about a human leg found in the body of a shark that’s washed up on the Recife coast (an event that coincides with the local popularity of JAWS) as well as a thorough account of how Recife’s police department functioned under dictatorship. The sheer volume of narrative detail recalls the films of Arnaud Desplechin, and Mendonça Filho adds to the complexity with his inspired direction, employing innovative widescreen compositions, unpredictable montage, and daring shifts in tone. Indeed, the film’s technical brilliance is so astonishing as to almost distract from the story, which is another way of saying that this towering achievement probably requires multiple viewings to reveal all it has to offer. (2025, 160 min, DCP Digital) [Ben Sachs]

Park Chan-wook's NO OTHER CHOICE (South Korea)

Doc Films (at the University of Chicago) – Saturday, 6pm

FACETS – Saturday, 7pm

Neon, the distribution company handling the US release of NO OTHER CHOICE, put out an exquisite piece of PR: “On behalf of Director Park Chan-wook's new film, we are cordially inviting all Fortune 500 CEOs to a special screening of NO OTHER CHOICE. This is truly a film that speaks to our gracious executive leaders and the culture they have cultivated.” Whether any CEO accepted the invitation is beside the point—the provocation lands cleanly. NO OTHER CHOICE looks directly at the class that treats labor as an abstraction and asks them to sit with the human residue left behind. Audiences have embraced the film for its sharp wit and plainspoken clarity, recognizing themselves in its vision as the world lurches each day closer toward economic collapse. The film follows Man-su (Lee Byung-hun), a veteran paper-industry professional whose stable life implodes after an abrupt layoff during corporate restructuring. What unfolds is a slow erosion marked by repetitive job interviews leading nowhere, mounting debts, and quiet domestic compromises. Months stretch into a year. Man-su’s sense of dignity becomes increasingly bound to professional reinstatement, and his family home, formerly a symbol of personal history and stability, becomes a pressure cooker. Park shapes Man-su’s moral descent with procedural discipline. Routine governs the rhythm. Each decision emerges through deliberation, framed as practical problem-solving rather than impulse. Park’s labyrinthine tales of vengeance like LADY VENGEANCE (2005) are traded here for a straightforward logic. The tension at each moral quandary comes from recognition. Every step makes sense. And morality becomes another variable to manage. This framework traces back to Donald E. Westlake’s 1997 novel The Ax, a corporate satire that charts violence as career strategy. Park retains the architecture while reshaping the emotional terrain. Man-su is no longer alone inside his reasoning like the novel’s protagonist Burke Devore. The film places him within a family whose survival depends on shared silence and mutual implication. Responsibility spreads outward. Consequences echo inward. Glimpses of other laid-off workers provide a mirror for Man-su: men who have given up, workers who have been spit out and forgotten. Within Park’s body of work, NO OTHER CHOICE occupies a transitional space. His precision remains unmistakable: calibrated compositions, ironic musical cues, an enduring fascination with self-justifying ethics. Yet the film abandons the operatic violence of his other films like OLDBOY (2003), THIRST (2009), and THE HANDMAIDEN (2016). Violence here feels laborious and draining. Murder aligns with job hunting, interviews, and evaluations. It becomes another task to complete, another box to check. Dark humor, awkward missteps, and poorly executed plans brush against slapstick, an unexpected lightness that keeps Man-su recognizably human. By shifting focus away from revenge and obsession toward systemic design, NO OTHER CHOICE emerges as Park Chan-wook’s most direct examination of work as ideology. Employment defines dignity. Automation signals erasure. Survival demands compromise. The film offers no relief, only a clear-eyed portrait of a system accelerating toward collapse, guided by those insulated from its costs. Build identity around labor, strip it away, demand adaptation, and call it opportunity. Eventually, resistance becomes inevitable. There is no other choice. Unless, of course, a few CEOs attended the premiere and decided to reduce profits and expand their workforce. Cinema inspires miracles all the time; maybe that’s why the film was released on Christmas day. (2025, 139 min, DCP Digital) [Shaun Huhn]

Todd Haynes' SAFE (US)

Music Box Theatre – Sunday and Monday, 9:30pm

Director Todd Haynes has restless eyes and ears that never linger in one aesthetic or time-period for longer than a film. And despite his continual shifts, it's the aesthetic that tends to star in his films, but this is never a shallow engagement. If Haynes can be said to have a formula, it is to find a pristine surface and scratch until we can see the uneasy construction underneath. His first (banned) public experiment was SUPERSTAR: THE KAREN CARPENTER STORY, in which he used Barbie doll whittling as an inspired, literal representation of Karen Carpenter's struggle with her eating disorder. FAR FROM HEAVEN honored and interrogated the world of Douglas Sirk. In I'M NOT THERE, he chipped away at the impenetrable image of Bob Dylan, all the while pointing at the impossibility of his project with a graphic mix of sympathy and irony. SAFE takes a break from public images to get intimate with a housewife's health. Shot and lit with the peachy haloes of a douche commercial, SAFE's blurry suburban Los Angeles is an unlikely venue for horror. We follow Carol White on her errands, to her exercise classes, with her friendly acquaintances; no one seems to mean her any harm. But it's precisely this vagueness—of purpose, of symptoms, of identity—that begins to gnaw at Carol until she is reduced to her flintiest self-preservation impulse. She suffers from both the controversial Multiple Chemical Sensitivity and the middle-class affliction of Unlimited Healing Budget, and either condition could prove fatal. Haynes takes care not to fix any problems or to answer stupid questions; the ending lingers in one's mind like an unresolved chord. Introduced by Grelley Duvall. (1995, 119 min, New 4K DCP Digital Restoration) [Josephine Ferorelli]

📽️ ALSO SCREENING

⚫ Alamo Drafthouse

Jess Franco’s 1974 film THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MIRROR (100 min, Digital Projection) screens Tuesday, 9:30pm, as part of the Terror Tuesday series. More here.

⚫ Chicago Cultural Center

Chicago Asian Pop-Up Cinema presents Yang Li’s 2024 film ESCAPE FROM THE 21ST CENTURY (98 min, Digital Projection) on Saturday at 11am. Free admission with RSVP. More info here.

⚫ Chicago Public Library

View all screenings taking place at Chicago Public Library branches here.

⚫ Cinema/Chicago

Digging Deeper Into Movies with Nick Davis, for which this edition’s theme is “Oscar Spotlight: What a Difference a Director Makes,” takes place Saturday from 11am to 12:30pm at the Alliance Française de Chicago (810 N. Dearborn St.). More info here.

⚫ Conversations at the Edge at the Siskel Film Center

Kioto Aoki: Findings (2013-2026), a program of 16mm films and a new 35mm slide work by the Chicago-based filmmaker, photographer, and musician, screens Thursday at 6pm with live musical score. Aoki will be in attendance for a postshow discussion and Q&A. More info here.

⚫ The Davis Theater

Terror Vision presents Thomas DeWier’s 1988 film DEATH BY DIALOGUE (89 min, Digital Projection) on Monday at 7pm. Free admission. More info here.

⚫ Doc Films (at the University of Chicago)

Wai Ka-fai’s 1997 film TOO MANY WAYS TO BE NO. 1 (90 min, 35mm) screens Friday, 7pm, as part of the Revolution of Their Time: 30 Years of Milkyway Image series.

Boris Barnet’s 1957 film THE WRESTLER AND THE CLOWN (95 min, 35mm) screens Sunday, 4pm, as part of the Boris Barnet: A Cinema Despite Life series.

Kioto Aoki and Cameron Worden’s UNTIME (ANNIHILATE THIS WEEK) (45 min, 35mm slides), “a multi-image work made for several 35mm slide projectors with no shutter or intermittent, operated in real time and accompanied by live music,” takes place Sunday, 7pm, along with screenings of Worden’s short films TODAY (IN A HAZE) and DIGITAL DEVIL SAGA.

Anne-Marie Miéville’s 1994 film LOU DIDN’T SAY NO (80 min, DCP Digital) screens Tuesday, 7pm, as part of the Anne-Marie Miéville: Not Reconciled series.

Boris Barnet’s 1947 film SECRET AGENT (88 min, 35mm) screens Wednesday, 7pm, as part of the Boris Barnet: A Cinema Despite Life series. Boris Barnet's 1931 film THE THAW (65 min, Digital Projection) will now screen Wednesday, 7pm, as part of the Boris Barnet: A Cinema Despite Life series. SECRET AGENT will screen Thursday, March 5 at 7pm.

Gurinder Chadha’s 2002 film BEND IT LIKE BECKHAM (112 min, 35mm) screens Thursday, 9:30pm, as part of the Screen Play: Cinematic Visions of Video Games and Sports series. More info on all screenings here.

⚫ FACETS

Tyler Michael Balantine presents…Sunday’s Best with Short Films by jellystone robinson on Sunday, 2pm, followed by a Q&A with robinson and a reception with food in the studio.

The Chicago Reel Film Club presents the 2023 film UNDERDOG (103 min, DCP Digital) on Tuesday at 7pm, preceded by a reception at 6pm. More info on this screening here. More info on all other screenings here.

⚫ Goethe-Institut Chicago (150 N. Michigan Ave., Suite 420)

Dagmar Schultz’s 2012 documentary AUDRE LORDE: THE BERLIN YEARS 1984-1992 (79 min, Digital Projection) screens Tuesday at 6pm. Free admission with registration. More info here.

⚫ Music Box Theatre

The 2026 Oscar Nominated Animated Short Films and Oscar Nominated Live Action Short Films begin screening, and Matt Johnson’s 2025 film NIRVANNA THE BAND THE SHOW THE MOVIE (95 min, DCP Digital) continues. See Venue website for showtimes.

Stephen Norrington’s 1998 film BLADE (120 min, 35mm) screens Friday and Saturday at midnight and Monday at 2pm, as part of the Brothers from Another Planet series.